As dingy haze overcomes much of Thailand this month, many fear a return this winter to the noxious conditions that brought international headlines earlier this year of Thai cities leading the world’s hazardous breathing indices—and experts concur.

For years, Kanyarat Chaksuwong, her husband and their three-year-old son have commuted by motorcycle 60 kilometers round-trip from their home in Samutsakorn province to their jobs in Nakon Pathom.

“We’ve known that the dust and traffic fumes are toxic and getting worse, but we have to work every day,” Kanyarat explains.

She suggests that anyone who thinks the government has been genuine in following through with its proclamations to target some of the key sources join the trio on their commute.

“It’s not just the disgusting exhaust we still have to breathe that’s pouring out of old cars, trucks and busses, but the black clouds coming out of factories that is unchanged too. I feel burning sensations in my nostrils every time we pass through the area,” she describes.

While the government has given sporadic attention to removing ‘black smoke’ vehicles from some roadways, Kanyarat observes, these efforts have not been sustained. Moreover, there’s been no commitment to addressing the problem at its source, with another 180,000 new vehicles registered in Bangkok in just the first two month of 2019 alone.

Likewise, while local governments attempt to implement a ban on outdoor burning, national agricultural policies continue to promote the expansion of farming industries that rely on it. Two million rai (320,000 hectares) of corn crops were added to Thailand’s agricultural sector between November 2018 to February 2019, likely to become fields of fire after every harvest.

No political will, so no reform

Dr. Supat Wangwongwattana, former director general of the Pollution Control Department and now a lecturer on public health at Thammasat University, says the case study of vehicle exhausts highlights the historical momentum impeding air quality reform.

Dirty exhaust from incomplete combustion has longtime been known to be the major source of PM2.5 pollutants in Bangkok. Correspondingly, stringent emission control standards have regularly been brought forward as a major strategy to improve the region’s air quality.

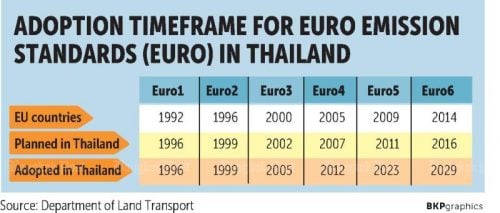

Dr. Supat cites feeble efforts to phasing down sulfur in transport fuels to not more than 10 mg/m3 (equal to EURO 5 emission standard) as just one example. “The implementation has been delayed for 13 years from our first scheduled date,” he recalls. “Some entrepreneurs didn’t want to make new investments, so they lobbied the government to postpone the plan until ‘they were ready’.”

The implementation of EURO 5 emission standards, which have been in place in South Korea for a decade, remains a long, turbulent road in Thailand. Only last year, after three years of negotiation, did oil refiners agree to comply, and then it took granting them a five-year grace period. Meanwhile, Singapore is two years into implementing EURO 6 standards.

“Compliance should have started in 2022, however, as of now there is still no resolution from the National Environment Board acknowledging a mandatory upgrade,” the former pollution control technocrat explains.

Dr. Supat doubts recent media reports that EURO 5 standards may be implemented sooner. “At the end of the day, it’s up to the political will of those lawmakers. They have to bang on the table and send orders down to the operating levels to start doing something,” he stresses. “Since we are not taking it [pollution] seriously, it will come again at the end of this year, and reoccur every year thereafter.”

Delay, delay, delay

There is a consensus among many academics that the key weapon to reduce smog is to implement more stringent regulations on the discharge of harmful gases from their sources of origin.

“When you don’t tackle the problem at its root, it’s expensive to regulate, and too easy for polluters to dodge their responsibilities. Polluters must pay,” stresses Dr. Supat.

Therefore, the strengthening of Thailand’s allowable PM2.5 levels from cars, factories, refiners and open-field burning must be a top priority, he adds. Once again, however, complaints from the private sector about investment costs and economic losses have prompted the National Environment Board to delay any changes.

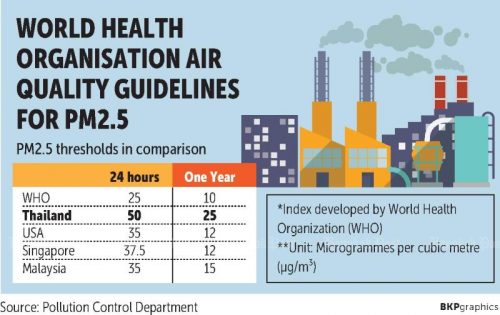

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that while there is no evidence of a safe level of air pollution exposure, nor a threshold below which adverse health effects will not occur, it has established thresholds for six pollutants. Among those receiving the greatest attention in Thailand is PM2.5 – the concentration of particulates in the air of sizes less than 2.5 micrometers. The WHO guidelines state that a person’s average annual PM2.5 exposure should not exceed, on average, 10 micrograms per cubic meter (mg/m3), and that exposures during any 24 hour period should not exceed 25 mg/m3.

Presently, Thailand considers 50 mg/m3 an acceptable level of PM2.5 exposure for people during a 24-hour period, and 25 mg/m3 as an acceptable average level of exposure over the course of one year. The country’s average concentration of PM2.5 from 2011-2018 was 24 mg/m3, with Bangkok and the surrounding areas closer to 30 mg/m3.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sirima Panyamethikul, Chulalongkorn University’s Department of Environmental Engineering, who leads the Thailand Network Center on Air Quality Management (TAQM), reiterates the need for stricter standards here.

