Dam Chan handed over the food in exchange for riel as she described hearing the loud bangs of dynamite in the distance.

The 55-year-old has farmed and sold food in Preah Rumkel commune her entire life and is concerned about the future of her home now that construction on the nearby Don Sahong Hydropower Dam has started to affect the local wildlife, and subsequently the lives of those residing near the Lao border.

Residents of Preah Rumkel commune in Thala Barivat district, Stung Treng province, have been demanding authorities suspend construction of the dam to no avail. The project has taken on a new life for local residents now that the booms of dynamite blasts and the sounds of rocks smashing under the weight of machines have become an ever-present part of their daily lives.

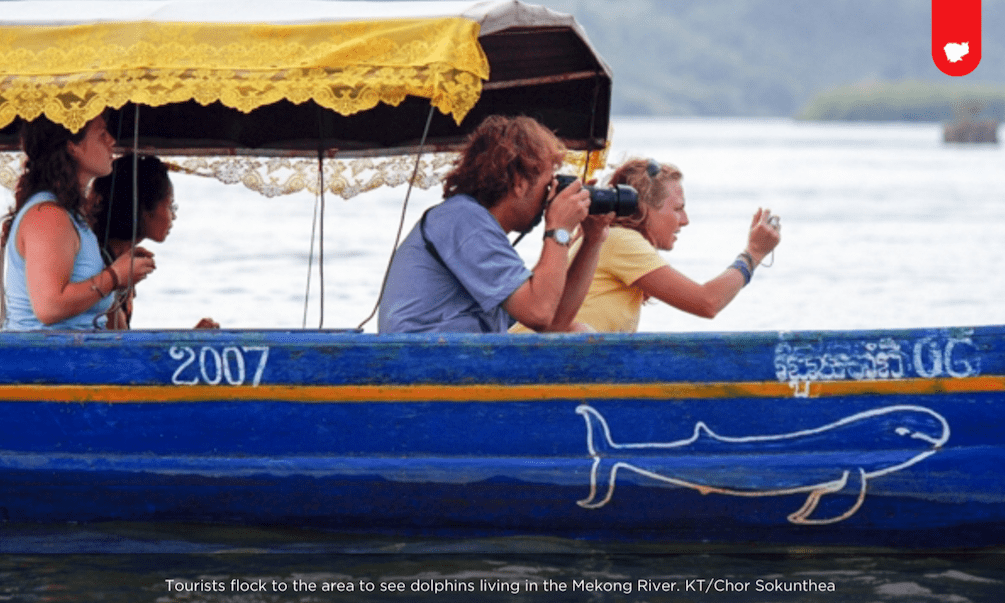

But what residents of Preah Rumkel commune are most worried about is the loss of the dolphins that are native to Anlong Chher Teal, which attract tourists and provides incomes for people in the area.

“I am concerned not only about the dolphins, but about the people because of the hydropower dam,” she said. “If all the fish are dead, what can we eat? If the dolphins are gone, no tourists will visit.”

Every evening she can hear explosions from the Lao side of the border as construction teams lay the foundations for the dam. Despite claims from the Lao government and the dam’s builders that it would have no effect on the local wildlife, residents of Preah Rumkel have noticed an immediate change in the migration patterns of dolphins living in the area.

“I only saw three dolphins today,” Ms. Chan said. “It is because Laos is using explosives to build the dam’s foundations.”

The explosions have severely disrupted the local ecosystem, killing scores of fish and pushing dolphins further downstream. Since her childhood, she has seen 20 to 30 dolphins swimming and playing in the water each day. But these days, it’s down to two or three.

She blew out the fire on her stove as she turned and said: “In the future, when there are no dolphins anymore, tourists won’t visit.

“If there are no dolphins, what thing will they come to look for?” she asked. It was unfortunate, she said, that only three or four years after building a road and seeing an increase in the number of tourists, the number of dolphins seen in the area was decreasing due to the dam’s construction.

The Don Sahong Hydropower Dam is located in Siphan Don, southern Laos, about 1,500 meters from the Cambodian border in Stung Treng province. The 30-meter high, 7km long dam will produce between 240 and 360 megawatts.

The construction company working on the dam, Mega First Corporation Berhad, claimed to have already done an environmental impact survey before starting their work. They say the study showed no evidence of potential damage to the local ecosystem.

Thang Ban, a 17-year-old vendor in Preah Rumkel, said she no longer saw packs of dolphins as she once did. People in her community tried to protest against the dam’s construction, but were met with fierce resistance and outright denials by the Lao government.

“To stop the project, I went to protest several times,” she said. “But I did not see any results.”

Other residents echoed Ms. Ban’s sentiment, but none more forcefully than Bun Thorn, a 44-year-old running a dolphin sightseeing boat tour in Preah Rumkel. Like Ms. Chan, he has lived in the area his entire life and said the dam was disrupting his business, and more importantly, his home.

Of the many effects from the dam he mentioned, water irregularity was chief among them. The massive increases and decreases in water levels have caused a litany of problems for local residents trying to adjust to river patterns different from those they have spent their entire lives adhering to.

Mr. Thorn also said the use of TNT by the construction teams working on the dam has disrupted fishing in the river, forcing fishermen to collect large bales full of dead fish all at once instead of gradually fishing on the river as they used to. The frequent explosions have led to fish avoiding the area altogether, and many residents are now fishing farther downstream because of it.

“When they use the grenades and TNT, the explosions impact their [the fish’s] health, so that is why they are moving,” he said.

As he prepared his boat for the next tourist trip out on the river, he said he noticed visible changes in not only the number of dolphins in the area, but the quality of the water.

