The rainy season comes and goes, leaving behind hundreds of thousands dengue fever patients. Each year, hundreds die of the disease. The recurring outbreak was bad enough before. Now mosquitoes have developed improved resistance to control measures, creating a new challenge for public health officials.

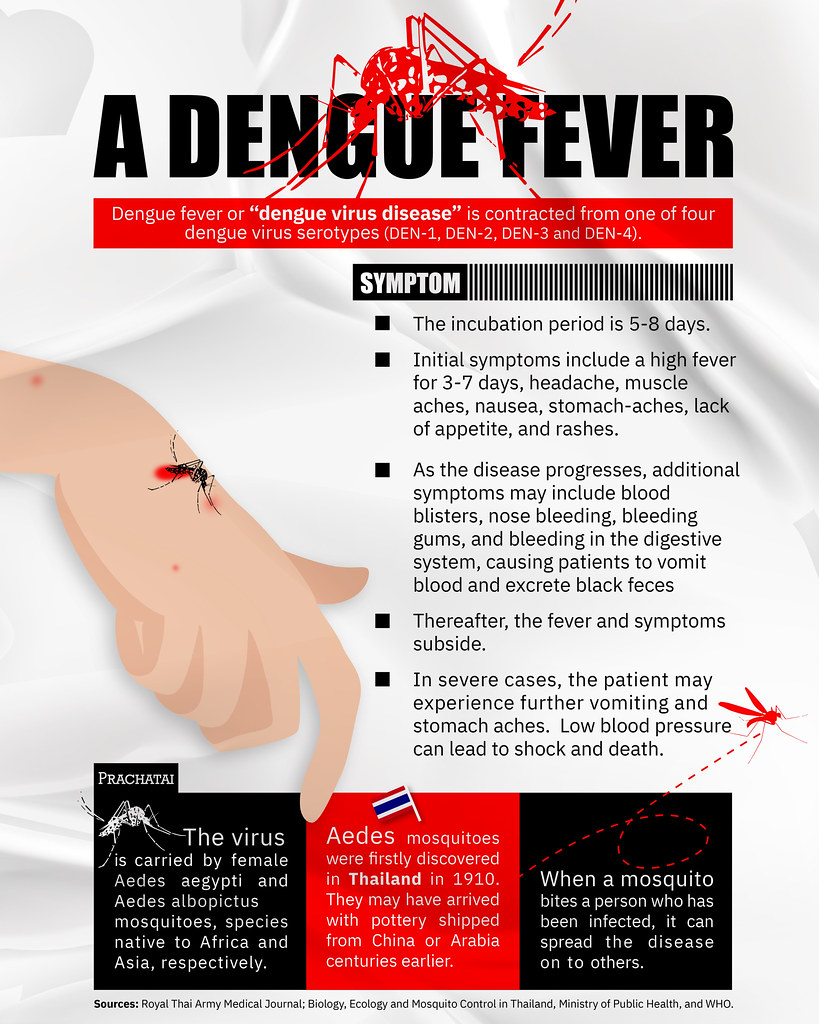

“My little brother and I thought it was just a head cold. But then we had strange symptoms. I lost my appetite and had diarrhea. My brother began vomiting. Our symptoms got worse. I often get a little dizzy, but with this, I was so dizzy I could barely get up. All I could do was sleep. We were like this for almost a week.”

Thananchanok Saengmanee, 17-year-old student from Bang Kachao subdistrict, Phrapradaeng district, Samut Prakan province, shared her experience of coming down with dengue fever a few years back. She had a fever and a sore throat. She also had ulcers in her mouth and diarrhea. Her little brother had similar but more severe symptoms. A blood test revealed that they had contracted dengue fever.

Thananchanok’s case ended well. Her brother recovered with treatment and she was able to look after herself after receiving medicine from a local health centre. But not all victims of this seasonal disease are so lucky.

