Even as Vietnam faced its fourth wave of Covid-19 in January 2021, visitors to Dien Chau district could still find restaurants openly advertising all kinds of “exotic” meats, from rats and cats, to rabbits and monitor lizards.

What’s not openly advertised, yet even more famous, is Dien Chau’s dirty open secret – tiger products, including meat, bone wine, and glue.

“Hundreds of houses are farming tigers here,” said Mr L, a 45-year-old secondary school teacher who just happens to also be an illegal wildlife broker, while showing our undercover journalists around Dien Chau in January. “But they can’t export the tigers anywhere because of Covid-19.”

Vietnam has been a major destination and transit point for the global wildlife trafficking trade. Between 2003 and 2019, the country has been involved in the deaths of at least 15,779 elephants, 610 rhinoceroses, 228 tigers and 65,510 pangolins, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA).

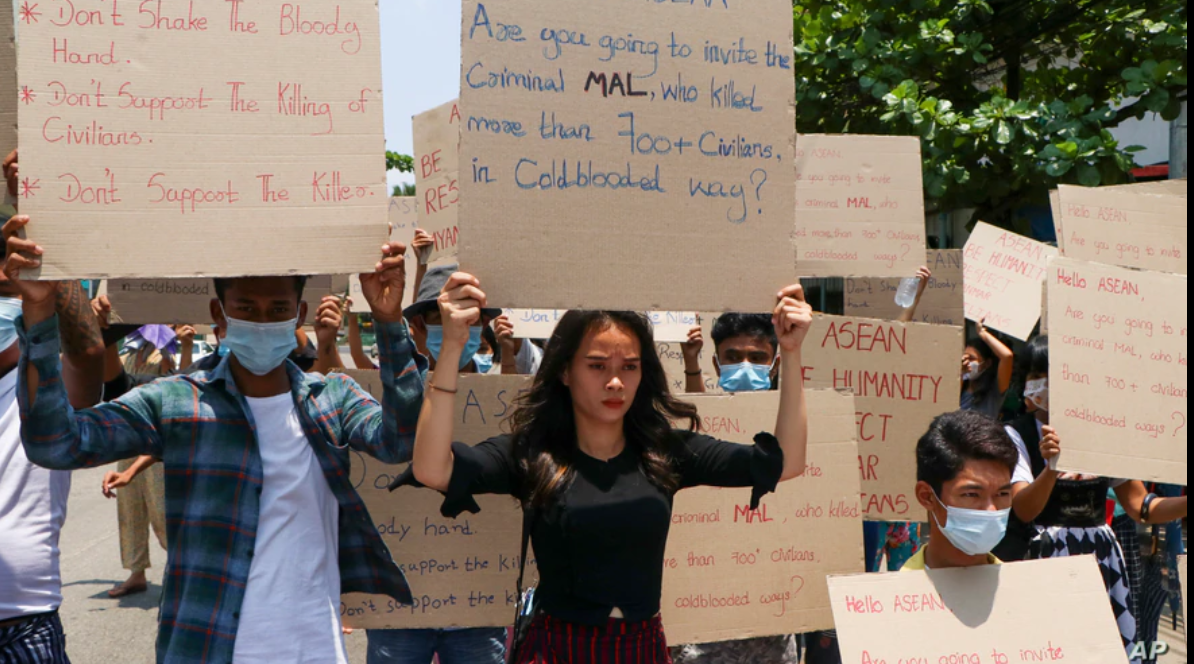

Given that scientists have widely considered Covid-19 a zoonotic disease (transmitted from animals to humans, or vice-versa), which may have emerged due to wildlife trafficking, both Vietnam and China – another major market for the illegal wildlife trade – have taken steps to tackle the issue. In February 2020, the Chinese government was compelled to ban the consumption of wild meat, and Vietnam followed suit in July 2020 with a Prime Minister’s directive to prohibit all wildlife imports.

Yet, questions remain whether two of the world’s biggest consumers of illegal wildlife can curb their appetite for exotic meats, even after such a global crisis.

