In Ho Chi Minh City’s battle with floods, will dropping a 41-km-long concrete wall into the sea actually help or will it perpetuate a legacy of failed land-use policies and infrastructure miss-management that is largely responsible for accelerating inundation, damages and human misery? This is Part 1 of Mekong Eye’s investigation into the HCMC’s Vung Tau – Go Cong Sea Dyke project. Part 2, “Beware the Dyke—Responding to the root causes of flooding in Ho Chi Minh City” can be viewed here.

Spreading atop the Saigon River delta where it meets the Mekong Delta, Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) has always had to contend with flooding. Whether swollen rivers making their way to the sea or the sea’s high tides forcing their way inland, with half of HCMC’s land no higher than a meter above the average level of the sea, inundation has been a given.

Instead of methodically working within these natural constraints, the city’s stewards have seemingly taken to the reverse. They’ve allowed development to be led by investors seeking to profit from cheap, low-lying land that instead should be left open for flood reserves. They’ve been remiss in maintaining and expanding the city’s drainage infrastructure and even allowed development to fill in existing canals. They’ve been slow to regulate groundwater depletion, causing some areas of the city to sink at nearly 2cm per year. And they’ve not at all kept up with wastewater management needs, causing the city’s sewage to increasingly mix with flood waters.

Then there’s climate change. Vietnam is among nine countries where at least 50 million people will be impacted. Many of those are already residing in HCMC. With the nearby sea expected to rise one meter by 2100 and storms expected to intensify bringing with them both higher tidal storm surges and greater precipitation volumes, the municipality’s flooding challenges are accelerating. All of this was highlighted during a special release in Hanoi last month of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s new report on the potential impacts of a 1.5C rise in global temperatures.

