“To control and reduce vulnerability to climate change – as well as to the overexploitation by human activity – policies, legislation and other supporting tools should be developed by government agencies in a coordinated manner when enacting norms and regulations,” U Myint Thein suggests.

Meanwhile, farmers in need of a quick fix and engineers concerned about the safety of coastal communities are calling for protective polders that can be used to reduce flooding and allow for seasonal planting.

Polders are low-lying tracts of land that have been reclaimed from the sea and are surrounded by dikes that create boundaries where the water may be drained off through tide gates and automatically closed to prevent re-entry of seawater at high tide. The land surface here suffers less saltwater intrusion and allows freshwater to recharge the aquifer. Therefore, even though the groundwater cannot be used for domestic purposes, farmers can still use the land to grow rice paddy and create a reservoir to store rainwater.

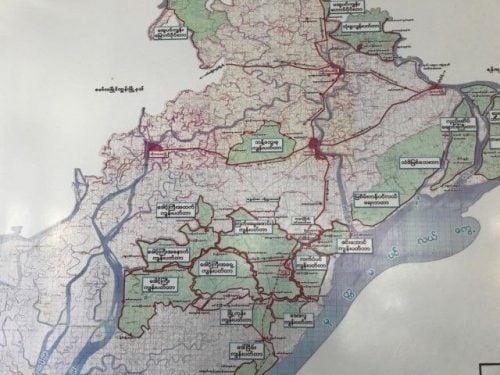

Polders created in Pyapon and Bogale townships in the lower Ayeyarwady delta region by the Paddy I Project, initiated by the World Bank from 1976 to 1985, for many years helped reclaim abandoned paddy land in lower Myanmar. The project has helped to reduce flooding, control freshwater and allow for seasonal planting.

But the polders need to be built higher in order to prepare for climate change and protect against extreme cases like Cyclone Nargis, according to local engineers. That cyclone destroyed over 23,000 hectares (ha) of paddy fields in 2008, causing over 100,000 fatalities in the Ayeyarwady Delta.

“Even though we have polders and dikes, we still need to be careful about extreme weather cases, like Nargis,” said U Thein Zaw, a senior engineer from the irrigation and water utilization management department (IWUMD) of Pyapone township. “To protect against these future incidents, the height of the polder needs to be built higher.”

In 2008, seawater levels rose to 12 feet during the cyclone, overcoming the existing height of the polders, which are around 8.5 feet high. U Thein suggested that in order to handle future extreme scenarios, the polders need to be raised to be higher than 12 feet.

Currently, the polders are being upgraded and funded by JICA (the Japan International Cooperation Agency) together with IWUMD, U Thein said.

“Once the seawater enters the polder area, it is difficult to get the freshwater around those affected places. Therefore, it is better to prevent natural disaster and be prepared,” he added.

Due to expected temperature rise, which reduces the amount of groundwater recharge, coupled with rising sea levels, the Pyapone area could experience increased flood levels in the future, U Myint Thein, the hydrogeologist, explained in a research paper on the climate change threat to groundwater in Myanmar. To anticipate climate change in the Ayeyarwady Delta this century, the height of sea level needs to be added into the existing design crest level of the height of the polders.

| Timeline | Middle range of projected sea-level rise (cm) |

| 2020s | 5-13 |

| 2050s | 20-41 |

| 2080s | 37-83 |

FARMERS IN A BIND

“Unlike Pyapone township and [its] surrounding villages, we have no polder around Amar township and the southernmost part of Pyapone Region,” said U Zaw Win, a representative of the farmers of Bawa Thit Village.

In Amar township, which is located in the coastal area of the lower Ayeyarwady delta, locals already struggle to get freshwater for cooking and bathing. Due to climate change, the effect is expected to only increase in the coming years.

An initial assessment of climate change for the national Myanmar Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (MCCSAP), stated that globally sea levels are projected to rise by 0.26-0.82 meters by 2100; regionally that level is predicted to rise by another 10 percent.

U Zaw Win, the representative of the farmers of Bawa Thit Village / Credit: Kyaw Nyunt Linn

“Every year we are struggling with keeping the freshwater for growing the paddy fields,” said U Saw Mu Lei, a 57-year-old farmer who lives in Amar Township.

As the groundwater has become saltier, farmers are forced to rely on rain as their main source of freshwater.

“This is essential not only for farming but also for storing the drinking water,” U Saw said.

During the dry season or when rains don’t come, growing paddy becomes impossible. “We can only do farming during the monsoon season,” U Saw said. Water under the ground cannot be used for irrigation purposes as there has been saltwater intruding to the underground aquifers. U Saw said his ability to farm depends on cloudy skies, which give him freshwater for growing.

But waiting for freshwater from the sky is inadequate in the long term.

“Once the rain is delayed, it can damage the whole process. We cannot get a certain price while selling our paddy,” said U Saw. The rain is the hero, helping farmers by providing freshwater for domestic uses, a dependable savior of Amar. Yet, due to climate change, it becomes more abnormal than the usual.

