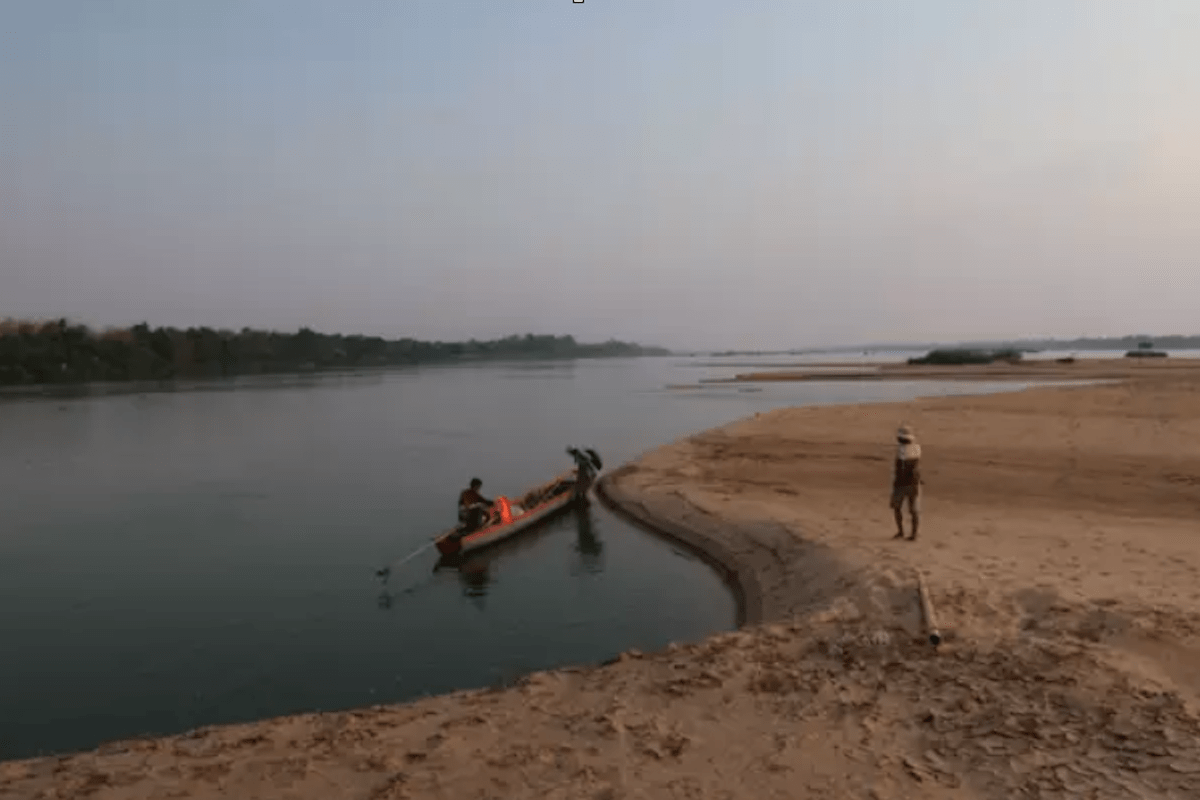

On a bucolic stretch of the Mekong, near Cambodia’s northern border, people can tell you all about hydropower. The dam is why fish catches have been dropping, steadily, for the past few years. The dam is why so many young men have taken up logging jobs of dubious legality. The dam may mean development, some local people concede, but they say it won’t be for them.

Despite many campaigners’ and activists’ best efforts, major hydropower projects have remained a cornerstone of development plans in the Mekong region for years. But as new bodies of data emerge on the real potential economic and environmental costs of large dams, countries in the region are beginning to show some tentative signs of rethinking their options — even amid a major boom in dam projects.

“People in rural areas like this, our main food is fish. When they build the hydropower dam, it means that they kill us,” said Thit Poeung, a 40-year-old father of five from Koh Preah village, a teardrop-shaped island of fishermen and farmers, surrounded on all sides by the Mekong.

“Development means for the rich. The poor are still poor because they don’t benefit from that development. Who is that development for then?” Thit Poeung questioned.

