The government of Myanmar should promptly provide redress for past illegal confiscations of land, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The government should also enact laws and regulations to safeguard the rights of farmers and other small landholders from future confiscations.

Over the past 30 years, Myanmar government and military officials have seized vast swathes of land from farmers while providing them no or inadequate compensation, which denies them livelihoods and erodes access to basic services. Many farmers have faced criminal prosecution for protesting the lack of redress and refusing to leave or cease work on the land that was taken from them.

“Widespread land confiscations across Myanmar have harmed rural communities in profound ways for decades,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director. “Aung San Suu Kyi’s government should promptly address illegal land confiscations, compensate aggrieved parties, and reform laws to protect people against future abuses.”

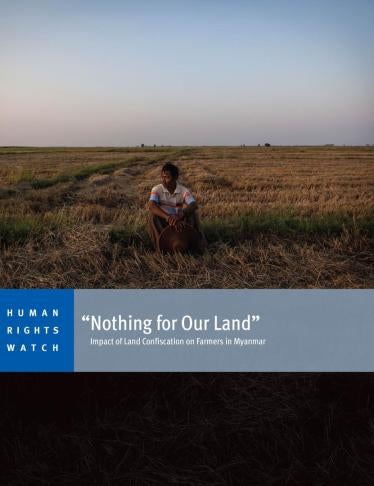

The 33-page report, “‘ Nothing for Our Land’: Impacts of Land Confiscation on Farmers in Myanmar,” documents the devastating effects of land confiscations for farmers in southern Shan State and the Ayeyarwady and Yangon regions of Myanmar. Farmers describe their loss of livelihoods, access to health care, and children’s education, and their efforts to obtain redress, which frequently ends in arrest.

In researching the report, Human Rights Watch spoke with 39 farmers in Myanmar, as well as experts on land, and civil society groups.

Widespread land confiscations across Myanmar have harmed rural communities in profound ways for decades.

Phil Robertson

Deputy Asia Director

Land confiscations have long plagued the rural population of Myanmar under repressive military juntas. While official statistics confirm that the government took hundreds of thousands of acres since the early 1990s, activists believe millions of acres were seized. Military government confiscations often occurred with little or no notice and inadequate compensation, and have a profoundly harmful impact on those affected.

Thein Win, 61, from the Ayeyarwady region, told Human Rights Watch he had no prior warning when the government took 12 acres of land from his family: “I didn’t know, they just took it.” He said he was threatened with jail for complaining about the seizure, provided no compensation, and was then forced to dig fish ponds for the government on his seized land. “We got nothing,” he said. “We literally got nothing for our land.”

Many farmers described the impact of the sudden confiscations on their livelihoods. “We were starved because we didn’t have any business or job to get any income,” said Thein Win, 61, in the Ayeyarwady region. He said that after his land was taken his family could barely afford to eat two regular meals a day.

“Nothing for Our Land”

Impact of Land Confiscation on Farmers in Myanmar

The negative effects of the land seizures seeped into other aspects of farmers’ lives, limiting their ability to access health care and to provide education for their children, many of whom were forced to leave school and go to work. Many in Myanmar who lost their lands resorted to working as manual laborers, making only a few thousand Myanmar Kyat (a couple of US dollars) per day.

Since the transition from the military government to a quasi-civilian-led government in 2011, the authorities have sought to address the issue of land confiscations. Former President Thein Sein instituted multiple reforms, including the passage of the Farmland Law and the Virgin, Fallow, Vacant Management Law, and the adoption of the National Land Use Policy and an investigation commission to investigate claims of confiscated land. However, by the time the newly elected National League for Democracy-led government took office in 2016, many thousands of confiscated land claims remained unresolved.

In fact, a central plank of the National League for Democracy’s manifesto was to end the pernicious effects of mass land confiscations carried out under military rule. The new government took important steps by forming another investigative body and undertaking reforms of critical laws. Still, despite some limited successes, many farmers have not seen any results.

Most of the farmers with whom Human Rights Watch spoke said they had filed claims for years, without receiving any response. Many blamed the failure of reforms on corruption and incompetence. Hundreds of farmers across Myanmar, fed up waiting for the return of their lands or receiving compensation, have been prosecuted for organizing and participating in public protests against the government or for trespassing by farming the land they claim. Those criminally charged often endure lengthy trials, creating new financial burdens.

Human Rights Watch calls on Myanmar’s government to stop arbitrarily arresting land rights activists, and immediately release all those who are awaiting trial for peacefully protesting land seizures. The government should also impartially investigate allegations of unlawful land confiscation, publicly report the findings, appropriately prosecute those responsible for land rights abuses, and provide prompt and adequate compensation to farmers and others who have been unlawfully deprived of their land.

“Donor governments shouldn’t be fooled by the flurry of proclaimed land reforms in Myanmar,” Robertson said. “The Myanmar government needs to provide redress for victims of past unlawful confiscations and ensure that new laws safeguard the rights of farm families in the future.”

This report is accompanied by photographs taken by award-winning photographer Patrick Brown. Brown traveled with Human Rights Watch to Shan State, Ayeyarwady and Yangon regions. Brown’s work will be on display at Pansuriya Gallery in downtown Yangon following the release of “Nothing for Our Land.”