As part of a collaborative investigation between the Environmental Reporting Collective (ERC) and the Vietnam-based Centre for Media and Development Initiatives (MDI), journalists went undercover as potential buyers to speak with four wildlife traders in early 2021, and analysed 10 years’ worth of data from nearly 300 wildlife seizure cases in Vietnam.

The journalists found a trade that is far from collapsing. Traders like Mr L and his associates are simply biding their time, pivoting to local and online markets while their goods remain grounded.

“Everything is still normal, nothing is curbed,” Mr L replied, confidently, when we asked if he could still supply tiger, rhino horns or ivory products within the country.

Education for Nature Vietnam (ENV), a local NGO which maintains a hotline for citizens to report wildlife crimes, recorded 2,907 wildlife violations in 2020, almost double the previous year. Without an aggressive crackdown on the trade while it is at its most vulnerable ever, experts fear traffickers would return stronger and more resilient.

We analysed and investigated the four most trafficked wildlife commodities in Vietnam – tigers, ivory, rhino horns and turtles – each of them a trade with its own complexities. Here’s what we found.

Tigers

Farmed tigers continue to fuel transnational networks

From the outside, it is impossible to tell a tiger farm apart from an ordinary house. “Only locals know,” said Mr L, rocking a black fedora with a suit and white T-shirt. According to government seizures and local media investigations, tiger farms have operated in Nghe An districts like Dien Chau, Yen Thanh and Quynh Luu from as early as 2012.

“The way it works is if you have money, you could ask someone to farm a pair (of tigers) for you. One puts in the money, the other puts in the effort. It’s like a profession,” the man explained.

“[They] can’t export the tigers anywhere because of Covid-19. Each house is holding on to hundreds of tigers, weighing 100, 200, even 300 kilograms,” he said.

While we could not verify the exact number of tigers currently kept in these backyard operations, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) estimated that at least 2,000 tigers are kept in such farms across Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam, with another 6,000 more in China. Since wild tigers are considered extinct in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, and the population is under 200 in Thailand, these tiger farms are the main sources of the trade.

Traders interviewed by the EIA claimed that Nghe An tigers are often sold to China, where the appetite for tiger bone wine and skin rugs is high. Investigations by DanViet and Nong Nghiep Viet Nam last year showed that prices for live tigers ranged from VND5.5mil-6mil (US$238) per kilogram, meaning an adult Indochinese tiger weighing 180-250kg [1] can bring in US$43,000 to US$60,000.

Mr L and several traders told us that farmers normally keep the tigers for eight to twelve months. After that, the tigers reach their maximum weight, and holding on to them will only mean losing profit over food and care.

“A lot of tiger traders, who previously were very confident about being able to get products via the border from Vietnam to China, have completely stopped offering that service because of border closures,” said Sarah Stoner, Director of Intelligence of the Netherlands-based Wildlife Justice Commission (WJC), during an interview with ERC in February. WJC investigators have maintained regular contact with wildlife traders in Vietnam throughout the pandemic.

Mr M, a tiger and monkey bone glue seller we spoke to in February, admitted that business has been bad. “It is difficult to travel around because of COVID,” said the middle-aged Phu Tho resident over the phone. “Otherwise, I can deliver anywhere you want, anything you want, fresh or frozen.”

Photo of tiger cub sent to our reporters by Mr M in February

“Because of COVID, so many departments are involved,” he explained. Vietnam’s land borders with China, Laos and Cambodia have been closed since March 2020. To prevent transmission through illegal border crossings, the military, police, border patrol and health workers were heavily mobilized throughout 2020 and 2021.

“The border routes the traders usually use are much more heavily guarded. There might have been a guard there who they were previously able to bribe and somehow find a way across, but now because of COVID-19 and extra enforcement, they can no longer get through,” said Stoner.