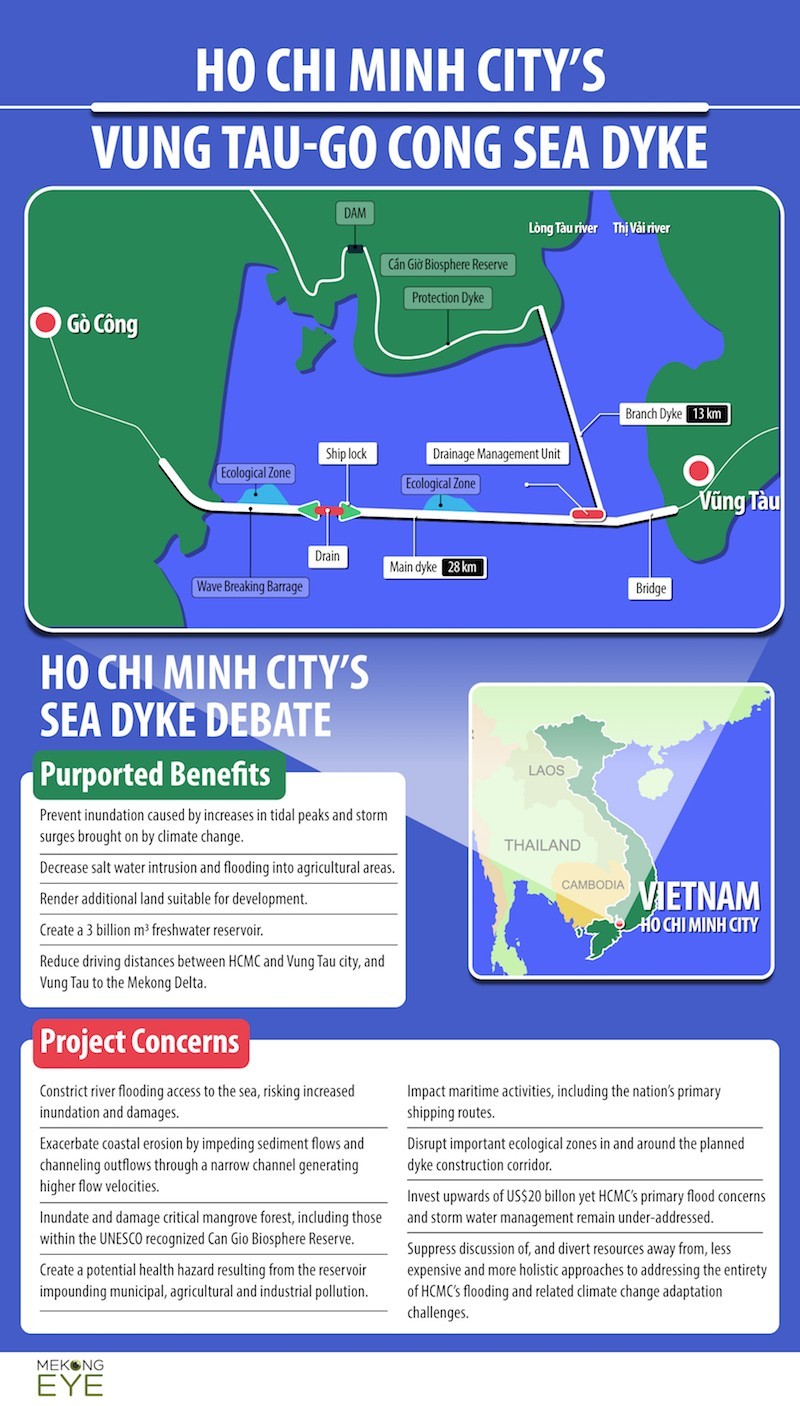

So after years of collecting dust, Vietnamese authorities are resurrecting a plan to construct a 25m-wide sea wall that they hope can fend off tidal floods and impede saltwater intrusion and water-logging for a 10,000 square kilometer area anchored by HCMC.

Operationally, the proposed Vung Tau – Go Cong Sea Dyke will also help to create a freshwater reservoir spanning 430 square kilometers and impounding up to 3 billion cubic meters of fresh water 40 kilometers southeast of HCMC. Containing this water will require constructing a dam and another 60 kilometers of barriers that will bisect the UNESCO-recognized Can Gio biosphere reserve.

The project will also require a number of sluice gates, a commercial shipping lock, and a 2,000m-wide drainage channel. An access bridge is also planned to enable the massive dyke to serve as a highway to reduce transporting time between HCMC and the coastal city of Vung Tau, and Vung Tau to the Mekong Delta.

Technical Risks and Operational Uncertainties

With the dyke’s resurrection has come amplification of longstanding criticisms. Fundamentally, experts argue that Vietnam is betting too much on 20th-century, large-scale infrastructure approaches they hope will control nature, when globally the trend is to work more holistically with nature. Moreover, they contend the dyke’s construction will cause environmental, economic and social damage.

Ho Long Phi, former director of the Center of Water Management and Climate Change (WACC), a branch of HCMC’s National University, argues that it is impossible for the dyke to fully protect the city. He points out that presently, even when tidal peaks are below one meter, rainy days generate standing water across the city. While the proposed dyke might reduce peak tide inflows, its operations will cause the low tides progressing toward the city to be higher than under natural conditions, and as a result, there will be less of an elevation buffer before inundation starts to occur.

Irrigation expert Nguyen Ngoc Anh expresses his concerns about the importance for the sea dyke to also efficiently evacuate water away from communities when rivers are rising and the rain is falling. He is particularly concentred that if the Dong Nai River and Mekong River are in flood at the same time, water releases though the dyke will be insufficient.

Prof. Nguyen An Nien, Chairman of HCMC Irrigation Science Association, former director of Vietnam Academy of Water Resources, worries about the impacts such a dyke will have on the southern coastal foundation, which has been shaped over more than one thousand years through the interaction between the neighboring Mekong and Dong Nai River systems. The Vung Tau – Go Cong Sea Dyke will block the mouth of Dong Nai River accelerating coastal erosion and alluvium shortages. This is especially troublesome now he says, as alluvium flows from the Mekong River have dropped 40 percent since upstream dams started operating and sand mining has increased.

“Whenever its drainage gate opens, the water can flow up to a speed of 6m/s which is too high for preventing downstream area from soil erosion,” Prof. Nguyen An Nien states.

