Over the past decade, Chinese investors have moved in, building shopping malls and casinos and glitzy hotel complexes and importing a way of life that is a long way from the traditional norms in Laos – an impoverished landlocked nation where 80 percent of the population still scrape a living from small-scale farming.

And the enclave is far from being an isolated case. One by one, communities across northern Laos are gradually taking on the appearance of de facto Chinese dependencies.

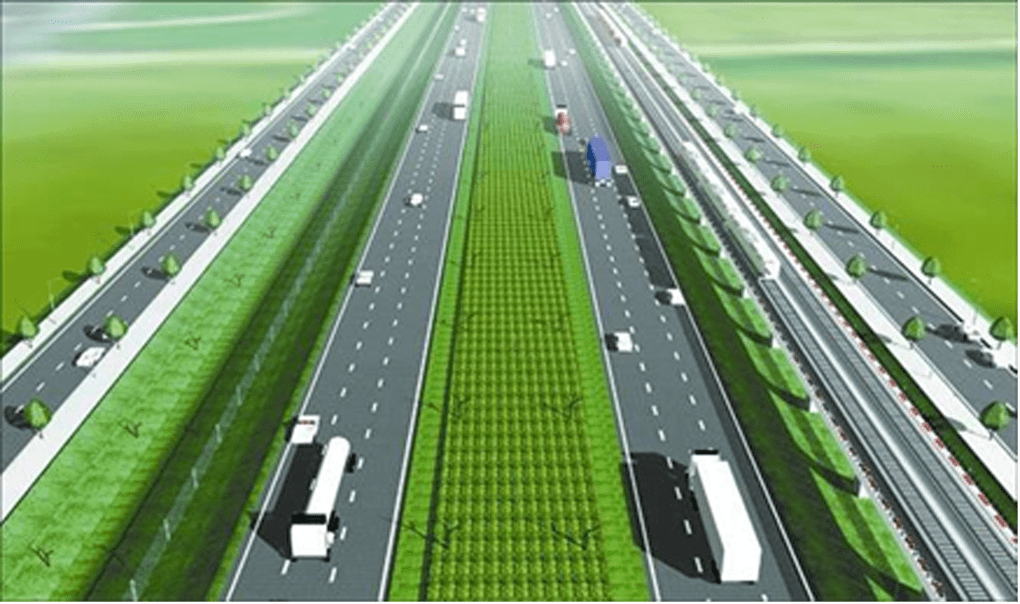

Tourism, transport, property, energy, high-intensity agriculture … with the blessing of the Laos government, China has set out to develop, some say exploit, the potential of its hard-pressed neighbour.

Given the country’s desperate need for foreign investment, the Laotian authorities clearly believe that the economic advantages of the relationship outweigh any drawbacks of surrendering sovereignty.

But critics say the consequences for the indigenous population of this unbridled, spill-over capitalism are truly dire – ranging from gambling, prostitution and illicit trade in the newly urbanised border communities to widespread land expropriation, deforestation and pollution in the rural hinterland.

Furthermore, the profits and benefits of all this activity flow back to the Chinese rather than to the locals.