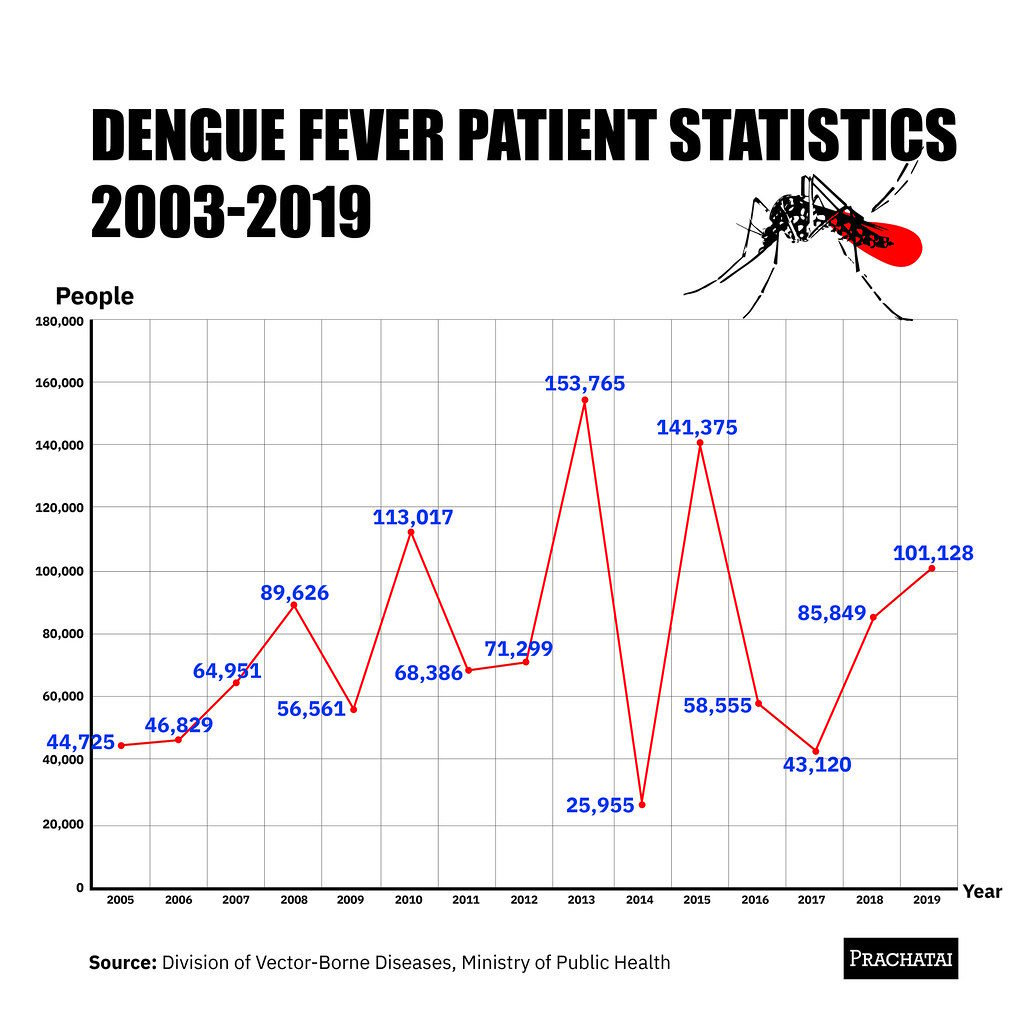

The Division of Vector-Borne Diseases in the Ministry of Public Health reports that there were 67,538 dengue fever cases with 49 deaths in 2020. The numbers were higher in 2019 – a total of 116,647 patients and 129 deaths. Between 2005-2019, the average number of cases was 77,000 people per year and there were 86 deaths per year.

At the global level, World Health Organization (WHO) data indicates that dengue is spreading across the world. In the decade after 1967, the disease was only reported in 9 countries. At present, it is in more than 100 countries, many located in the Asia-Pacific region.

In the past 20 years, the number of patients worldwide has also risen sharply, from 505,430 in 2000 to 5.2 million in 2020. Clearly, dengue fever and the Aedes mosquitoes that spread it are a becoming a serious public health issue around the globe.

New age mosquitoes: strong, tough

According to Dr. Darin Areechokchai, Deputy Director of the Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Ministry of Public Health, dengue fever is among the seasonal diseases with high mortality rates. Cross-border migration is a significant factor in local outbreaks. As outbreaks happen every year, continuous efforts are required to control Aedes mosquitoes.

Aedes mosquitoes share a history with people. Studies suggest that dengue-carriers like Ae. Aegypti migrated from Africa to the rest of the world along with humans. They later spread westward along Portuguese and Spanish slave-trading routes between West Africa and the Americas.

