Thailand’s proximity to China and Vietnam, the world’s two primary markets for pangolins, combined with its well-developed transportation infrastructure, have attracted criminal syndicates specializing in illegal wildlife trade to take root here.

In the early hours of a Sunday morning this past March, officers manning a roadside checkpoint in Thailand’s Prachuap Khiri Khan province were hardly fooled when an approaching pick-up attempted to bypass their blockade by hastily detouring down a side road 300m away.

The officers gave chase and pulled the vehicle over. Its load of construction materials appeared innocuous enough, but no stack of lumber could disguise the odd odor. It did not take the officers long to uncover 18 net sacks containing 76 live pangolins, among the most illegally traded endangered mammal species on the planet.

The driver, Sompol Mekchai, confessed that this shipment, valued at more than US$300,000, was his third job trafficking within Thailand these shy, insect-eating, scaly animals playfully described by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as resembling artichokes with legs and tails.

Sompol was paid 8,000 baht (US$260) to transit the pangolins just 320 km of a planned 4,000 km journey that began with their poaching in Indonesia and was to terminate in China where traditional Chinese medicine places great value on the supposed healing powers of pangolin scales and their meat is considered a dining delicacy.

Sompol’s arrest came with mixed feelings to Pol.Lt.Col. Adtapon Sudsai of the Royal Thai Police’s Natural Resources and Environmental Crime Suppression Division (NED). After nearly a decade of fighting wildlife crime under his division’s commander Pol.Maj.Gen. Panya Pinsuk, a little luck had landed them another bit player that day, but Adtapon suspected Sompol would likely be back on the road soon.

Indeed, though Sompol could have faced up to four years in prison for trafficking endangers species, he was released after paying a 40,000 baht (US$1,3000) fine as prosecutors claimed Sompol was not directly involved in the pangolins’ sale.

Worse still, the arrest brought no new information to help Adtapon strengthen cases against any of the handful of Thai-based ring-leaders who have facilitated the epic growth of the global pangolin trade, plummeting the populations of all eight of the world’s pangolin species, two near extinction.

Thailand’s axis of extinction

Adtapon’s frustrations are widespread. The United Nations, many western countries, and leading international NGOs, especially the Bangkok-based Freeland Foundation, have longtime been assisting Thailand to overcome law-enforcement challenges that have allowed Thailand to become a major hub for what is now a US$20 billion wildlife trafficking industry.

The illegal trade in pangolins represents a significant part of this market. An estimated 20 tons are trafficked annually, captured from their native habitats in Africa, Malaysia and Indonesia, with the vast majority of the victims, or just their scales, delivered to customers in China and Vietnam.

Thailand’s proximity to these markets, combined with its well-developed transportation infrastructure have attracted criminal syndicates to take root here. As USAID’s Wildlife Asia program notes, “Many shipments of rhino horn, elephant ivory and pangolin carcasses and scales have been seized in Thailand, especially at the Bangkok Suvarnabhumi International Airport. While these high-profile seizures are to be commended, the criminals involved often walk away unpunished.”

One of the most slippery kingpins, asserts Petcharat Sangchai, director of Freeland-Thailand, is Daoruang Kongpitak, a 43 year-old Thai-Vietnamese woman they have been tracking for more than a decade. She has been operating a commercial tiger zoo in Chaiyaphum province, about halfway between Bangkok and Laos, believed to be a major transit point for wildlife smugglers. Her facility was raided in 2010. In 2014 assets totaling some 200 million baht (US$6.5 million) were seized, but were returned on appeal two years later.

“We always found ourselves one-step behind,” Petcharat says. “The network has frequently changed tactics and financial routes to avoid legal punishment. Closer cooperation from neighboring countries are crucial as the network involves crime agents in Thailand, Laos and Vietnam,” he adds.

Adtapon notes, without specifically naming a suspect, that he has been tracking a Thai-Vietnamese woman operating in Thailand who he believes has amassed a fortune through illegal wildlife trade. She utilizes strong connections with both Vietnam-based family members believed to be leading a wildlife trafficking network there, and senior officials here in Thailand who may be assisting her maintain her illegal enterprise says Adtapon.

Adtapon adds that she works with China’s top pangolin traders. They often transfer money to her in advance, through multiple Thai bank accounts in the names of her Thai-based family members. Their deposits are kept below two million baht (US$ 64,516 for each transaction to escape reporting regulations mandated by the Bank of Thailand.

It’s widely acknowledged by Adtapon’s investigative team, that she has a key partner in Songkhla province. Known as Bang Yee, this accomplice has solid connections with poaching groups in both Indonesia and Malaysia and has now established himself as a primary coordinator for trafficking wildlife from these countries into Thailand with onward transit to Laos.

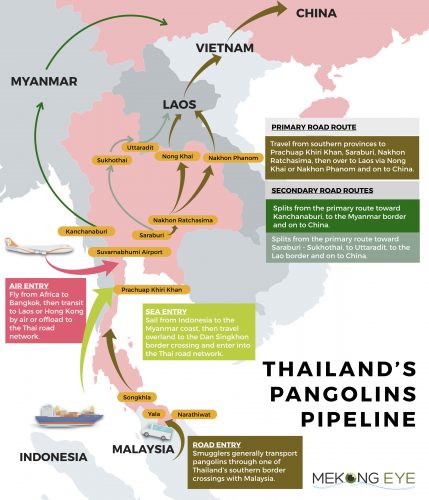

His preferred pangolin smuggling route through Thailand, says Adtapon, begins in the southern gulf province of Songkhla, where the animals arrive by either boat or road from Malaysia. They are then driven 1,600km north to Nong Khai, a city along the Mekong River just opposite the suburbs of the Lao capital, Vientiane.