Yet despite stronger and more complex law enforcement, Mr M still seemed to be able to find his way around. In February 2021, he sent us pictures of tiger products via Zalo, a popular Vietnamese social media platform. The products included frozen bodies, whole skin, meat, bones, claws and even testicles. “[I] just cooked a 280kg tiger in Thanh Hoa, brought all the way from Laos. Just last December,” he told us.

“It wasn’t that strict then, compared to now,” he explained. “I tell you, it’s tight because of Covid, otherwise you don’t even have to be bothered.”

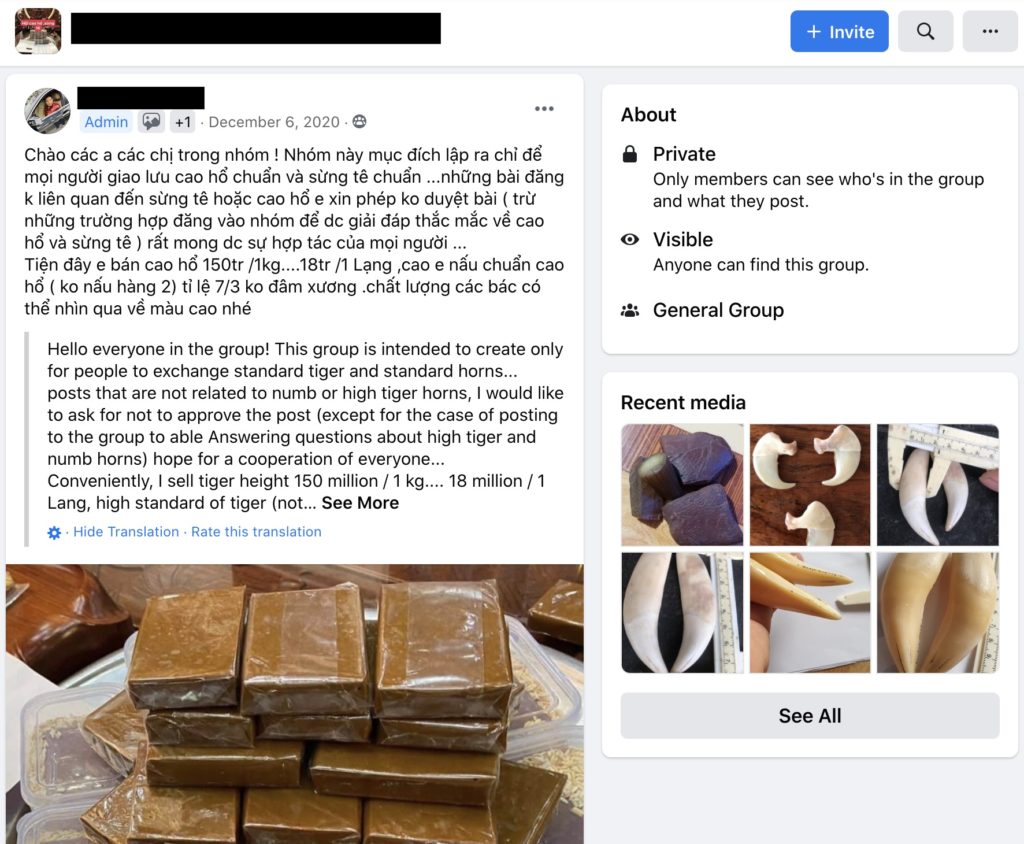

On social media, accounts advertising tigers are rampant. As recently as March 2021, we found ten accounts uploading daily images and videos of tigers in cages, slaughtered, and cooked into glue – and we found them all within an hour of searching. We also found a private group created on November 17, 2020 with over 900 members who regularly traded tiger products and rhino horns.

Based on Vietnam’s Investment Law 2020 and Decree 158 issued in 2013, advertising products made from wildlife listed in CITES Appendix I (tiger, rhino horns and ivory) is prohibited and can result in a financial penalty of up to US$4,354 (100 million VND).