“In a hydropower project, often it’s specific individuals in government and business that experience most of the gains, while it’s the local population that loses through diminished fisheries, changes in water supply or quality, or resettlement.”

— Ida Kubiszewski, associate professor at ANU Crawford School of Public Policy

People in this part of Cambodia tend to know about hydropower, because they are surrounded by it. Go 50 kilometers in any direction and you will hit a proposed dam, a dam under construction, or a completed hydropower project. Due north on the Mekong, just over the Laos border lies the Don Sahong dam, a 260-megawatt project, which broke ground in January 2016 — despite significant outcry from neighboring governments. Halfway between lies the proposed Stung Treng dam, about which little is known. Travel downriver and you’ll hit the planned Sambor dam, which is still being studied, but has been proposed to be as large as 3300-megawatts. Northeast, on a major Mekong tributary called the Sesan River, lies Cambodia’s newest dam, the 400-megawatt Lower Sesan 2, which went online last September.

The dams here are just a fraction of what is planned for the lower Mekong basin, which encompasses Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Eleven dams are planned or in construction on the river’s mainstem, with dozens more set to be built on tributaries like the Sesan.

Mekong area governments have long insisted that this proliferation of dams is needed to propel forward their rapidly growing economies and ensure their continued development. Among the lower Mekong nations, Cambodia and Laos both average around 7 percent GDP growth annually, Vietnam had 6.2 percent growth last year, and Thailand — which saw its GDP plummet after the 2014 military coup — reached 3.2 percent growth last year. By comparison, the GDPs of the U.S. and U.K. grew by less than 2 percent last year.

Energy demand for the Lower Mekong Basin is projected to grow 6 to 7 percent annually, and hydropower has long been a cornerstone of these four nations’ development plans. The planned mainstem hydropower projects total almost 13,000MW and cost nearly $30 billion. Another 30 dams planned on major Mekong tributaries have a capacity of more than 10,000MW at a cost of $20.6 billion. If all 11 dams are built, they are projected to meet between 6 and 8 percent of the Lower Mekong Basin’s energy needs.

Those figures were all developed by the Mekong River Commission, an intergovernmental organization aimed at equitable management of the shared river. In its own initial studies, released in 2011, the MRC estimated that the 11 dams would generate a net economic gain of $33.4 billion, basinwide. Last year, they released revised calculations suggesting economic gains could be higher than $160 billion over the next 24 years.

Such sums have often been the cornerstone of government arguments, which point out that hydropower is a sustainable way to meet its energy needs. Even if individuals find it harder to catch fish on a daily basis, or if changes in sedimentation adversely affect individual farmers, the economy as a whole rises — or so the argument goes.

New data tells a different story

But some of those assumptions are now being questioned. Last week, at the MRC Summit — held every four years — the group presented dramatically more complex findings from a six-year council study. The reports, which run in the thousands of pages and have been disseminated at various intergovernmental meetings since late last year, present a far more complex look at the trade-offs of hydropower. Food insecurity will rise, flood damage will worsen, and the “effects of poverty will remain.”

Hydropower would generate earnings — the macroeconomic assessment found that by 2040, the lower Mekong basin could see economic gains of more than $160 billion. But those earnings come with costs far higher than previously believed, the study found. The decline of fisheries could cost nearly $23 billion by 2040. The loss of forests, wetlands, and mangroves may cost up to $145 billion. With more than 90 percent of sedimentation blocked, rice growth along the Mekong will be severely curtailed. Fish farms, irrigation schemes, and expanding agriculture could offset these losses — but with uneven results between classes and countries.

Crucially, the reports also raise the question of what, precisely, development means, noting in the key messages that “poor households along the Mekong River are likely to be most disadvantaged, but the urban poor are also likely to face considerable challenges as fish prices are expected to increase.”

“From an economic perspective, some individuals may still push for hydropower … but in a few years from now, investors won’t be interested.”