Adtapon estimates that approximately one million Thai baht (USD 32,400) is charged to deliver each shipment from Thailand’s southern border with Malaysia to the banks of the Mekong River, at which point Lao and Chinese traffickers take over to complete their journey to China.

The price, according to Adtapon, of live pangolins seized from its native habitat is approximately 500 baht/kg (US$16.20. The price jumps six-fold by the time they reach Laos and increases to 4,000 baht/kg once they arrive in Chinese markets. Dead pangolins are worth far less, just 1,000 baht/kg in China.

“The return is very high, so an arrest doesn’t mean much to their profit, especially when the arrest rate is very low. Arrests do drive up their costs, which are about 400,000 baht (US$13,000) per shipment, but this illegal business is nonetheless attractive,” Adtapon says.

Race to the border

To ensure the pangolins reach the Lao border alive, efforts are made to keep their transit time in Thailand under 24 hours. Drivers typically stop just twice for fuel and to provide water to their illegal cargo. Small gasoline stations in Chumporn in the South and Nakhon Ratchasima in the Northeast are their main service points.

The only information drivers have is a disposable-phone number and the pick-up and drop-off locations for the transit segments they are responsible for.

Previously, hundreds of animals might be contained in a single shipment, but as authorities stepped-up their searches, the traffickers responded.

Now, highly modified cars are often used, which provide dedicated spaces to conceal the pangolins. While these vehicles can carry only 40 to 50 pangolins, they are far more effective at evading detection says Adtapon, adding that this has only put more smuggling vehicles on the road and has had no impact on the number animals transported over time.

Further, says Adtapon, drivers are typically not out there alone as appeared to be the case with Sompol. Advanced teams are used to inform drivers about unplanned checkpoints as well as other road hazards that could impede their travel. Additionally, back-up teams are ready to provide assistance if a driver does encounter trouble, including engaging police to create a diversion to allow the driver to escape potential capture.

A source with the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, who requested anonymity as they are not authorized to speak with the media, says the majority of live pangolins entering Thailand come from Indonesia. They pass through one of three Thailand/Malaysia border crossings: Sadao in Songkhla, Betong in Yala, Sungai Kolok in Narathiwat province, the source says.

“For this (Sompol’s) case, however, we suspect that the pangolins were shipped from Indonesia by a trawler, (arrived the Myanmar coast) then entered Thailand at Dan Singkhon checkpoint in Prachuap Khiri Khan province, before going to the destination,” the source adds.

The source further speculates that pangolin smugglers may also be using roads heading west toward Thailand’s border region with Myanmar, as opposed to northeast to Laos, then onward to China. A police team captured a pangolin smuggling gang in Kanchanaburi province a few years ago that was suspected of using such a route.

A source stationed at the Dan Singkhon border crossing in Prachaup Khiri Khan province, who also requested anonymity. said while there is no record of arrests at this crossing into Myanmar, this by no means indicates that pangolin traffickers are not using this route.

Scales in the air

About 20 percent of a pangolin’s weight is contained in its thick, protective scale made of keratin, the same material as human fingernails. When threatened, pangolins curl into a ball, using the scales as armor to defend against predators.

Traditional Chinese medicine practitioners believe this armor can treat a variety of human ailments. Some 200 Chinese pharmaceutical companies produce some 60 types of traditional medicines that contain pangolin scales, contributing greatly to the rise in pangolin trafficking.

Dried pangolin scales are far easier to transport and much harder to detect than live pangolins. They fetch an even higher price, at upward of 40,000 baht (US$ 1,250)/kg. African traders have emerged as a major source, especially since China’s President Xi Jinping announced a ban on domestic sales of ivory in 2017, causing wildlife smugglers to turn increasingly to beleaguered pangolins, since they can be legally sold in both China and Vietnam.

Chaiyut Kumkun, a spokesperson for Thailand’s Department of Customs, explains that commercial airlines are the preferred mode of transport for African pangolin scales. They generally originate from Nigeria and the Congo, and often transit through Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi airport, though Hong Kong and Vietnam seem to be the biggest destination ports.

From 2013 through mid 2016, Thai custom officials intercepted five pangolin shipments at Suvarnabhumi Airport that combined were valued at six million baht (USD195,000). Then in December 2016, they seized two shipments totaling 2,900 kg valued at 116 million baht (US$3.76 million). The contraband was shipped from the Congo, smuggled through Turkey and eventually bound for Laos—a key transit hub for regional trafficking syndicates. At least 6,000 pangolins would have to be killed to gather 2.9 tonnes of scales.

“We have been aware that pangolins are a top concern within the international community so have been closely working with both domestic and international partners to detect illegal shipments. Fortunately, we have seen a declining number of illegal pangolin imports via Suvarnabhumi to the country,” Chaiyut says.

He suspects the department’s installation of 1,647 CCTV cameras at its Suvarnabhumi facilities, along with more x-ray machines to scan cargo, along with increased deployment of cargo e-tracking systems have collectively worked to deter smugglers from using Suvarnabhumi.

The apparent success at Suvarnabhumi is certainly a positive sign he says, but adds that Thailand is a long way from shutting down its pangolin trafficking infrastructure.

“Wildlife trafficking is a transboundary issue and we are in the middle. We have tried our best to scale down the problem by blocking the illegal trade as much as possible. But full achievement can’t be reached until we can get cooperation from all stakeholders,” Chaiyut says.