Organized crime groups in Asia’s Mekong region have intensified the production and trafficking of highly-addictive methamphetamine, extending the illegal trade into countries such as Australia, Japan and New Zealand, senior drug policy leaders warned on Monday at a United Nations-backed regional conference.

(See also: Mekong rethinks drug policy as syndicates pump meth from Myanmar, and Thai troops seize record meth haul on Myanmar border.

“Significant changes have been underway in the regional drug market for a number of years now,” Jeremy Douglas, Regional Representative of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), told the conference, which opened in Myanmar’s capital, Nay Pyi Taw.

“Responding to the situation requires acknowledging some difficult realities, and agreeing to new approaches at a strategic regional level,” he added.

The conference brings together senior drug policy leaders from Cambodia, China, Lao, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam to consider the latest data, and discuss drug law enforcement, justice, health and alternative development strategies and programmes.

It also reviews the implementation of the last Mekong strategy that the countries agreed under the so-called Mekong Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Drug Control and negotiates a new strategic plan.

The Mekong has long been associated with the production and trafficking of illicit drugs, particularly heroin, but has undergone “significant transformation” in recent years, according to UNODC.

Opium and heroin production have recently declined, while criminal gangs have intensified production and trafficking of both low grade yaba methamphetamine – commonly known as meth – and high purity crystal methamphetamine, to “alarming levels”.

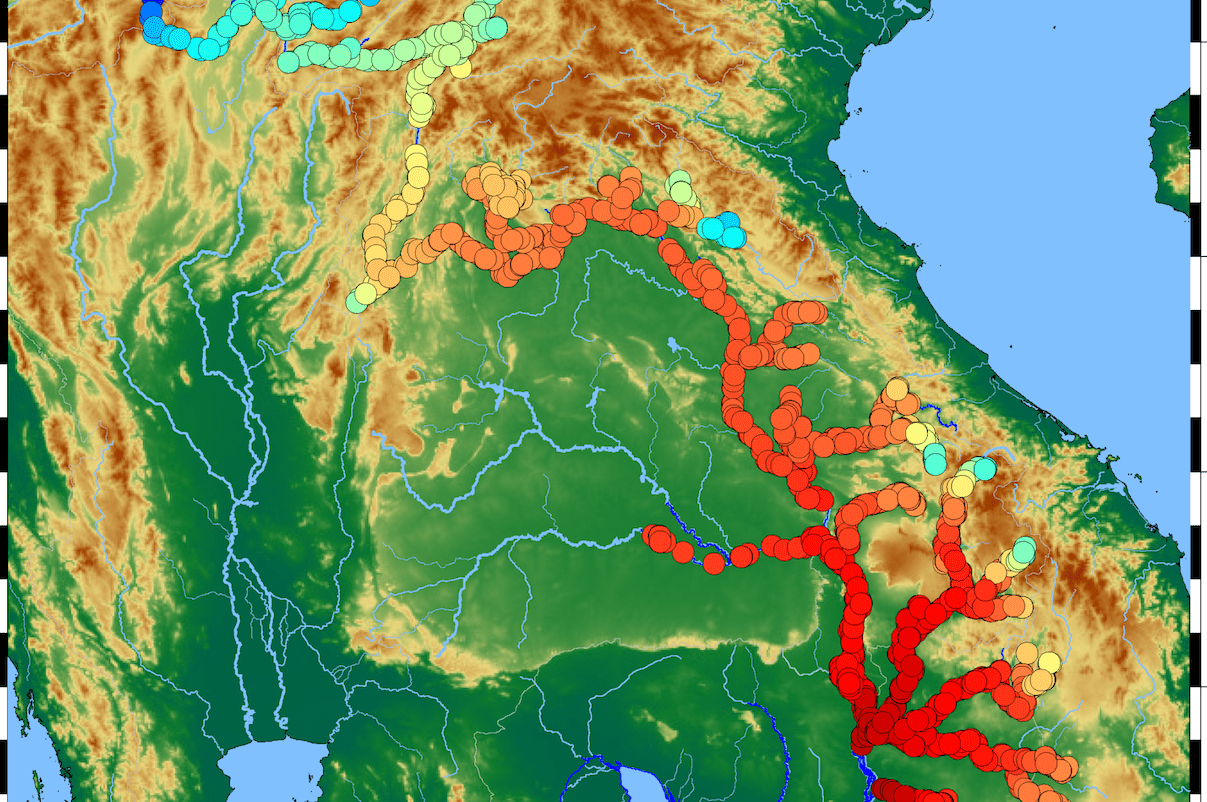

Several Mekong countries have already passed the total number of seizures for all of last year, just a few months into 2018, and methamphetamine from the Golden Triangle – the border areas of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar – is being seized in high volumes across Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Malaysia, Indonesia, UNODC said.

For affected countries, the shift to synthetics like methamphetamine is particularly difficult to address; partly because the remote and clandestine makeshift laboratories where it’s manufactured, can easily be moved.

“Methamphetamine and heroin are currently estimated to be worth US $40 billion in the regional drug market,” said UNODC Advisor Tao Zhiqiang. “Effective coordination between countries is essential and the Mekong MOU remains the best vehicle available for this coordination.”

He stressed that law enforcement operations are part of the solution, but addressing growing regional demand is also important.

The Mekong MOU has provided a platform in recent years for the countries to agree to standard operating procedures for multi-country law enforcement operations, as well as a framework to exchange ideas and experience.

In a significant development, the Mekong MOU was aligned last year with the recommendations that came out of the UN General Assembly Special Session on tackling illegal drugs on a global level, ensuring a strong emphasis on reducing demand and the impact on health.

The recommendations also include creating alternative development programmes, to provide alternative means of income for communities where drugs are being made, and beefing up law enforcement targeting the criminal gangs at the centre of the trade.