According to Education for Nature Vietnam (ENV), a local NGO which maintains a hotline for citizens to report wildlife crimes, violations related to tigers hit 390 cases in 2020, up almost 70% from 2019. The majority of these violations were related to online advertising.

Last July, a Prime Minister’s directive assigned the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) to tackle illegal tiger farms in Binh Duong province and inspect commercial wildlife farming across the country. It did not mention Nghe An.

For conservation groups, the directive is long overdue. WWF has been campaigning against tiger farms since 2016, while the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) hopes the Vietnamese government goes one step further by calling for an immediate ban on issuing permits for commercial wildlife farms.

“Commercial wildlife farms are a high-risk interface for the transmission of zoonotic pathogens, as evidenced by viral surveillance in Vietnam over the last decade that has found multiple known and novel viruses in such farms,” argued the WCS, in an online article in response to the Prime Minister’s directive.

For Mr M, the only obstacle for his business now is the coronavirus. As vaccinations begin around the world and borders reopen, this will soon go away. But even now, Mr M is confident in his prospects.

“I’m only afraid of Covid. The world has banned the wildlife trade for years. I don’t care about any Prime Minister’s directive or police order.

“We make our own rules,” he said, using a phrase in Vietnamese (làm luật) that’s widely accepted as a reference to bribing.

Ivory

Past its prime, ivory finds new thriving territories

Before the pandemic, Mr L would never approach buyers unsolicited. To buy from him, you would have to show up and prove you were a genuine buyer. But this year, according to an undercover investigator with frequent contact with illegal wildlife traders, Mr L is actively reaching out to customers to clear his inventory – a few pairs of African ivory tusks.

In March, four other sellers in central Vietnam also broke their usual protocols to pitch a variety of products to our contact, from raw tusks to ivory rings and bracelets. These traders used to prefer meeting in person, but now a few text messages via Zalo can be enough to arrange delivery within the country.

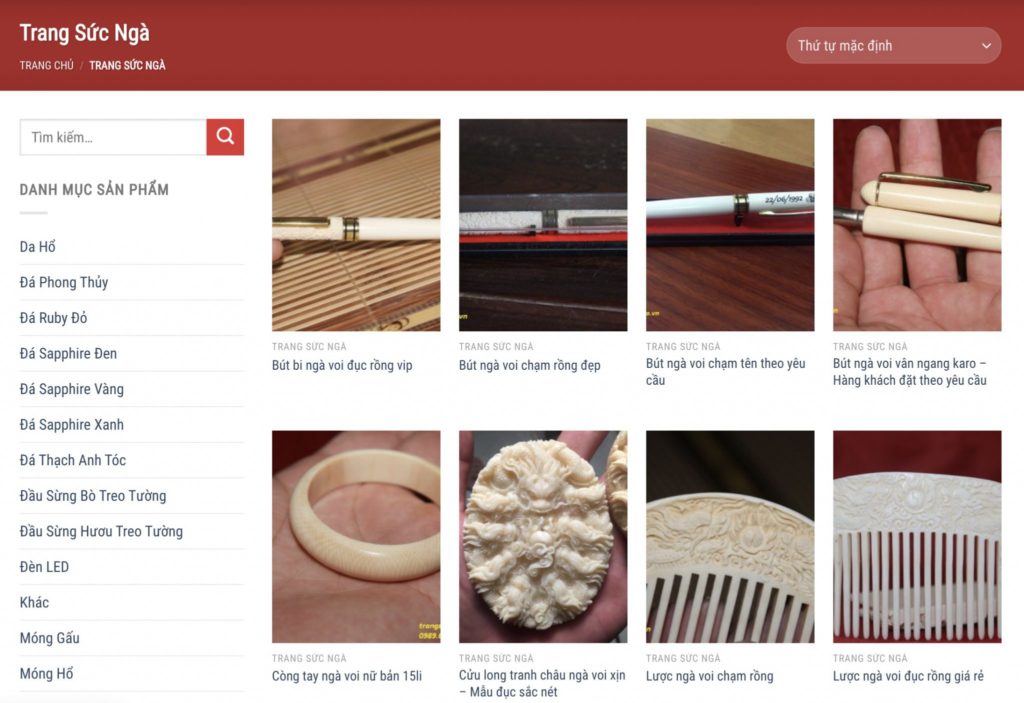

On Facebook, similar offers are common. After a few searches based on the word “ivory” (ngà voi in Vietnamese), we found countless ads for African raw tusks, ivory necklaces, bracelets, chopsticks or even milk tea straws, most of which guarantee nationwide delivery.

