One summer evening, Truong Phi Hai lost his house to the Tien River, one of the two main branches of the Mekong River flowing through the delta in Vietnam. Three summers later, at almost exactly the same hour, the river claimed his house again.

The first time erosion bit into his soil, Hai, now 66, was watching Euro 2016 on his small TV screen. At around 3am, as Cristiano Ronaldo missed a critical penalty shot in Portugal’s match against Austria thousands of miles away, a strange bubbling sound roared from the backyard of Hai’s low brick home in the riverside town of Hong Ngu.

As the noise grew to a louder dull rumble, drowning out the screams of the match commentators, he left his TV and walked outside for a quick check. After a few steps, he heard a thunderous “Th-rump!”

Suddenly Hai saw his bed, tables, chairs, and finally the TV, with Ronaldo’s face on screen, slump down into a void that had appeared under his feet. The backyard where he was standing became a tiny islet surrounded by turgid water, and down it went.

“It was like I was riding a lift,” Hai recalled, gesturing downward with his hand. Shock froze his feet as his whole body was swallowed into the river. “I am dead!” he tried to cry. It was a quiet, clear-skied night in June. A few humming diesel-powered boats passed by in the distance, stirring the lazy water and the humid air.

While Hai was being pulled further from the broken bank, bobbing up and down amid the pieces of his house floating in the current, a crew member in a dredging boat docked nearby noticed his arm waving on the surface, rushed over and pulled him out of the swirling water.

“I counted myself lucky,” said Hai, sitting where his home used to be, pausing to draw on a cigarette. “So was my family, no one else was home that day.”

But in 2019, that luck ran out. That June, at around 3am, erosion struck again, chomping their newly-built tin-roof house and part of the front yard.

Feeling the rumbling, Mr. Hai, his wife, his son and an employee of his fish farm screamed and rushed out moments before the floor slid into the water. Snapped electric wires erupted around them like lightning. But his sleeping 85-year-old mother could not escape.

“It happened so quickly,” Hai recalled, with his vacant eyes gazing out over the lazy Tien River. People found his mother’s body the next morning. He buried her inside his third house, built with help from relatives, only a few dozen steps away from the newly-exposed river bank.

“There is little land left, it is like we are cornered,” he explained.

Mr. Hai’s experience is not unique in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. The Delta — more than 40,000 square kilometers of fertile soil, home to more than 20 million people, the rice bowl for a country of nearly 100 million and a major food source for all of Southeast Asia — is visibly vanishing under its residents’ feet, piece by piece.

Tens of thousands of families face the same threat that befell Hai and his family and need to be relocated. The danger looms larger by the year: there are now 564 riverine and coastal erosion hubs spanning 834 kilometers, a five-time increase from 99 hotspots a decade earlier.

Every day, the region loses on average one-and-a-half football fields of land to the rivers and the ocean, accumulating to between 300 and 500 hectares of land loss per year.

“The Mekong Delta is crumbling, with collapses happening at an unprecedented rate and scale,” said Nguyen Huu Thien, a delta-born conservation biologist.

Like any other river, erosion for eons has been part of the Mekong’s natural dynamic, he explained. Together with accretion, it sculpts the curves of the waterway. “But recently, the former is outpacing the latter in the delta,” Thien said.

In 2016, the same year erosion first took Mr. Hai’s home, local scientists started to warn about a much more worrying trend, the so-called “disintegration” of the Mekong Delta.

Land along river banks is failing to hold together because the river’s delivery of binding sediments is being curtailed. The delta’s existing resources, particularly its sand and freshwater, are being sucked out for human desires, accelerating the destruction.

With sea water crawling further inland every year, global climate change could bring a death blow to the resource-starved Mekong Delta. At this pace, it is now estimated that the world’s third largest delta may become uninhabitable within 80 years.

A young delta approaching a premature death

Many delta residents take the land for granted, as if it has always been, and will always be, right here. But the land they call home has only existed for a few thousand years.

For millennia, streams from the Mekong’s icy headwaters in the Tibetan-Qinghai Plateau have been meticulously grinding tiny grains off mountains as they waltzed through canyons in China and on into Myanmar and Thailand.

Extensive sediments too has come from the Three S River basin in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. And in fact, much of material making up the Mekong Delta has come from the eroding away of Vietnam’s own Central Highlands.

This sediment flowed freely carried by the swift currents through rapids and over waterfalls, picking up more material along its journey to the South China Sea. As the river traverses the lower, flatter plains approaching Vietnam’s coast, it slows and these sediments fall to the bottom.

