An obscure fishing community longtime hidden from world view is now playing host to the single largest infrastructure project in Southeast Asia.

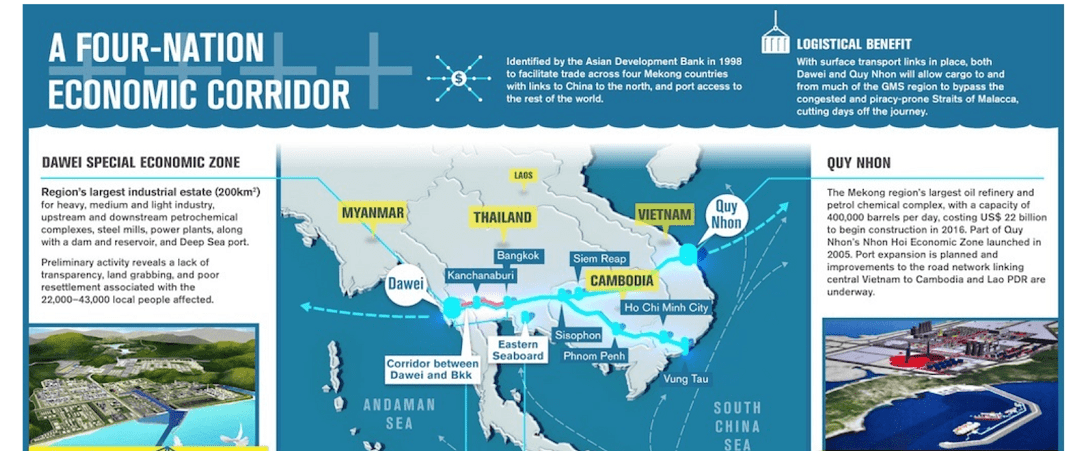

Some 196 square kilometers along Myanmar’s west coast is slated for transformation into a deep sea port and industrial estate unrivaled anywhere else in the region – and with trade and transport links reaching across Southeast Asia.

The nearest town, Dawei, from which the project draws its name, was previously a stronghold for the Karen National Union (KNU), during what was one of the world’s longest-running ethnic insurgencies. But a ceasefire and landmine clearing in the wake of Myanmar’s dawning democracy and market economy has enticed neighboring Thai investors.

Located just 350 km west of the Bangkok, Dawei represents an attractive location for industrial expansion due to abundant natural resources, lower land, labor and regulatory costs. Moreover, port facilities at Dawei would save Thai traders at least three days in transit time by eliminating sea passage through the Gulf of Thailand and the congested and troubled Straits of Malacca.

Burmese fishermen prepare their nets before a voyage near the planned Dawei SEZ in Bawar Village, Burma. (Photo by Taylor Weidman/Getty Images)

The rough road to Dawei

In 2008 one of Thailand’s leading infrastructure construction companies, Italian-Thai Development (ITD), launched plans for Dawei’s transformation. With cooperation from the Myanmar government, the Dawei Special Economic Zone (DSEZ) was announced. The project would span an area nearly the size of Vietnam’s capital Hanoi, and require up to US$ 58 billion in investment. Its sea port would accommodate 25 vessels ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 tons and handle 280 million tons of goods per year. The industrial zone would include heavy, medium and light industry, upstream and downstream petrochemical complexes and a steel mill. Coal-fired power plants with a total capacity of 4,000 MW and a 214 MW hydroelectric dam and water storage reservoir would be built, along with accompanying residential, recreation and commercial zones. Most importantly, the project would also include a 160 km highway and rail link east into Thailand with oil and gas pipelines and electrical transmission lines along the same right-of-way.

However, the project has been plagued by investment and political challenges. Citing, “The will of the people,” in January 2012 the Myanmar government abruptly cancelled the 4,000 megawatts coal fired power station to be built by Ratchaburi Electricity Generating Holdings, a sister company of Thailand’s state owned Electrical Generating Authority.

In mid 2012 ITD’s key Myanmar local partner, Max Myanmar, pulled out entirely. ITD’s inability to recruit sufficient new financial partners then brought preliminary construction to a halt.

Infographic by: The Mekong Eye. Click to enlarge.

Taking the First Step

The government of Thailand stepped in and negotiated a new agreement with Myanmar in late 2013. A 75- year concession rights for DSEZ development were transferred to a new company, structured as a “Special Purpose Vehicle” (SPV) jointly owned (50:50) by the governments of Myanmar and Thailand. However, little progress was made by the time the Thai military staged a coup in May 2014.

In December 2014 the Thai military government announced its commitment to revive the project by inking a new agreement with the Myanmar government. To Myanmar, such revival is like “renovating some parts of the old house in order to prevent the old house from collapsing.” This in turn spawned commitments from Japan to consider assisting the Thai and Myanmar governments to develop the DSEZ. Japan also agreed to entertain support for an 874-km railway linking Dawei to Thailand’s Eastern Seaboard and further east to Cambodia. In July 2015, Japan, Thailand and Myanmar inked an agreement that set the stage for a scaled-down, initial phase of the project encompassing just 32 square kilometers – or about three quarters in size of Thailand’s largest industrial estate, Map Ta Phut, along its Eastern Seaboard.

