This is the first story in a three-part Mekong Eye feature report exploring how contract farming in Myanmar’s Shan State is leaving poor farmers buried in debt and people in neighboring countries choking under smog. (read part 2) (read part 3)

It was a chilly but sunny December morning when our team of environmental journalists arrived at Tha Yat Pin Hla Village, a small farming community in south Shan State on Myanmar’s eastern border. Faint mist was fading as the sun rose in the blue sky, revealing golden fields of ripe maize extending over rolling hills as far as the eye could see.

However, local maize farmer Re Jin told us that within months this scenic beauty would change beyond recognition – scorched by fire to leave only blackened empty fields.

Clouds of smoke from the burning would pollute the air, triggering the season’s regionwide smog crisis.

“After harvesting, many maize farmers choose to burn their fields during dry season months to clear the stalks, as this is the cheapest and most convenient method to prepare the land for the new growing season,” Re Jin said.

“We actually prefer not to burn the fields … because we are affected by pollution from the burning too. However, for many smallholder maize farmers, fire is the only affordable option.”

Maize brokers promise farmers large incomes in return for growing maize under contract, but most contract farmers see little of that profit because their production costs are high and the price of maize is falling fast, he said.

Contract farmers need to purchase maize seeds from brokers every season. They must also bear the cost of fertiliser, herbicide and pesticide, without which maize will not grow, said Re Jin.

“So, many farmers have to borrow from the broker to cover these expenses.”

Moreover, a recent drop in demand from Chinese buyers had seen the price of maize plummet to 340-380 kyat (US$0.25) per viss (1.6 kilograms), cutting the income of farmers still further, he said.

According to World Bank figures, producing maize in southern Shan State costs about US$104 per acre. The cost of raw materials accounts for up to 30 percent or US$35 of that total.

This financial burden has trapped many local farmers in a cycle of debt, said Re Jin, as the profit from selling their maize is not enough to repay the loans they take to cover production costs.

“Unless the government or other stakeholders offer measures to relieve financial pressure on maize farmers in the contract system, the burning will continue,” he concluded.

Burning of maize fields in Shan State has expanded over the past few years, causing transboundary haze. Photo by: Visarut Sankham

Industrial maize farming fueling the problem

Transboundary haze is not a new problem in the Mekong Subregion. Almost every year during the dry summer months, the skies over Shan State and neighbouring northern Thailand and Laos turn grey with dense smog.

But the severity of seasonal haze has grown in the past two years.

A recent study by Chiang Mai University’s Climate Change Data Centre (CCDC) shows the northern smog seasons in 2019 and 2020 lasted longer and were harsher than in previous years, with transboundary haze seen as early as January.

The situation was so severe that levels of hazardous PM2.5 particles soared to 700-1,000 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3) – up to 40 times the World Health Organisation’s safe limit of 25μg/m3.

The Mekong Subregion’s serious transboundary haze problem is closely linked to the increase in local maize production, said Asst Prof Arisara Charoenpanyanet, a lecturer in Chiang Mai University’s Geography Department who led the study on “Maize, Land Use Change, and Transboundary Haze Pollution”.

The study showed the proportion of burnt maize fields in northern Thailand, northern Laos, and Shan State surged almost 10 percent in five years – from 14.7 percent in 2015 to 24.4 percent in 2019.

These figures indicate ongoing expansion of monoculture maize farming in Shan State, northern Thailand and Laos, and also help explain a sudden spike in burning in 2019.

“From 2015-2018 the number of observed hotspots on maize plantations in the Mekong Subregion was relatively stable at around 25,000, but in 2019 the hotspot count doubled to 51,962,” said Arisara.

The study also found the area of burnt maize fields in the region was increasing every year, from 124,800 hectares in 2015 to 168,000 hectares in 2019.

Laos saw the highest rise, at 41 pecent over the past five years, but Myanmar had the largest area with 2.245 million rai of burnt fields in Shan State alone in 2019.