“From 2006 to 2016, the water here is so different. It has become dirty and algae and fish have begun to decrease,” he said. “Without conservation, it will be lost easily. And people living here will also be affected by no dolphins. I urge the government to look at people who are living far away.”

‘Study the Impact’

“From 6am to 7 pm, the Lao side starts using explosives and they use it twice a day,” said Preah Rumkel commune chief Yin Vuthy. “It makes a blast wave and sound to animals and people. Before the blasts, they have three alarms before they start digging and removing rocks.”

Mr. Vuthy has joined other residents in asking for intervention from the government to stop Laos from building the Don Sahong dam due to its dire effects on their community. But they have yet to receive any response from the government.

“We did not say they should not build it,” he said. “We just want them to study the impacts first. We strive to protect the area near the border and it is hard work, but Laos is not preserving their end.”

He echoed similar statements of others in the area, saying the blasts were forcing fish and dolphins away from the border and robbing the community of one of its main financial lifelines.

“If there are no dolphins in this area, it will have no potential,” the commune chief said. “It will not only affect tourism, but affect the livelihoods of the people who are living here.”

Even Lao nationals on the other side of the border have complained about the dam to their government, citing similar claims as the Preah Rumkel commune residents.

“They told me that they could not do anything against it because it was a government project,” Mr. Vuthy said as he stared out across the border.

“They built this dam near us, but if there is risk, who is responsible?” he asked. “Everything is the same here. The fish were the first ones affected, so they fled first. Next it will be the dolphins, and then it will be our turn because of the lack of income.

“When the area floods, how can we live?” he exclaimed before turning his eyes away from the border.

Dolphin Sightings Decrease

Despite the creation of a two-kilometer preservation area along the Sopheak Mith section of the Mekong River, the number of dolphin sightings has decreased. Mr. Vuthy said that by last November, only three dolphins were frequenting the area. Now, there are only two left.

“In 2015, one dolphin died,” he said. “The death of a dolphin is a sign that the tourism sector is at high risk of potential loss.”

Sous Chanphal, the second deputy chief of Preah Rumkel commune, highlighted the use of explosives as particularly damaging to the area and its resources and questioned why the company building the dam was using it so indiscriminately.

“The use of explosives not only kills a lot of fish,” he said. “This causes great concern to our residents’ health. Our citizens’ health is affected due to the use of water from the river.”

Many environmental groups have disputed

Mega First Corporation Berhad’s claim of no environmental impact for the simple fact that the company’s Environmental Impact Assessment has yet to be released to the public.

Despite the visible and visceral effects seen after the initial construction phases, the company has insisted that the dam will have no effect on the environment once it is finished. But environmental activists have said the six million Cambodians living along the Mekong River can already see its impact on the environment and the local wildlife.

According to a WWF report, there were more than 200 dolphins in Cambodia in 1997. That number fell to 85 by 2010 and now, only 80 remain.

In their report, they specifically mention the effect construction blast waves have on dolphins, which use sound waves in the water to send messages to each other. These constant blasts disrupt dolphins’ ability to understand messages and can confuse them. Between the TNT blasts, the increased boat traffic along the river and other damage done to their habitat, the dolphins are being forced downstream or away from the Mekong entirely.

Laos Deputy Prime Minister Somsavat Lengsavad has told Foreign Minister Hor Namhong that the dam will have no effect on countries in the lower Mekong area, directly refuting reports from other environmental organizations citing specific data that showed incredible changes in the ecosystem around the dam’s construction site.

In March, Prime Minister Hun Sen brought the issue to the attention of Laos’ prime minister during a state visit to Vientiane, asking his Lao counterpart to “do everything they could to ensure the sustainable use of water.”

General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party, Bounnhang Vorachith, told the premier: “Laos will strive to ensure that it will not affect neighboring countries. Laos has studied the effects carefully.”

There has been no update from the government on whether they have actually checked with the Lao government on this issue since then.

Laos started construction on the Don Sahong dam in October 2015, even though the four countries in the Mekong River Commission – Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and Vietnam – agreed in June 2015 to discuss the issue before the dam was started.

Director of the NGO Forum Tek Vannara said his working groups have already discovered damning evidence of widespread impacts rooted in the Don Sahong dam. Between the biodiversity impact, the loss of dolphins, the change in water flow and the loss of fish traffic, Mr. Vannara said it was clear the dam was having an indelible impact on the area surrounding it.

He said the Hu Sahong river waterway, which now has a dam in Champasak province in Laos blocking 30 percent of its water, was the only river where fish migrated downstream and laid eggs upstream. The blockage of this waterway has already affected the fish in the area.

“Until now, they have not seen the Lao side express any willingness to discuss this with other parties or people who live along the Mekong,” he said. When the Don Sahong is finished, it will block off most of the Hu Sahong Canal, a large creek along the Mekong in Laos and Cambodia.

The unwillingness to even discuss the dam with local residents being acutely affected by it has roiled Cambodians living in the area, especially Ms. Chan, who has seen her business dwindle since the onset of the dam’s effects.

Ms. Chan thought back to when construction on the dam started while closing her shop for the night.

Before handing her last customer his change, she whispered under her breath: “The dolphins move today, and I will probably have to move tomorrow.”

When asked why, she only shook her head.

“Flooding and no business,” she said.

A woman sells food to tourists near the Mekong River in Stung Treng province. KT/Chor Sokunthea

A dolphin makes a splash in the Mekong River in Stung Treng province. KT/Chor Sokunthea

This story was produced in collaboration with The Mekong Eye and Mekong Matters Journalism Network through a field visit for journalists organised in partnership with Cambodian Institute for Media Studies. The journalist and their outlet retain full editorial and copyright control.

One reply on “Don Sahong vs Dolphins: How the Dam Is Affecting Local Residents”

Comments are closed.