SURVIVAL OF THE Mekong giant catfish is at a critical point, with the species on the brink of extinction in the wild due to development projects along the Mekong River, experts have warned.Meanwhile, local people said they feared their traditional culture associated with catching Mekong giant catfish would slowly disappear.

The Mekong giant catfish (Pangasianodon gigas) is ranked as critically endngered on the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The largest freshwater fish in the world, its natural habitat is the Mekong River from China to Cambodia and Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia.

Mekong River Commission (MRC) senior aquatic ecology expert Chavalit Vidthayanon said the wild population of the giant catfish in the Mekong had been reduced by 90 per cent and its survival was under serious threat from development, including dam projects, according to the latest estimates.

“The number of Mekong giant catfish has been decreasing significantly. Researchers believe that the surviving small population is now living in the deep pools in the river between Laos and Thailand from Loei to Ubon Ratchathani, but it is impossible to determine the exact number of fish,” Chavalit said.

“This fish has a spawning ground at the river in Chiang Khong district in Chiang Rai, so the dam development projects such as Xayaburi Dam and Pak Beng Dam will block the migration passage of the fish, putting even more pressure on a near-extinct species.”

Chavalit urged countries in the Mekong River Basin to work together to save the Mekong giant catfish from extinction in the wild and explore possibilities of allowing the fish to migrate through the dams.

“I understand that it is hard to ask for the dam projects to be cancelled, but Mekong giant catfish cannot climb up a fish ladder, so we have to find alternative ways to let the fish get to their spawning area,” he said.

He also expressed concern that although the fish could migrate up to Chiang Khong, a plan to create a shipping route to Luang Prabang in Laos from China is likely to disrupt fish reproduction.

“The fish need a stable level of river flow, good quality of water and environment for breeding. The frequent movement of large cargo barges in that part of the river may affect reproduction,” he said.

Rian Jinarath, a local expert in Mekong giant catfish traditions in Ban Haad Krai, Chiang Khong district, said that even though catching the catfish has been banned since 2006, the species has already disappeared from that part of the river.

“We do not catch Mekong giant catfish anymore. It is illegal now and there are no fish for us to catch anyway,” Rian said.

Mekong Giant Catfish in local market (Photo: The Nation)

He said people of Ban Haad Krai caught Mekong giant catfish for generations before the ban and it was an annual village tradition to perform a religious ceremony honouring the holy spirit of the river to allow them to catch Mekong giant catfish.

“The season for catching Mekong giant catfish lasted only for three months, from April to June. According to our folklore, we believe that they live in the underwater caves in the Mekong at Luang Prabang, guarded by the holy spirit of the river, and they will be allowed to travel north only after the Songkran festival,” he said.

“When I was young, this fish was abundant, but after our society was modernised, there was more pollution and ecosystem degradation such as the construction of dams upstream and the building of concrete embankments, which made the fish population decrease.”

Rian also warned that the demolition of rapids and islets in part of the Mekong to create a navigation route would make the situation worse, as the rapids provide habitat and food sources for fish.

Samian Thanareuang, a fish seller in Chiang Khong market, said that although the Mekong giant catfish was still available for customers, all were farmed fish.

“There have been no wild fish from the Mekong River for a long time. This is not only the case for Mekong giant catfish, but other types of fish too. The fishermen cannot catch fish in the river anymore,” Samian said.

The Fisheries Department has been artificially reproducing the Mekong giant catfish in captivity since 1983, releasing the fish into large reservoirs across the country, but the species continues to dwindle in the wild. Meanwhile, in Luang Prabang, wild Mekong giant catfish still can be found at the city’s famous morning market.

Aorn, a Lao fish seller, said that freshly caught Mekong giant catfish from the river were still available there, even though the fish was very rare out of the season from May to June.

“I buy Mekong giant catfish from the fishermen and sell to the market, but I do not have this fish every day. Mostly they are caught in Xayaburi and Luang Prabang provinces,” Aorn said.

“In the past, Mekong giant catfish could be found easily, but I have no idea why this fish has become rarer. Many consumers like this fish, so I hope it will become abundant again.”

This story is part of an investigative series on the development works undertaken in Mekong River Basin, the next story will be the impact of the new dam project in mainstream of Mekong River in Laos, Pak Beng Dam, to the local communities. See also: Mekong Diplomacy and River Blasting.

This series was produced in collaboration with The Mekong Eye and Mekong Matters Journalism Network. The journalist and their outlet retain full editorial and copyright control.

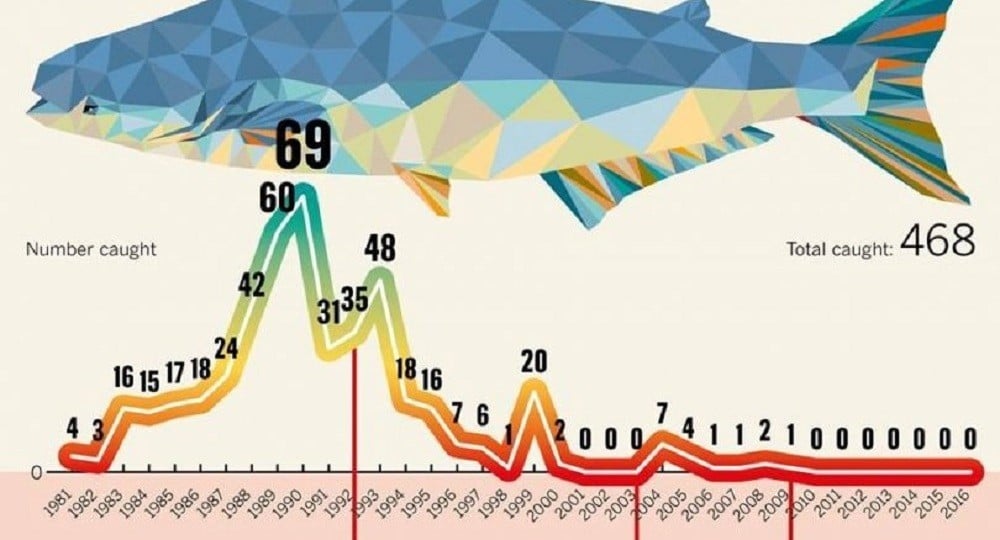

Photo: Decreasing number of Mekong giant catfish (Photo: The Nation)