Based on Myanmar Climate Report 2017 published by the Norwegian Meteorological Institute & Department of Meteorology and Hydrology, the normal duration of the monsoon period was 144 days on average between 1961-1990 but just 121 days from 1981-2010.

UNUSUAL RAINFALL AND SALTWATER

It is hard to connect climate change directly to any individual weather events, such as heat waves, cold snaps, droughts, extreme rainfall or severe storms. But climate change is happening, and farmers say over time the weather has become more extreme and less certain.

Freshwater from the rain can relieve the saltwater intrusion under the ground, allowing paddy and other plants to grow during monsoon season. Normally it takes around seven to nine days for rains to leach out the salt, based on local farmers’ comments. So, this battle between freshwater and saltwater happens both on the surface and underground.

Yet the changes in weather patterns makes predicting rainfall more difficult. In Amar, farmers who depend on the rain say they have seen more damage to their livelihoods over the last 10 years.

“Here in Amar, we cannot start to grow the paddies without getting rain as the saltwater exists on the surface of the ground more and more,” said U Zaw Win, the representative of the farmers of Bawa Thit Village.

“Normally, the rain starts on the first week of May but this year, in 2019, it started on the third week of May which can affect the supplementary process of cultivating the paddies,” he said.,

While rain is good, U Zaw said too much rain at once can also cause big problems.

“During the heavy rain event, the freshwater coming down from the Ayeyarwady River spills out to our paddy fields. Even though it is freshwater, it floods to our paddy fields,” he said.

“Due to unusual rainfall patterns and saltwater intrusion, the production process of paddy rice is getting damaged compared to last 10 years,” U Zaw added.

Normally the soil is prepared for planting at the end of May and the seeds are sown the first week of June, but in recent years the timing has become delayed.

“The interruption in harvesting process can [impact] the quality of rice,” U Zaw said. “When we sell it, the price is lower than the usual.”

In Amar township, generally farmers can yield at most 50 baskets of rice per acre during the monsoon season. In Pyapone township, which is located around 87.2 kilometers from Amar, the average yield for rainfed paddy in the wet season is between 57-73 baskets per acre, according to a mission report on the current status of the polder in Pyapon township developed by the Consortium Welthungerhilfe (WHH) and GRET.

Myanmar’s economy and society are still largely dependent on agriculture and the changes in climate, therefore, have a heavy impact on this important sector. Myanmar Climate Change Alliance stated that from July to October 2011, heavy rain and flooding in the Ayeyarwady, Bago, Mon and Rakhine Regions/States resulted in losses of approximately 1.7 million tons of rice in demonstration of the impact of climate change.

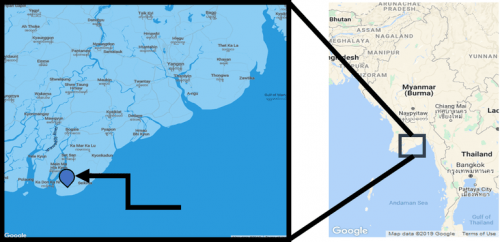

Amar Township, the southernmost part of the lower Ayeyarwady delta region / Credit: Google Maps

MOVING OUT OF SUFFERANCE

Local indigenous farmers struggle in these extreme situations, with some being unable to continue planting. Saltwater intrusion usually gives farmers difficulties in the agricultural cycle of debt, harvest and repayment since lower yields and incomes make it harder to pay back loans.

“Some of the local farmers move to the new place to settle the new lives. Their lands are corrupted year after year and they cannot continue their lives by doing irrigation,” said U Zaw Win.

“Two out of 10 of farmers had migrated to Bago and Myeik where more job opportunities such as carpenters and general workers can be found by receiving regular money to survive,” he added.

“If people have enough money, they can build a polder around their paddy fields by themselves. But still we do not have a main polder which can protect our surrounding paddy fields,” U Zaw Win stated. “Due to the lack of these polders, we cannot create a reservoir near our township to store the rainwater for the dry season,” he explained. Hence, 555 households and 2,200 locals are still struggling to get drinking water as well as freshwater for irrigation purposes.

An engineer from the irrigation department confirmed that it had done a survey, but when thinking about where to direct finances to implement a polder project, the area around Amar Township was not a first priority.

MITIGATION PLAN OF GROUNDWATER

U Myint Thein says salty grounds cannot transform to fertile grounds overnight – it is a timely process.

“It took a decade to recharge the freshwater to the underground reservoirs. Because rainwater is the only way to recharge the underground reservoirs,” he said.

The temperature and quantity of groundwater are correlated to each other as groundwater aquifers are recharged mainly by rainfall but hampered by temperature. The higher the temperature, the more the rainwater evaporates, lowering the groundwater recharge rate.

On the other hand, as the overexploitation of groundwater alongside the coastal area can also affect saltwater intrusion into the aquifers, human activities such as digging tube wells without any stringent restrictions can cause more salinization than usual.

To ensure Yangon and other urban areas can still use groundwater, U Myint Thein suggested that “for local communities, rather than preventing them from digging tube wells, we need to show which is the best way to create tube well effectively by consulting with technicians, working as a community or township together.”

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.