Along the way, Aedes mosquitoes adapted to changing environmental conditions. They switched from drinking animal blood to human blood. They also learned to lay eggs in man-made containers of still water and in closed spaces like ships, allowing them to reproduce and travel across the globe with humans.

At present, the movement of Aedes mosquitoes and dengue fever is still linked to human migration and trade. A report of the Pan American Health Organization notes that dengue fever moved with crowds of spectators attending the 2011 Pan American Games at Guadalajara, Mexico, as well as the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup and the 2016 World Cup in Brazil.

Aedes albopictus entered the Netherlands in 2005 along with imported lucky bamboo. Aedes aegypti rolled in with imported used tires. A 2008 study in Bangkok found that Aedes albopictus, Asian tiger mosquitoes, have increasingly taken up residence in human households, an adaption necessitated by the expansion of urban areas and diminished green space.

Climate change or “global warming” is another factor contributing to the spread of Aedes mosquitoes. Higher temperatures accelerate their growth and hasten the spread of the dengue virus serotype 2.

Mosquito-borne dengue spreads well in temperatures higher than 30 degrees Celsius. Mosquito larvae also need less time to incubate. At 30 degrees Celsius, they spend 12 days in incubation. At 32-35 degrees Celsius, they only need 7 days to hatch.

Control measures appear to be compromised. Previously, larvae were killed by putting abate sand granules in waterways. Repellent smoke was also sprayed to kill adults. Experiments conducted by Damrongpan Thongwat and Nophawan Bunchu in 11 villages scattered around 8 provinces in Northern Thailand found that larvae not killed by temefos, the active chemical used in abate sand granules, develop immunity to the repellents generally used in Thailand.

These contain pyrethroid, a synthetic chemical similar to pyrethrum or pyrethrins, which is found in plants from the chrysanthemum family. It is often used in agricultural and public health sector. Synthetic pyrethroids are modified to stick to surrounding surfaces for longer.

A study by Patcharawan Sirisopa et al. using samples collected from multiple sites around central and southern Thailand indicates that mosquitoes from all areas have developed a moderate to high level of resistance to synthetic chemicals in the pyrethroid family. This includes commonly-used substances like bifenthrin, cypermethrin and deltamethrin. The latter substance is found in spray can chemicals and high-altitude fogs. The mortality rate was reportedly less than 10%.

A further study of households at the Bang Krachao river bend, Phrapradaeng district, Samut Prakan province by Pathavee Waewwab et al. in 2016-2017 found that Aedes larvae were also developing immunity to temefos.

Commenting on the matter, Sungsit Sungvornyothin, a lecturer specialising in Medical Entomology at Mahidol University, pointed out that abate sand granule concentrations in the experiments were fairly low. He also added that fogs are usually composed of many different types of pyrethroids, increasing their efficacy. However, he acknowledged that routine and repeated fogging by local administration organisations may be accelerating mosquito immunity.

Dr. Darin believes that abate sand granules and pyrethroid sprays, if properly used, are still effective for mosquito control in Thailand. Temefos is photosensitive and if not stored properly, may lose its potency. Similarly, the improper mixing of chemicals for fogging, using the wrong type of fogger, or daily spraying conducted at the behest of politicians may also cause Aedes to have better survival rates and increased resistance to fogging.

Big city, big problem

Huai Khwang , a 15 sq km area with a registered population of 84,000 plus tens of thousands of unofficial residents, is one of the smaller districts in Thailand’s capital city of Bangkok. It has been at the top of the tier in terms of its dengue infection rate in many years.

On one occasion, hundreds of Chinese workers caught the virus while constructing the basement of a new building, sending Huai Khwang to the top of Bangkok’s dengue infection list. The district was also home to the deceased actor Tridsadee ‘Por’ Sahawong, who passed away from dengue fever in 2015, attracting massive media attention to health issues in the area.

Naphatson Rattanatayakon, a public health professional in the district, noted that dengue control measures were necessarily tailored to land use. One method was used with free-standing homes, another with apartments and office buildings and yet another with slum areas.

The well-off households have more areas to plant trees. Sometimes we can’t manage to spray there. They don’t want us to go in. When we campaign, they come out to talk, but offer excuses and don’t let us in. Some let us in. Some have breeding places with a lot of Aedes mosquitoes. It is an obstacle. It keeps us from covering the whole area.

“They only let us spray after they get sick. But when we first knock on their doors, they pretend they don’t hear us.”