The heavier material like sand and gravel settle first, while the finer alluvium travel beyond the river’s mouth. As the mud and clay flows into the South China Sea, some settles at the mouth of the river, and some is swept away by ocean currents, traveling southwestward and resulting in land expansion of 16 meters a year in the eastern estuary and 26 meters a year in today’s Ca Mau Cape.

Experts have estimated the Mekong River transported upwards of 165 million tons of solid material to the lower basin annually for the past 5,300 to 3,500 years. Over that time, the layers of silt piled up. The Mother River, as it’s called in the language of the earliest Khmer settlers, formed into the delta roughly 3,000 years ago.

Not all rivers exhibit these dynamics. Too weak a flow would fail to push the sediments over the same distances. Too fast a flow would not provide an opportunity for the silt to settle and accumulate. Stronger waves at the Mekong’s mouth could sweep away all the arriving sediment.

Indeed, the formation of the Mekong Delta is the result of a perfect balance of the region’s geology, hydrology and marine forces, the harmony of which human’s are now disrupting.

Blocking the flow

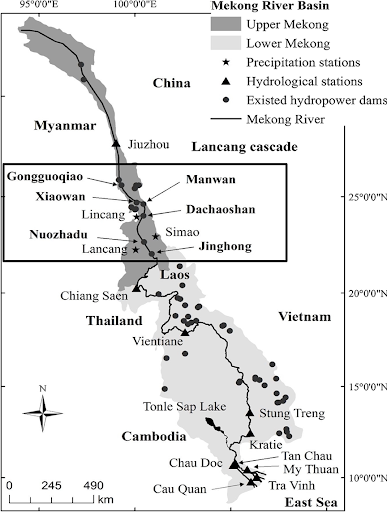

Back in 2010, when the Mekong River Commission estimated that the suspended sediment in the Mekong River to be 160‐165 million tonnes/year, it stated only about 42 million tonnes/year made its way to Vietnam. The commission found, that the construction of major hydroelectric projects, particularly a growing cascade of dams upstream in China, were blocking sediment flows.

Moreover, it warned that following the completion of dams then under construction this amount would be cut in half, and cut in half again should planned major dams along the river’s mainstem in Laos and Cambodia be constructed.

These water-fueled batteries affect the six nations of the Mekong in different ways. On one hand, they provide energy to the region’s booming economies. The lower basin countries can expect more than US$160 billion in economic gains by 2040 from full hydropower development.

But on the other hand, they hold up sediment and disrupt fish migration and spawning that contribute to the food supply for millions of people.

Vietnam, at the end of the stream, is the biggest loser. The delta’s fish stock has been declining due to the loss of nutrients that accompany the sediments. And since these sediments and nutrients also fuel the delta’s powerful agricultural sector, these fortunes too are eroding.

In 2020, a comparison of the pre-dam and post-dam data along the Mekong showed a 74 percent drop in the amount of sediment arriving at the delta from 1991 to 2015. Six mega-dams on the Mekong/Lancang cascade in China accounted for nearly half of the loss.

“It is certainly not because of any possible natural reduction in the sediment load,” said Doan Van Binh, a postdoctoral researcher at Kyoto University, who led the study.

“We found that in contrast with the downward trend reported at all stations in the lower Mekong River, there was a substantial increase of the annual sediment load recorded at the station upstream of the Lancang cascade,” he said in a virtual interview from his desk at the Disaster Prevention Research Institute in Japan. “It could only be the dams that have trapped the tiny grains.”

Nguyen Huu Thien offered a more vivid explanation, “reservoirs built in front of those upstream power plants slow down the flow.”

While lighter and smaller particles of the sediment can still float through the structure, the stream loses its energy there to push heavier materials, like sand or fish eggs, to continue their journey.

“With more dams being built, I cannot imagine a single grain of sand or gravel can slip through those reservoir walls to the Mekong Delta in the future,” he said.

Indeed, if all planned dams are constructed in the future, 94 to 96 percent of the sediment delivered to the seafronts could be trapped upriver. Projections by Vietnam’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development expect only 3-5 percent of the sediment load that was typical before the dams were built to be able to reach the delta by 2040.

That is a life threatening situation for the delta as a landform. Deprived of its natural building materials, the previously advancing delta is now sinking.

Recessions appear in the coastlines, soil collapses along the river banks, mangrove forests vanish as the ground holding their roots dissolves and sea water previously held back by the delta’s impermeable muddy shield at the river’s mouth now creeps inland through this thinning barrier.

Hungry water

To make matters worse, the dam-filtered water turns into what hydrologists call “hungry water.” As it becomes lighter, it runs faster, with greater energy.