“By now, the Pollution Control Department should have reduced the allowable concentration of PM2.5. With Thailand’s average annual levels below 30 mg/m3, we should be able to tighten our standard from 50 down to 35, which is the same level as the United States. And the next goal should equal the World Health Organization’s 25 mg/m3 standard,” the environmental engineer says.

Dr. Sirima notes that the National Environment Board insists such revisions are unnecessary, recently stating that the nation’s “sustainable transportation system” will soon be in place. The Board also claims that insufficient data exists to justify such a move, and more data should be gathered for another 6-7 years, during which time Thailand’s PM2.5 levels will fall. Therefore, new regulations won’t be needed, which could effect key economic sectors.

Such inaction is unacceptable says Dr. Sirima. The Pollution Control Department is obligated to revise and improve the national air quality standards every five years, but has done nothing since first enacting them in 2010. Furthermore, WHO guidelines also specify governments regularly pursue more stringent measures for their National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

Dr. Sirima also recommends cooperation across government agencies to establish emission control standards from sources of origin and to better enforce existing pollution control regulations. “We should pursue a common goal in protecting the health of Thais. It does not mean we must do everything at once right now, but we have to have a goal.”

Ignoring attention to environment and health

If one needs evidence of the government’s disinterest in environmental quality, just look at the lack of money says Dr. Witsanu Attavanich from Kasetsart University’s Economic Faculty.

“The [budget] numbers clearly show that environment protection is not a government priority,” Dr Witsanu observes. “They focus only on economic stability and growth. In the government’s expenditure budget from 2015 to 2019, economic-related expenditures rank second after administrative expenses, whereas the budget set aside for environmental protection is extremely small.”

For the 2019 fiscal year, Thailand’s environmental expenditure budget is Bt10.9 billion. This is 0.4 percent of Thailand’s total budget of Bt3.1 trillion, or just 0.05 percent of Thailand’s GDP. This is half the percentage allocated toward environmental protection in South America, 13 times less than the percentage allocated by the People’s Republic of China and 14 times less than the European Union.

“Air pollution levels have remained dangerously high in recent years, and do not seem to be improving. It is because we focus only on economic development and pay less attention to environmental protection and conservation. Certainly, the economy has clearly improved, but the question is, is it sustainable?” Dr. Witsanu asks.

He points out that the economic costs associated with declining air quality is widely known. For example a 2017 World Bank study found that air pollution was a factor in one in ten deaths globally, and that for Thailand, the economic costs of air pollution quadrupled from Bt211 billion in 1990 to Bt871 billion in 2013.

Air Quality Life Index ranks Thailand as the world’s seventh-most polluted country, with poor air quality reducing averages life expectancies here by two years. Residents in and around Chiang Mai should expect about a four-year reduction.

In less than a generation, Thailand has moved from a low-income to an upper-income country. “So in economic terms, we must not only think about efficiency of resource management,” argues Dr. Witsanu. “We should shift our attention to environment and not forget that our decisions today will effect the next generation and also bring fairness into the equation every step of the way.”

Planners should listen to the people

Thailand’s current National Economic and Social Development Plan (2018 – 2022) contains phrasing that suggests attention to environmental challenges: preserve and restore the natural resource base; clean up pollution; efficiently manage water resources and foster green growth. However, former Pollution Control Department director Dr. Supat argues that the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) will have trouble integrating these goals into a longstanding culture committed to GDP growth metrics.

The agency’s focus, says Dr. Supat, largely remains advancing 20th century development strategies. It aims for a five percent annual growth in GDP with the hope of Thailand reaching an economic level consistent with the world’s high income countries.

Embedded within this target says Jinanggoon Rojananan, NESDC senior advisor, is shifting the Thai economy toward “green growth and to not destroy the environment.” However, she concedes there is still a gap in the agency’s incorporation of resolving natural resources challenges into its objectives, though a new collaboration unit has been set up within the government to facilitate integration of green economy concepts into development projects.

Asst. Prof. Dr. Surat Bualert, Dean of the Environment Faculty at Kasetsart University, fears NESDC’s efforts, while well meaning, are seemingly too little too late and don’t reflect where Thailand needs to go. “Without incorporating the importance of the natural environment [into development policy] now, we will not be able to change the mindsets of both the older and younger generations to think about health and societal wellbeing along with economic sustainability in the long run.”

Mira Chaimahawong, a Bangkok educator and mother of two, agrees. She feels that unless something changes, there’s little reason to expect air quality to improve.

She has taught her own children to use public transit to increase their awareness and to minimize their own impacts. “I know commuting by mass transit is more difficult, however, my kids want to try. They understand the problem and want to make a difference.

”For now, we should at least prepare our kids to be ready for this era of toxic smog. We will face more pollution as well as other environmental problems, so our children must learn to protect and adapt themselves to be able to deal with rising pollution,” Mira suggests.

It’s precisely such views and attitudes that must be reflected in our development plans, adds Dr. Surat, otherwise he fears future Bangkok residents will not be able to live in a clean, safe environment.

“Most of all, Thais must be able to take part in determining their own future as it [a national strategy] should not be in the hands of a few people in the government. When we realize this point, we can see the hope of a better future,” says the environment lecturer.

—

This Mekong Eye report is the first of two-parts examining the structural impediments to resolving Thailand’s evolving air pollution crisis. Versions of this report also appear in the Bangkok Post and Manager online (Thai language). Reporting was supported Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.