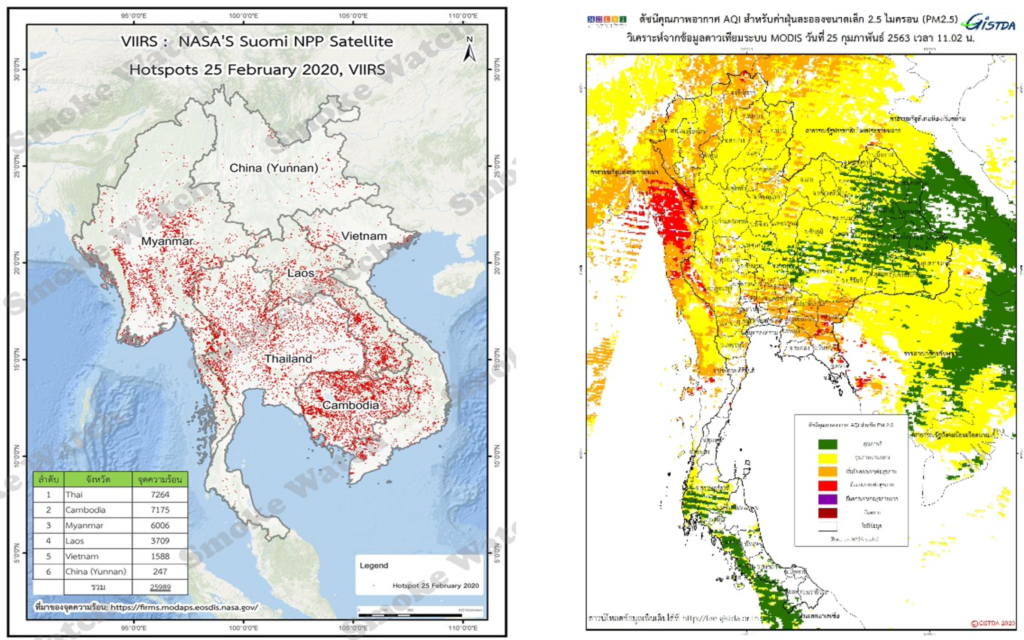

“If we look at satellite maps of hotspots and PM2.5 haze during this year’s dry season in the Mekong Subregion, we see that burning of distant maize plantations across the border is clearly linked with hazardous haze across the region, with PM2.5 levels measuring over 800μg/m3 in some areas,” Arisara said.

February 2020 satellite data of maize hotspots (left) and transboundary haze (right) recorded by the Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (GISTDA) and United States’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

A NASA satellite map of the Mekong Region on February 25, 2020 shows approximately 20,000 hotspots in dense clusters.

A GISTDA satellite map of air quality on the same day reveals a dramatic rise in PM2.5 levels across the region, especially across Thailand and western Myanmar.

March 2020 NASA satellite image shows the Mekong Subregion veiled in thick PM2.5 smog.

Associate Professor Witsanu Attavanich from Kasetsart University’s Economics Faculty stressed that seasonal transboundary haze is among the most urgent environmental and health problems for every country in the region. This was because the dense smog not only disrupts people’s daily lives and businesses, but also threatens their health and wellbeing.

The haze is not just smoke, he explained. It is actually composed of ultra-fine particles smaller than 2.5 microns (PM2.5) and other hazardous pollutants which can cause asthma, respiratory diseases, stroke or even lung cancer.

“Smog from remote burning activities is a major source of air pollution, since it can be carried by the wind over long distances regardless of national borders. Hence the pollution from burning maize farms in neighbouring countries can also affect us living in Thailand,” he said.

Business, local authorities scramble to clear the air

While concern about the health impacts of burning is growing among locals and experts in Thailand, Shan State authorities say there is not yet clear evidence that seasonal haze is causing widespread sickness in the area.

“We have no data on sickness caused by air pollution yet, but this year we are developing a system to gather information on people’s health during the haze season,” said Dr Nang Seng Zin of Shan State’s Ministry for Health and Sport.

“At the same time, we are trying to educate people on how to protect themselves against air pollution and alert them via radio and television when it spikes.”

Poor smallholder maize farmers in Shan State are forced to burn maize fields, despite being the ones most affected by PM2.5 smog. Photo by: Visarut Sankham

U Lay Naing, director of the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration, said agricultural investment is considered to be the economic lifeblood of Shan State.

As transnational food companies and authorities promote more maize farming in Myanmar, he has insisted that their investments follow local laws and regulations if the environment and health of local people are to be protected.

The largest maize-for-animal-feed investor in Myanmar is Charoen Pokphand (CP), a Thai multinational.

Worasit Sittivichai, executive vice president of CP Myanmar, said the company promotes best practices across its entire maize production supply chain, but also acknowledges the clear link between burning on maize farms and transboundary haze.

He said that CP is now working with local authorities to solve these problems, as part of its more than 20-year-long investment to build Myanmar’s local economies.

CP does not engage with maize farmers directly, only providing them with seeds and other farming materials, and then purchasing maize via local brokers, Worasit explained.

“But we are encouraging the farmers in our network to avoid burning their maize fields and instead use tractors to plough in the stalks,” he said.

“We have even started a CSR project in Shan State to promote sustainable maize farming locally. By introducing environmentally friendly techniques such as microorganisms to break down maize stubble, we help farmers avoid burning, while also improving their soil fertility.”

Animal feed industry investment in Myanmar has resulted in massive monoculture maize plantations in Shan State. Photo by: Visarut Sankham

Cooperation necessary to break smog cycle

While acknowledging CP’s efforts to tackle transboundary haze at the local level, Greenpeace Southeast Asia said they were not a sustainable solution.

“The major obstacle to ending the transboundary haze problem in ASEAN is that governments lack a regional approach to tackle it seriously, as most countries are focused on national issues,” explained Tara Buakamsri, Thailand country director for Greenpeace Southeast Asia.

“This situation allows the business sector to ignore sustainable solutions to the problem, such as providing data or partnering with state agencies to plan strategies for tackling transboundary haze, even though they have capacity to do so.”

He added that even though Thai authorities had imposed strict measures to control burning ahead of the next haze season, the actions were still limited to a national level.

“Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it is tougher for ASEAN nations to join forces and solve transboundary haze issues. But if there is no regional collaboration to develop legal instruments and frameworks to tackle the haze issue, we will continue to suffer smog every dry season,” Tara said.

The reporting for this feature series was made possible though funding provided by Earth Journalism Network.