“Very cheap sale off, please message me,” wrote one account selling a plethora of ivory carvings on March 25, publicly. On an e-commerce website, ivory combs, pens and carvings are advertised online, together with other wildlife commodities such as tiger skins and claws.

As a key transit point and a consumer market second only to China, Vietnam has recorded the highest number of ivory seizures in the world. Experts believe there has been a shift in Vietnam’s wildlife trade activity since the pandemic. In 2020, ENV recorded 401 violations related to ivory, more than double the 184 cases in 2019. Most of the violations were related to online advertising.

“We have conducted market surveys where we’ve seen a lot of physical locations have shut, a lot of which appeared to have shut permanently. Meanwhile, there has been an exponential increase in online trade in all commodities in general,” said TRAFFIC Vietnam office director Sarah Ferguson.

Retail outlets selling ivory jewelry and trinkets to Chinese tourists were rampant across Vietnam before the pandemic. In 2017, TRAFFIC surveyed 13 popular ivory markets in the country, mostly tourist hotspots frequented by Chinese nationals such as Ha Long, Mong Cai and Nha Trang; and found over 6,000 ivory items publicly displayed at 852 outlets.

Yet last December, when investigators from WCS visited two of the same 13 locations, they found Nhi Khe and Mong Cai “quiet as ghost towns”. Since borders were closed last March, international visitors to Vietnam have dropped over 98%.

Efforts to export to China have also failed. None of the ivory traders we spoke to could guarantee delivery across the border like they used to. Investigators who work directly with traders at the wholesale level reported the same. “In the last 12 months, we have been offered much less ivory than we have in the past,” said Stoner.

The commission believes Covid-19 travel restrictions have exacerbated an ongoing problem before the pandemic – stockpiling. A report last April listed Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia as countries with large ivory stockpiles. In Cambodia, where Chinese nationals can now fly in, traders are waiting for spiked airfares to drop for the goods to move again. During a trip in January to Nghe An, we were able to witness one such stockpile, where traders like Mr L and Mr N get their inventory. Mr L admitted trade has been slow. “We don’t take much from the stock. We don’t want to hold the goods,” he said.

Stoner is unsure whether the products offered to her team are from stockpiles or newly arrived, but looking at seizure statistics, there has also been a clear disruption in ivory supply from Africa. Vietnam is the biggest destination of ivory in the world and our analysis of 95 seizures in the past decade showed that international shipments contribute to over 80% of the volume of ivory trafficked to the country, mainly from Africa. Since the pandemic, Vietnam has not seized a single ivory item arriving from Africa via this once bustling route. All seizures this year were of small quantities, at jewelry shops or during land transit.

“Shipping is the least affected sector by Covid-19, compared to airways and land transport. However, shipping has also endured many restrictions. For example, exports and imports are affected due to container scarcity, increased cost and delayed shipping. When smugglers use maritime routes, they often hide contraband in products exported via official channels. Because using official channels is already challenging, it could be one of the reasons why there were no maritime seizures in 2020,” said a Wildlife Conservation Society representative.

It appears the pandemic isn’t the only reason for the reduced trade in ivory. Consumption in China, the world’s largest ivory market, has been in decline since the country imposed a ban in 2017. When WWF surveyed 2,000 Chinese from 2017 to 2019, the number of people intending to buy ivory had dropped by half.

“A lot of the traders we engaged with have spoken of the ban in China and about how unattractive ivory has become. People just chose to trade other species because it was too dangerous,” said Stoner.