There’s also fear that the reservoir will become a wastewater retention tank, where previously outflows from the Dong Nai River Basin and a part of the Mekong Delta flowed freely. Wastewater from households and industrial zones in HCMC, Bien Hoa, Binh Duong and Tan An will flow into the new freshwater lake. South Korea’s ten-year old Saemangeum Seawall has experienced pollution problems detrimental to wildlife. Other reclamation projects, including the project between Baltic Sea and Neva River, had to be postponed due to such environmental challenges.

In the opinion of Vu Hai, an engineer with over 50 years’ work experience in the sector of irrigation and construction and also a former lecturer of Hanoi University of Technology and Hanoi University of Civil Engineering, the project will increase water pollution of Ganh Rai bay and clearing costs of canals, as well as limit fish migration for breeding, which may drop fish quantity.

With five major and three smaller seaports to be impacted, the potential disruption of Vietnam’s most vibrant maritime economy is also a concern. Ships in excess of 2000,000 tons currently travel three separate routes toward the various ports, but the project will require them all to travel through a single lock. Nguyen Ngoc Anh questions whether even ten big ships would be able to pass through the dyke in a single day.

Prof. Dao Xuan Hoc notes that Dutch experts who have advised Vietnam on flood management have also warned of the extreme complexity associated with operating this kind of “super dyke” given the duel challenge of regulating both advancing tides and flooding rivers, along with the anticipated environmental and transportation challenges within a country with a lack of management experience.

Uprooting nature’s tidal control with concrete

Stretching from the coastal area of Dong Nai province to Long An province, Can Gio mangrove forest acts as a shield to mitigate sea level rise and to prevent inland areas from storms, winds, rising temperature and erosion. The ecosystem also helps to treat and filter water. These functions have caused the area to be referred to as HGMC’s green lung.

Dr. Le Xuan Tuan, with Hanoi University of Environment and Natural Resources, says the dyke will seriously damage key parts of the Can Gio Mangrove Biosphere Reserve. Instead, Tuan recommends, undertaking more research to evaluate the dyke’s impacts to the regional ecosystem with the aim to conserve the environment and environmental services within the Dong Nai – Sai Gon river basin.

Bureaucracy overstepping Science

Experts stress that the not only is the proposed US$3.3 billion cost for the project a lot for the country to absorb, but it’s a gross underestimation of those costs. They say the amount is only enough for basic infrastructure, and that US$20 billion will actually be needed for the dyke system to be fully operational. Furthermore, proponents claim that the state may only need to support 10-15 percent of the budget, with other private investors providing the balance, even though the project will lack any significant income generation.

In 2008, Trung Nam Cooperation was chosen to implement a US$440 million flood control project for HCMC that was to involve four dams. It has been delayed and there has been no announcement as to when funds will be dispersed. This project is part of the larger US$3 billion HCMC Flood Control Master Plan (Plan 1547). It’s now thought that the entire plan will be scrapped in lieu of growing momentum to build the sea dyke.

“We recommend stopping the Vung Tau – Go Cong Sea Dyke. If this project is approved, Plan 1547 will become useless. There is no reason to waste money for doing two projects with the same target,” Vu Hai advised.

The decision-making surrounding the sea dyke has been controversial. Its origins date back eight years to a visit to South Korea made by Prof. Dao Xuan Hoc, now Chairman of the Vietnam Irrigation Association, where he toured the then, just-completed, Saemangeum Seawall project. Upon his return, he worked with other experts to develop a proposal to secure US$1.4 million for a pre-feasibility study, which was sent directly to the Prime Minister. Criticisms was almost immediate, both because he bypassed the typical ministerial review process before submitting the proposal and for not seeking the opinions of independent experts. It’s even thought that a major motivation of project proponents is for the Irrigation Department and its experts to gain control of a four percent fee associated with the overall project costs that is to be allocated for their work on a feasibility study.

For the time being, however, the Ministry of Science and Technology has indeed launched six independent scientific research projects at the state level to examine the merits of the project. As pointed out in part 2 of this investigation, however, such a strong emphasis on the dyke itself presents a major barrier to HCMC actually resolving its flood management problems.

Part 2: Beware the Dyke—Responding to the root causes of flooding in Ho Chi Minh City

Story in Vietnamese Language Đâu là nguyên nhân thất bại của việc chống ngập ở TP.HCM?