China has expressed interest in the project. In March, ITD announced it has formed a consortium with Chinese companies to pour investment into new infrastructure projects in DSEZ, as land lease in the initial phase kicks off. The consortium will consist of private and state-owned Chinese companies which will focus on the 132-kilometre, four-lane road and three ports. These facilities will require an investment of US$800 million.

Unsettled resettlement

While the Dawei project was stalled, increasing documentation emerged regarding social and environmental impacts incurred as a result of site preparation and preliminary road construction.

In 2014 it was estimated 20-36 villages, (comprising approximately 4,384 – 7,807 households or 22,000 – 43,000 people), would be directly affected by the construction of the DSEZ and related infrastructure. This included 1,000 people from Ka Lone Htar village who have been resisting displacement by the 627 million cubic meter reservoir project for DSEZ water supply.

A rice farmer works in a field inside the planned Dawei SEZ in Nabule, Burma. (Photo by Taylor Weidman/Getty Images)

Contrary to the Thai government’s claim that resettlement has been done with World Bank’s standards, ground surveys between 2013 and 2014 stated “critical flaws” in land confiscation, resettlement and compensation process. Affected communities were given limited information about DSEZ and their ultimate displacement. Of 20 villages surveyed only 15 percent of all households reported having received compensation. And for them the amounts received have mostly been inadequate to sustain their family’s future. Resettlement arrangements have also been reportedly inadequate and the living standards of those resettled have been considered lowered, leaving many to local concerns.

Now that Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD-led government is taking power on March 30, local people and civil society organizations have urged the new government to reconsider the DSEZ project by reviewing the agreement signed by the outgoing government. They said the Burmese, Thai and Japanese governments needed to solve existing problems related to the project before pushing ahead with its implementation.

Thailand’s leading environmental economics think tank, the Healthy Public Policy Foundation, is concerned about the reported social impacts could be much broader. The group’s 2012 report urged both Thai and Myanmar governments to undertake a comprehensive cumulative environment, social and health impacts assessment of the project. They cited the tremendous unintended impacts that resulted from Thailand’s Eastern Seaboard project, which when launched nearly four decades ago, was dubbed the “dawn of Thailand’s development era”. Its Map Ta Phut Industrial Estate has become world renowned for its airborne chemical pollution, soil contamination and extensive health impacts to surrounding communities. Increased civil society pressure at Map Ta Phut and elsewhere in Thailand has been cited as a motivator for shifting industrial development to Dawei.

Construction workers build a small, interim port inside the planned Dawei SEZ near Ngapitat, Burma. (Photo by Taylor Weidman/Getty Images)

Additionally, plans for the road and rail link between Dawei, Bangkok and the Eastern Seaboard project will affect many communities within the transport corridor. Furthermore, concerns are now being raised regarding the cumulative impacts of the expansion of this corridor further east, across Cambodia to Vietnam’s picturesque seaside city of Quy Nhon.

In 1998 the Asian Development Bank first identified the potential for a GMS economic corridor from Dawei to Quy Nhon. But the bank’s involvement in such an initiative could not move forward since the ADB was prohibited from engaging bilaterally with Myanmar during its three decades of military rule. Earlier this year, however, the ADB has expressed interest to become involved in Dawei should Japan follow through with its intention to invest in the DSEZ.

Realization of this 2,200 km-long GMS Southern Economic Corridor received a sizable boost in 2014 when Vietnam announced that its coastal city of Quy Nhon would house the largest refinery and petrochemical complex in the region. It would be developed and operated by PTT Plc, Thailand’s top energy company, and Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest oil producer. Known in Vietnam as the Victory Project, the US$22 billion refinery is designed to refine 20 million tons of crude oil annually – 400,000 barrels per day. PTT plans to begin construction in 2016 and start operations in 2021. This project has drawn interests from Thai and Singaporean investors to set up industrial estates nearby. Expansion of Quy Nhon’s airport, deep sea port and highway linking central Vietnam to neighboring Laos and Cambodia are also underway.

The Binh Dinh provincial authority, charged of overseeing the project said that they expects future traffic of raw materials and finished products between Quy Nhon and Dawei along the corridor identified by ADB once transport links are completed. There are also reports that Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen has expressed interest in attracting investors to develop industries along the Cambodian section of the corridor.

However, the current fall in the oil price may have caused investors to delay starting the oil refinery projects.

Corridor’s SEA urged

The overall impact of building out Dawei, Quy Nhon with their connecting transport links should be considered in a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA), advises Dr Dejrat Sukamnoed, head of Healthy Public Policy Foundation. In 2012 he undertook an initial desk impact assessment for DSEZ and recommended an SEA, citing Thailand’s experience with Map Ta Put.

He said that if Japan and the ADB are to get involved in the DSEZ, particularly given the potential link to Quy Nhon and resulting economic corridor, both entities should ensure an SEA is conducted and cumulative impacts are assessed as such analysis is consistent with the policies of both lenders.

The above photographs were produced by Taylor Weidman/Getty Images in collaboration with The Mekong Eye and Mekong Matters Journalism Network, with full editorial control to the journalist and their outlet. All images are owned by and available for purchase from Getty Images

The infographic is a Mekong Eye original and may be reproduced and republished under Creative Commons licencing.