Since the ban, the value of ivory in supply and transit countries have both gradually dropped, according to a Wildlife Justice Commission assessment published in August 2020. In Africa, the average price of ivory has more than halved, from US$208/kg in 2017 to US$92/kg in 2020. In Vietnam, the price dropped to US$400/kg last June – the lowest ivory price ever recorded in the country, nearly half its value from just three years ago.

Nevertheless, the illegal ivory trade is nowhere near collapsing. During the first seven months of 2020, undercover operatives from WJC were still offered more than 27,500kg of ivory during investigations in nine African and Asian countries. In March 2020, WJC intelligence reported that some ivory containers had made it through one of Ho Chi Minh City’s ports.

In recent years, the Vietnamese government has handed heavy sentences to ivory traffickers. In 2019, three individuals in Hanoi were each sentenced to 10 to 12 years in prison for trafficking over 200kg of ivory. That same year, a South African named Melvin Van Zyl also got 12 years for carrying over 14kg of ivory in a flight from Singapore to Vietnam.

“Because of law enforcement actions that have been taken in Vietnam, it has been displaced to other countries in the region. We identified that this has happened in Laos and more recently in Cambodia. The Cambodian elements are very interesting because Cambodia never had an ivory market at all,” said Stoner.

Still, there remains much room for improvement in terms of law enforcement on maritime trafficking, which accounts for approximately 80% of the ivory trade. Based on our analysis of 27 maritime seizures reported in the media, only one resulted in prosecution – a 2012 case where two individuals were sentenced to a total of 56 months in prison for trafficking nearly 2.5 tonnes from Mozambique. In the other cases, perpetrators mostly avoided prosecution by using shell companies or simply denying that the cargo was meant for them.

“There is a need for governments to develop their intelligence capacity,” Stoner suggested. “We are talking about transnational organized crimes, similar to firearms trafficking, which use a lot of intelligence techniques. These are the sorts of techniques that should be applied to this [wildlife] problem.”

The pandemic might also offer a rare window of opportunity for the Vietnamese government to eradicate the ivory trade before normality resumes. “We know that there are stockpiles of the products in the country. This is a huge opportunity because it cannot move. This is an opportunity to investigate and to find out where those locations are, who they are linked to – those kinds of issues help you unravel organized crime networks,” said Stoner.

Rhino

A fast-moving commodity even for an idle year

Several years ago, the process for acquiring rhino horns was very different for Mr H, a wealthy rhino horn customer who knows every nook and cranny of the illegal trade in northern Vietnam. He used to walk straight into shops in Nhi Khe village and ask the owners to dump million-dollar bags of rhino horns on the floor for him to go through. Sellers would split the horns with an axe and weigh it in front of him to prove their authenticity.

This year, if he wants rhino horns, the sellers now only show him a small piece, just enough for him to tell whether it’s counterfeit or not. “Goods are rare now,” he said during a phone call in which we posed as an interested buyer in February.

A photo showing a piece of rhino horn sent to our reporters by Mr H in February 2021.

“They are cautious because many people ask, but few actually buy. Secondly, it is easy for them to get prosecuted for this crime. If that happens, they lose their stock, their money and their freedom,” he explained.

Nhi Khe, a village within one hour’s drive from Hanoi, was once dubbed “the world’s illegal wildlife supermarket”, after an undercover investigation by the Wildlife Justice Commission (WJC) revealed that the village was implicated in the trade of parts of up to 907 elephants, 579 rhinos and 225 tigers between 2015 and 2016.

When we visited the village in January, most businesses had already retreated behind closed doors due to the government’s crackdown on ivory and rhino horn businesses. But with Mr H’s help, we were still able to access a shop selling rhino horn powder in small quantities.

In February, raw rhino horns from Africa could fetch US$43,000 per kilogram in Vietnam, said Mr H. This is significantly higher than the price reported by WJC in 2017, which ranged between US$17,600 and US$22,300. In this range, the value of killing one rhino with two horns can reach over a hundred thousand dollars – much higher than poaching an elephant or tiger.