“Whatever creature is hungry will always try to find something to eat,” explains Dr Le Anh Tuan, Vice Director of the Research Institute for Climate Change from his office at Can Tho University in Vietnam.

“The river with the excess energy that used to move sediment along now scours its banks and its riverbed to compensate for the reduced load.”

To restore the natural harmony, the river pierces deeper into the channel bottom while pulling down soil, and with it farmland and houses from the banks. In other words, the starving stream is nibbling off the very flesh of the delta it helped create.

For example, the first time Le Phi Ha’si house slid into the Tien River six years ago, research found that the base of the river was being severely incised, deepening at a rate of half a meter per year.

But as the Mekong River combs its own riverbed, seeking material to satisfy its hunger for sediment, there’s very little left here too.

Steel dredgers with their human operators are gouging out huge loads of sand and gravel all along the river bottom. This material is being transformed into urban infrastructure throughout the region. Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand and Cambodia all want the Mekong’s sand to build houses, offices, and shopping malls.

Wetland areas are filled to create road networks or expansive manufacturing and industrial zones.

“Before 2010 there was this assumption in Vietnam that riverbed sand is infinite, and its extraction would leave little impact,” said Tran Tan Van, director of the Vietnam Institute of Geosciences and Mineral Resources, a think tank of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

“Fleets of dredgers were unleashed in rivers in the Mekong Delta [to gather sand] to be sold to other countries, particularly Singapore; and no one actually kept track of how much had been sucked out of them.”

A survey by the World Wildlife Federation in 2011 – the peak of the Mekong’s extraction craze – found nearly 50 million tons of the material were being pulled out of the mainstream annually.

“In its natural state, before the 1990s, the river brought about roughly 20-25 million tons of sand and gravel into its channels and to its mouths,” said Marc Goichot, a researcher with the World Wildlife Fund’s Greater Mekong Programme and a co-author of the survey. “That is its budget.”

After the arrival of the dams, the number is estimated to have shrunk down to 3 to 5 million tons.

If you look at the Mekong as a bank account, he said, with the current debit totalled from the extraction rates in Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand, we are outspending the credit it provides by millions of tons a year. “You are eating your capital; your bank would not be very happy. That’s the situation today,” Goichot said.

With its channel geometry transformed, the Mekong has become what Vietnamese experts locally call “the river with an emptied belly”, scraping around for sediment to fill its pits and pools. Oftentimes it is the river’s banks that are literally pulled into the water to fill the voids being created below.

Collapsing coastline

The damage continues once the river reaches the sea. The precious remaining sediment now being trapped into those bottom trenches along the way means even less material arrives to the waterfront.

Without its tiny building blocks, the progradation of the Mekong Delta is slowing. Satellite imagery reveals that the Mekong Delta’s shoreline retreats more than 50 meters a year in some places.

The ocean waves, which helped shape the the delta’s landscape have also changed. For thousands of years, sediment pumped to the sea created a muddy thick coat along the shore, shielding the land against currents.

The disappearance of this coat turns the waves hungry, too. If one put two tanks of water in front of a fan, one containing tap water and the other murkier river water, one would witness different ripple patterns. The clearer water shows stronger waves on the surface, tapping the side of the tank, and the latter only gentle ripples.

“That is what has happened to the waves of the South China Sea,” Nguyen Huu Thien explains. “Sediment-deficient waves are now ripping the coast.”

Consequently, erosion now threatens more than 50 percent of the 600 km-long coast. Heaviest hit is the muddy South China Sea section, with 90 percent of it eroding.

Sixty percent of the Gulf of Thailand’s coast is also threatened by the sea. The pointy nose of Ca Mau Cape – mainland Vietnam’s southernmost tip – no longer exists. Erosion induced by sediment loss has rounded it off over the past decade.

Tran Van Loi has experienced this disappearance first hand. In the span of nearly 30 years living in a fishing hamlet on the Ca Mau Cape, he has moved his house five times.

“The first house I built was way out there,” he pointed into the ocean, a few hundred meters away from the coast. “You would not see the water from my house since the forest obscured the view,” the 55-year-old man recalled.

Things started to change around 15 or 16 years ago he says. The blue waves turned violent, lapping up against trees and houses in the hamlet. “Sometimes, the waves roar so loud, no one can sleep. We have to move women and children elsewhere for a few days,” he explains.

The soil began to break down, and his neighbors started to leave. Loi, a fisherman, decided to stay where his fishing boat docks. He now builds his new houses with tree trunks instead of concrete.