Pradoemchai Bunchuailuea, a Pheu Thai Party member of parliament for Huai Khwang, and a former member of the Bangkok Municipal Council (BMC) and Huai Khwang District Council, has been involved in mosquito fogging and mosquito control efforts for 30 long years.

According to Pradoemchai, Bangkok administrative efforts still fall short of the mark because of residential areas that are not formally registered as communities, In housing estates and townhouses where there is little interaction between residents and government officials.

Registered community areas have a community council and Village Health Volunteers (VHV) who have been trained in dengue control. Pradoemchai says that statistics indicate that the number of dengue cases in these areas were lower than in the housing estates and townhouses.

“Lots of people living in housing estates suffer from dengue. There are more cases in the townhouses than in the slums. The slums have the health volunteers. The district works with them during the campaigns. They help distribute abate sand granules and make sure that anything containing stagnant water gets drained.

“This was before COVID. After COVID, district officers have not gone out into the field as much. The COVID situation made it tough for officers to go. They have had to adopt preventive measures,” Pradoemchai said.

The fogging method advised by the Ministry of Public Health is limited to a 50 sq m area around a house. In contrast, Pradoemchai’s fogging team tries to cover as wide an area as possible. With 3 fogging machine and 6 sprayers, his team is even larger than the district’s, which has only 2 machines and 2 sprayers.

Sprayers know that they are not solving the problem, however. The mosquitoes invariably prevail. And fogging can sometimes be difficult in densely-populated areas where residents hold different opinions.

“The number of mosquitoes never decreases. Every year when the rainy season ends and winter begins … the ground is waterlogged. Mosquitoes lay their eggs and the virus spreads. Are less people getting sick? Not really. And the number of mosquitoes doesn’t decrease either. There are always more of them.”

“The sprayers try to provide people with basic information and ask for their help in draining containers with water where mosquitoes lay eggs and spread the disease. Otherwise more will hatch than can be killed by fogging. But some people think that fogging helps, that it will keep them safe, and they feel more secure,” Pradoemchai said.

“[Before going to spray at a site where someone has been infected] I have to call and check with the person who is ill. It may not be convenient. I have to ask about their surroundings. If there is a store, it has to close. There can be problems. For cases in the field or in office environments, the chances of getting bitten by a mosquito are low. But things need to be thought through. We can’t just spray and caused negative side effects. I was once grabbed by the collar and almost punched by a guy who had a pet chicken valued at tens of thousands of dollars.”

“The Ministry [of Public Health] would rather we didn’t spray. They told us that it is better to take care of the breeding spots and mosquito larvae. Once they mature, they are harder to kill and die more slowly. Young adults fly away. If we spray and it hits them directly, it’s possible to kill them but they don’t all just drop dead. The older ones might. People think fogging helps. I think we spray to make them feel better,” Naphatson said.

Money matters can sometime be a boon for mosquitoes. For example, a 2020 policy to collect taxes on unused land in Bangkok caused ‘farms’ pop up on previously vacant lands. Having more green spaces may sound like a good thing but is also created new mosquito breeding areas.

“Sometimes they left big spaces for water storage or created raised-bed orchards to plant trees. There was a loophole in the law. Instead of paying an expensive tax on an abandoned space, people could plant trees and register their property as agriculture land with a lower tax rate.

“People living in nearby condos were affected and asked us to fog because there were lots of mosquitoes. But we couldn’t get in because the property was fenced off. It is still an issue. It’s a problem when empty lots have water sources, stagnant or clean. It is a breeding ground for mosquitoes, especially Aedes mosquitoes. We can’t do anything and don’t know how to address the problem,” Pradoemchai said.

“Huai Khwang also has them, swampy places covered in sedge grass. Where there’s water, there are Aedes mosquitoes. In the past they had us attend to these places as well, but it was just too much. There are whole fields out there; how could anyone put down enough (pesticide) to cover them? The immediate problem is here with the empty spaces in Bangkok. The owners don’t fill the land. It gets covered weeds and becomes a water source,” Naphatson said.

Resources lost to COVID-19

According to Dr. Darin, mosquito control operations were transferred from the Ministry of Public Health to local administrators over a decade back. Ministry officials now act as consultants. The plan was to increase local cooperation in control efforts.

In recent years, the spread of the COVID-19 has also drawn public health officers’ attention away from dengue. The listed number of cases in 2021 of about 8,000 may not be accurate as officers have not had enough time to collect data.