“Rhino horns are always moving,” said Stoner. Since the pandemic, her team has found no significant change in the volume offered to them by high-level traders in Vietnam, unlike the drop they have seen with ivory. “It’s very popular. It moves quickly.”

On Facebook, rhino horns are still offered daily on personal accounts and in secret groups. In March, we found at least two accounts trading rhino horns in bulk, each having at least a dozen horns in stock, based on the photos on these accounts. Rhino skin is also gaining popularity, often advertised in its raw form or as glue to cure impotence and digestive diseases.

While the influx of ivory from Africa seemingly stopped, rhino horns were still being trafficked from the continent into Vietnam in 2020 despite closed borders. Vietnam stopped all inbound flights aside from repatriation flights last March, yet the country still found three rhino horn deliveries via air cargo and passenger flights from Africa, according to state media Tuoi Tre and Phap Luat.

While the influx of ivory from Africa seemingly stopped, rhino horns were still being trafficked from the continent into Vietnam in 2020 despite closed borders. Vietnam stopped all inbound flights aside from repatriation flights last March, yet the country still found three rhino horn deliveries via air cargo and passenger flights from Africa, according to state media Tuoi Tre and Phap Luat.“It is known that corrupt officers at airports facilitate the clearance of smuggled products, but new Covid-19 measures mean traffickers are not guaranteed that the shipment will arrive at their port of choice,” said WJC in an assessment published in April 2020.

In one case in March 2020, a Vietnamese national smuggling 11 rhino horns from South Korea was caught after his flight was diverted to Can Tho airport, instead of Tan Son Nhat airport where he was due to land. He was sentenced to 12.5 years in prison last December.

Vietnam and China are currently the two main consumers of rhino horns. In China, horn powder is used in traditional medicine to treat fever, rheumatism, gout, hallucinations and even demon possession. In Vietnam it is believed to cure hangovers or even cancer.

Unlike the aggressive crackdown on ivory, China’s policy on rhino horns is somewhat perplexing. Although all international trade in rhino horn has been illegal since 1977, China only banned the use of rhino horns in traditional medicine in 1993. In 2018, the country decided to lift the ban, only to reverse the decision after it was met with a public outcry.

“I think the situation is quite the same, the threats persist,” Stoner remarked. “This is also a consequence of ivory being more closely targeted by the Chinese government as well – lots of individuals who previously trade in ivory have moved to different commodities. We know that a lot of them have moved to pangolin scales; maybe there has been a move to rhino horns as well because it continues to be in demand and it has held its value.”

Turtles

Exploitation of endangered turtles prevalent, with lack of regard for sustainability

“I can’t give you live ones, but dozens of kilograms of glue are no problem,” said Mr Q, a 50-year-old turtle trader based in the northern mountainous province of Bac Kan, when we inquired about wild turtles in February.

Mr Q admitted the turtle population has been in decline in recent years due to the rise of the turtle glue industry, but he assured us that locals were still out hunting to supply the trade.

“All jungle turtles. There aren’t any farmed turtles here,” he said.

Mr Q also guaranteed that nationwide delivery would be easy, even if we made the trip to collect the product ourselves. “Just tell them it’s horse glue. Nobody knows what’s what,” he said.

Just like tiger glue, the turtle version is advertised as a cure for arthritis and impotence, sometimes even to cure cancer. Because of this belief, Bac Kan province has become a major manufacturing hub for turtle glue, which is sold to both Vietnamese and Chinese markets.

According to ENV, the species being used to make glue are likely the keeled box turtle, an endangered terrestrial species endemic to Vietnam and several other countries in Southeast Asia. It is currently listed under CITES Appendix II, and according to Vietnam’s Revised Penal Code, violations related to this species can lead to a maximum 12-year imprisonment and a penalty of US$13,000.