When asked about why he thinks his houses keep slipping into the water, Loi cited what he heard on the radio: “They said it is climate change, the sea rising and all. I think it must be true.”

Loi, however, is hopeful that a concrete embankment under construction nearby will put the erosion in check. It is part of the 90-km-long sea wall protection project for the eastern bank of the cape, which endures 20 to 25 meters of coastal erosion annually.

Thousands of kilometers of these concrete structures have been built across the Mekong Delta over the past decade. And some 3,300 billion VND (US$146 million) is earmarked for additional construction.

Sea walls and river embankments are considered a relatively quick fix for the growing erosion problems, but they are also an expensive one. For instance, Cau Mau’s in-progress sea wall reportedly costs between 20 and 45 billion VND (US$88,000 – 200,000) for one kilometer.

Estimates for the total funding required to combat erosion in the whole Mekong Delta region reach around 34,000 billion VND (US$1.5 billion), of which about 13,000 VND (US$570 million) should be allocated to building these barriers.

“The dykes don’t solve erosion, you move it to the next part of the bank, to somebody else’s,” Mark Goichot said in a Skype interview. His skepticism is shared by Anh Tuan, Huu Thien and Tan Van, who are also concerned about the environmental disruption and pollution concrete walls can cause to the already vulnerable brackish water ecology along the shore.

“Do not forget that the sea and the waves also have certain roles in sediment distribution for the delta and those walls might completely impede the shaping process,” said Tran Tan Van, the director from Vietnam Institute of Geosciences and Mineral Resources. “In other words, we are again going against nature and harming the land even more.”

Furthermore, adds Goichot, if one assumes coastal erosion is only the result of sea level rise, you risk ignoring the real reasons for the changes here. “And when you’re standing, say, on Ca Mau coast, looking at the sea, you think the problem is in front of you, while the problem is in fact behind you.”

Managing what’s left

Whether it is discussing disputes about how much Mekong water is flowing into Vietnam or what has happened to the sediment that is supposed to flow along with it, local experts join their international counterparts in calling for transparent data sharing and information exchange of water use and river monitoring among all the Mekong’s riparian states.

“The damage in the Mekong Delta is done and irreversible,” said the sediment tracker Doan Van Binh. “What Vietnam can be striving for now is not to recover, but to mitigate [the consequences]. To do so, we need data, we need information to build a reliable response and adaptation plan.”

Vietnam itself should also take a firmer stance on dam development on the Mekong mainstream.

Although it has repeatedly called on upstream states to respect the rights of downstream nations, two years ago Vietnam’s PetroVietnam Power Corporation was challenged for partnering in the development of the proposed Luang Prabang Dam in Laos. The 1,400-megawatt hydropower plant is expected to put people and land downriver at further risk, sparking fierce objections from environmentalists throughout Southeast Asia.

Vietnam should also do its part to address sand mining, but with a different and more thorough approach, the experts argued, because, while Vietnam and Cambodia have banned sand exports and the government has limited the dredging licenses it awards, the lucrative business continues to lure rampant illicit extraction.

Goichot and his team at WWF are engaged in a project that touches on the other end of the chain in Vietnam. It starts by getting people to understand the impacts of sand mining and the actual costs behind it in the Mekong Delta.

“If someone is building their house in Ho Chi Minh City, someone else in Ca Mau could lose theirs. That is not fair,” he said.

The team also aims to diversify material sources, promote responsible extraction practices and develop a tracing system that can help track sustainably harvested sand, like programs that already exist for timber and agricultural goods.

“The perfect solution would have been for us to stop the extraction ten years ago,” said Tan Van, a researcher who has studied the Mekong Delta’s geology and hydrology for 20 years. “But since it is impossible, we could start to find and adapt alternative sources for levelling and construction materials.”

Van points to the government’s Resolution 120 to save the delta, which tasks provincial authorities with tightening restrictions on the exploitation of sand.

“Everything is lined up in the right direction,” he suggests. “Now they just need to actually do it, and do it quickly.”

If the mining continues and dams keep blocking the vital sediment, he said, the future for Vietnam’s Mekong Delta is grim.

“It is like the fire has already reached our home, and there is little time left for us to extinguish it,” Tan Van said.

This leaves delta’s residents few choices but to make peace with their uncertainty.

Mr. Hai said he would keep living in his riverbank house, despite the two life-threatening incidents. “I don’t know when the next one will come; I guess we just have to accept the risk,” he said.

Downriver, Mr. Loi feels similarly. “When the sea climbs, we will have to climb higher,” he lamented.

Support for reporting this story was provided by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.