At the Bang Kachao river bend where Thananchanok got sick, the number of dengue cases has slowly decreased, from 5 in 2018, to 3 in 2019 and only 1 in 2020, defying a terrain full of swamps, overgrown gardens and households built over canals.

Thananchanok believes that the number of mosquitoes has greatly declined. In the past, mosquitoes would land on her arms and legs as soon as she went out to cook in the kitchen.

This may be due to prevention measures. Chamaiphon Saengdaengchat, director of the Bang Kachao Tambon Health Promoting Hospital (THPH) explained that the hospital has been training health volunteers, community leaders and people in the area to control mosquito breeding areas.

“We focus on training programs for village leaders. We invite them to the training and after it is over, we go around the villages with them to talk to villagers. We have done it 2 times. We only asked for that much budget. In addition to two training sessions, we also campaign together with village volunteers and municipal officers 4 times a year.”

“After the campaigns, we have health volunteers check for mosquito larvae. A team evaluates what they find and takes steps to eradicate larvae … it supports the project.”

With the spread of COVID-19, the hospital had to reallocate resources, reducing the budgets for other projects. Health volunteer control efforts were continued but measures had to be taken to protect the people involved. As at Huai Khwang, the need for social distancing over the past couple of years ended house-to-house campaigning.

The situation is similar in Ban Krachao subdistrict, Samut Sakhon province. According to Patawee Puakphromma, a public health official at the Bang Krachao THPH, there have yet to be any cases reported in 2021. Normally, twenty people get the virus each year. The number was higher in 2015-2016, with 30 cases. With the spread of COVID-19, resources have been diverted from earlier projects but mosquito larvae extermination activities and household checks continue as normal.

According to Dr. Kittipoom Chuthasamit, director of the Phusing Hospital in Srisaket province, the number of dengue cases there has fallen as a result of drought. Normally the area has 25-30 patients a year but after a two-year drought, only 8 cases were reported this year. This is fortunate as there, too, the spread of COVID-19 diverted resources away from mosquito control.

“We were very active before COVID-19. Dengue is one of the first diseases we need to prevent because it breaks out almost every year. But when COVID-19 came, we had to start disease control, give swab tests and vaccinations. We allocated resources to COVID-19 and may have neglected dengue. Actually, it’s not neglected. We had reprioritise. It was no longer the most important task. It was second or third.”

More cooperation is needed

According to Kittipoom, dengue control in Thailand consists of 3 parts: 1) getting rid of mosquito larvae breeding areas by eliminating stagnant water and pouring abate sand granules into stored water, 2) getting rid of adult mosquitoes with fogging and 3) providing patients with rapid treatment to prevent further disease transmission by mosquitoes. Officials at every hospital agree.

The challenge is often about getting people with limited resources to cooperate and address the needs of big populations in complex urban settings. It has to be done. Not dealing with larvae breeding spaces in one area places surrounding areas at risk. The shadow of dengue remains, everywhere.

“In densely populated, congested areas, people have different hygienic practices. In congested communities, garbage increases. At dumps sites, larvae can actually be found in the garbage; after it rains Aedes larvae hatch in water-soaked containers,” Patawee said.

“We humans need to be aware. We need to know which parts of our house can become breeding grounds for Aedes mosquitoes. At the same time, mosquito control officers need to understand how people behave. A plastic container, a water barrel – these things are used differently in different homes. Containers serve different purposes. When we tell people to turn them all upside down, it is simple idea that doesn’t really reach people. Other mechanisms need to be involved,” Sungsit said.

Naphatson agrees that if people pay more attention to getting rid of Aedes mosquito larvae in their own areas, it will cut the breeding cycle of disease carriers and greatly decrease the risk of dengue.

“People lack awareness and concern. They are not interested and don’t cooperate, unless we spoil them. Sometimes, when we provide them with knowledge, they don’t understand.”

“People don’t do enough to avoid getting bitten by mosquitoes. If we all cooperate and help each other, we can do it, but if people request fogging and don’t do anything else, it is not enough. Destroying breeding spots is the best preventive measure,” Naphatson said.

With ongoing calls for cooperation and repeated efforts to control this vector-borne disease, dengue continues to spread in Thailand. How can dengue disease control be made truly successful?

Read the answer in part two of this special report soon.

Support for reporting this story was provided by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network. It was first published on Prachatai.