The keeled box turtle is not the only one facing extinction due to exploitation. According to TRAFFIC and ENV, Vietnam has 5 native marine turtles and 25 native freshwater turtles and tortoises currently listed in CITES Appendices – meaning their populations are quickly declining and trade is either prohibited or restricted. Violations related to these species can lead to imprisonment of up to 15 years and a financial penalty of up to US$21,756, according to the Revised Penal Code.

Vietnam is identified as a part of the global illegal turtle trade, although not a major one, according to an investigation by the Wildlife Justice Commission in 2018. However, past seizures showed that the domestic trade is bustling. Turtles and tortoises are the second largest species group being trafficked in Vietnam after snakes, according to seizure data collected by Wildlife Conservation Society from 2013 to 2017. Many of these species, such as the Vietnamese pond turtle, leatherback and hawksbill turtle, are now rarely spotted in the wild.

In 2020, the number of seizures was up 14.3%, according to publicly available data. Endangered turtles were being transported nationwide using motorbikes or express buses, and also sold on the street, in restaurants, or even slaughtered and displayed publicly at wet markets.

In Ho Chi Minh City, for example, state media Thanh Nien reported yellow-headed temple turtles and elongated tortoises, both under CITES Appendix II, being sold by street vendors. The sellers claimed to have bought the animals from Cambodia and wanted up to US$430 each. Though several vendors have been caught and penalized, many were able to escape, according to ENV.

In Hanoi, batches of endangered turtles were sold publicly in front of Tran Quoc pagoda, a popular Buddhist temple. The turtles would be purchased for “mercy release”, a Buddhist tradition which promotes the freeing of unfortunate animals. The species included the Chinese pond turtle (listed as endangered in IUCN’s Red List) and red-eared slider, an invasive species. Without licenses, vendors could be fined up to over US$17,000 and imprisoned up to 15 years, according to ENV, which spotted the incident.

Chinese pond turtles ((Mauremys reevesii) and red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) sold in front of Tran Quoc Pagoda in Hanoi in February 2021. Photo via the Facebook page of Education for Nature Vietnam

Turtles and monkeys are the two species most often caught for “mercy release”, and are kept in captivity in temples throughout Vietnam. Last June, ENV sent recommendations to over 100 temples and pagodas across the country, pleading for them to follow regulations and replace the practice with more humane activities, according to state media.

On Facebook, many groups are publicly selling endangered species like the Indochinese box turtle, the elongated tortoise and the yellow-headed temple turtle. In March, we found numerous accounts publicly advertising these species, some of them from farms in southern Vietnam. To avoid prosecution, these accounts often use emoticons or slangs indicating sale, without using the words “sell” or “for sale” (bán in Vietnamese), an investigation in October 2020 by Lao Dong Online newspaper revealed.

For Mr Q, the turtle glue trade has been quieter due to the shrinking of the animal population and law enforcement. Many of his friends in the trade had lost their fortunes and after going to prison. Yet, at US$1,300 a kilogram, turtle glue is still profitable enough for him to continue the business.

Conclusion

While the Vietnam government’s response against the illegal wildlife trade in light of the Covid-19 pandemic has been applauded by conservationists as a stepping stone towards future legislative changes, it has not significantly affected traffickers’ mindset.

The traders we spoke to seemed unperturbed, and are simply waiting for travel restrictions to lift so they can resume business – and perhaps even up the ante.

“From a policy point of view, it is encouraging, but I don’t think it has made too much difference on the ground in terms of the criminals and brokers that we engage with,” said Stoner. “None of them that we spoke to have mentioned it. It’s not much of a deterrence.”

“I think once travel resumes, at some level we can expect to see a huge amount of trafficking,” Stoner added. “When people are desperate, they are willing to take risks that they probably would not take normally.”

“The government put out an instruction. (Now) they need to follow up with strong law enforcement efforts to make it clear that they are very dedicated to addressing this problem.”

Illustration: MDI/Thanh Ngoc Vy

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network. The story was also published by Environmental Reporting Collective and Oxpeckers