— Alex Smajgl, managing director of Mekong Region Futures Research Institute

Armed with new knowledge on the adverse impacts, countries in the region are increasingly weighing the role of hydropower. In February, Thailand’s electricity authority delayed signing an agreement to purchase power from the planned Pak Beng dam in Laos. Pak Beng was slated to sell 90 percent of its electricity to Thailand and was planned to be the third large Mekong mainstream dam in Laos. Thai fishers and environmental activists had long campaigned against the dam, saying it would have outsized impacts on downstream communities.

In February, Apisom Intralawan, together with colleagues David Wood and Richard Frankel at Mae Fah Luang University in Thailand, published findings from a remodeled economic survey. They concluded that the economic impact of planned hydropower projects in the lower Mekong basin is a net negative: $7.3 billion, to be exact.

Released in Ecosystems Services journal, the paper, which was co-authored by several other researchers at Mae Fah Luang and the Australian National University, forecasts in particular “huge negative economic impacts for Cambodia and Vietnam.”

Like the council study, their research recalculated the hydropower benefits and the loss of capture fisheries — which it found had been grossly underestimated in the early MRC reports. The new calculations also take into account impacts that were ignored in earlier studies — the costs of social and environmental impact, as well as sediment reduction (dams block nutrients from reaching farmland.)

“The bottom line is that even with the most conservative assumptions about external costs, the NPV [Net Present Value] of these projects is still negative, meaning the project is not economically viable,” the report concludes.

Alex Smajgl, managing director of the Bangkok-based Mekong Region Futures Research Institute, carried out several of the impact assessments for the MRC Council Report.

“Hydropower is on the verge of becoming irrelevant for the Mekong,” he predicted. Like Wood, Smajgl believes the plummeting price of solar and other alternative energy sources will lead to a seachange in how the lower Mekong basin seeks to close its energy short fall.

“Last year was a turning point for the whole sector,” he said. “From an economic perspective, some individuals may still push for hydropower … but in a few years from now, investors won’t be interested.”

Too often, development and economic growth are conflated, said Ida Kubiszewski, an associate professor at ANU Crawford School of Public Policy, and one of the co-authors of the ecosystems services study.

“It’s not just about total costs and benefits; it’s also about who gains and who loses. In a hydropower project, often it’s specific individuals in government and business that experience most of the gains, while it’s the local population that loses through diminished fisheries, changes in water supply or quality, or resettlement,” Kubiszewski explained.

Effects on the ground

Those living on the river say they hardly need such studies to confirm what they see in front of their eyes daily: this type of development carries a steep cost.

Cheam So Phat, a studious 37-year-old, is just one of scores of men in Koh Preah who have had to migrate to survive. Both Phat and his younger brother have spent years in Thailand working as illegal factory and plantation laborers. The work pays enough to survive, not save, and yet that’s more than they can expect in their home village.

It’s hard to survive here, said Phat. “We’ve lost the forest, we’ve lost river resources. They were the main source for us to earn a living and to eat. Now you have lost this stuff — how could you survive in the future?”

While Phat spoke, he mended a fishing net. The Mekong — just meters from his house — used to teem with fish. In recent years, the catch has dropped precipitously. If there is a development angle to hydropower, said Phat, it is not one that touches his life.

“I’ve heard about the project to build the hydropower dam, but I don’t know how the word development is connected,” he said. “If they build more dams, I hear it’s really going to affect fish here,” said Phat. He said he has seen these impacts firsthand.

“You do this observation. You know when there is meant to be more fish and when there is meant to less fish. If it’s past the time and there’s still less fish, that means they closed the dam, they turned the water system off — the water level isn’t changing and the fish aren’t coming. Before in dry season you get less fish because its low water, rainy season you get more fish. But now, in every season you get less fish.”

For years, impacts like these simply weren’t viewed to outweigh the benefits of hydropower. But some are beginning to believe that shifting economic realities may finally push governments and investors to conclude the costs are too high. After two decades of promoting hydropower as a sustainable means of development, the MRC’s latest findings don’t mince words.

“Considering the irreversible effects and path dependency of hydropower development in the LMB, it is strongly recommended that current and future energy planning includes consideration of other renewable power generation technologies as these are increasingly being viewed as less environmentally-damaging alternatives to hydropower,” the study said.