Data on agricultural, hydropower, saltwater intrusion and rainfall patterns in Vietnam Mekong Delta explains where the country’s food comes from, why it’s disappearing and what can be done about it.

The fertile Mekong Delta is a crucial region for Vietnam’s continued food and economic security but a variety of factors have wreaked havoc on how Vietnam grows food, catches fish and ultimately survives a radically changing environment. Here, reporters analyze 20 years of data on agricultural, hydropower, saltwater intrusion and rainfall patterns in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta (VMD) to explain where the country’s food comes from, why it’s disappearing and what can be done about it.

1. Disappearing waters

Vietnam’s flood plains are disappearing, and fish, rice and people along with it. The flood peak in Tan Chau and Chau Doc in 2020 is only about 60% of that in 2002. From now on, VMD will have to wait from 50 to 100 years to have a big flood season. Within 15 years, the amount of fish caught in An Giang has plummeted by two-thirds.

The area of rice cultivation in Ca Mau has decreased by 30,000 ha, equivalent to the entire capital city of Ca Mau or 42,000 football fields. In 2019-2020, saltwater not only penetrated 10 km deeper than before, but also arrived earlier and receded more slowly than the annual average.

Since 2006, more people have left VMD than have migrated from other regions as growing food becomes riskier and more expensive.

2. VMD’s annual floods are a distant memory

The flood season in VMD starts in June and ends in November every year, or at least, it used to. But with 2021 witnessing another low flood season, the region has not seen a major flood in more than 10 consecutive years.

The Mekong River flows into Vietnam through the Tien and Hau rivers. According to data from measuring stations in Tan Chau (upstream of Tien River) and Chau Doc (upstream of Hau River), the highest water levels in these rivers have overall been falling for nearly two decades.

Compared with the average highest water levels between 2002-2019, the highest water level in 2019 was lower by about 25% in Tan Chau and about 20% in Chau Doc.

3. Hydropower dams cause most of the water loss

The Mekong River flows through five countries—China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia—before entering Vietnam. All of these countries see hydroelectric power as crucial to their growth.

“Flood water in the Mekong Delta depends a lot on the water and energy demand of upstream countries. Mekong River. As the demand for irrigation water and energy increases in the upstream, it is clear that the water coming to VMD will decrease,” said Associate Professor, Dr Nguyen Nghia Hung, Deputy Director of the Southern Institute of Irrigation Science of Vietnam.

Up to 95% of the total water flow in VMD comes from upstream Mekong but that water is now stored in hundreds of lakes and hydroelectric dams upstream.

4. To generate electricity, dams interfere with natural flooding patterns and growing seasons

According to Associate Professor Dr Nguyen Nghia Hung, the dams store and then discharge water, using the difference in pressure to generate energy.

Hydroelectric dams usually store water during the rainy season, and discharge it when the demand for electricity is high, usually during the dry season. Therefore, river water could not go up and down naturally as in the past but according to the demand for electricity, or the dam operation.

They also change the flow of water downstream to VMD, leading the water levels in Tien and Hau rivers to gradually decrease in height. This is expected to worsen, when upstream countries build more hydroelectricity plants and increase hydroelectricity capacity.

According to calculations by the Southern Institute of Irrigation Science, from now on, it will take 50 to 100 years for VMD to have as high floods as before. High floods mean the max water level rises above the alert type III, which is 4.5m in Tan Chau, and 4m in Chau Doc.

5. More planned dams mean more problems

By 2021, the upper Mekong River has 141 hydroelectric plants in operation. In addition, there are 36 more under construction. By 2032, there will be a total of 468 hydroelectric plants on the Mekong River and its tributaries.

Hydroelectric capacity has also increased continuously. By 2032, all hydroelectric plants on the Mekong River will have doubled their capacity compared to today. While most of these plants are not located in Vietnam, they are adversely affecting the living conditions of more than 17 million people in VMD.

Landslides are also a constant threat in VMD and may be made worse by dams. A study on environmental change and migration in VMD, led by Dr Nguyen Minh Quang, a lecturer at Can Tho University, showed that in 2016, severe landslides eroded a total of 980 km of coastal and riverside areas, causing 121 families to lose their houses.

This study also estimates that, by 2016, water washed away 800 hectares of coastal land and mangroves annually in VMD.

6. Climate change is making weather more extreme, bringing wetter rainy seasons and drier dry seasons

5% of water in VMD comes from rainfall. Total rainfall in Vietnam has not changed significantly since 1960, but in some areas in VMD, rainfall increased during the rainy season and decreased during the dry season. This makes resilience to changing flood patterns even less likely.

For example, in Kien Giang province, in 2020, rainfall increased by nearly 30% in the monsoon season but decreased by nearly 30% in the dry season compared to the average in the period 2017-2019.

Similarly, in Ca Mau province, in 2020, rainfall increased by about 10% in the monsoon season and decreased by about 25% in the dry season compared to the average between 2000-2019.

The dramatic reduction of rainwater in the dry season has made farming more difficult in the dry season.

7. Fishermen were among the first to raise the alarm over flooding

Phan Chi Hieu, commonly known as Muoi Diep, has been raising fish in cages for many years at Ong Ho Island, My Hoa Hung Commune, Long Xuyen City, An Giang Province. Previously, Muoi Diep’s family had 20 fish cages, each year harvesting 400 tons, mainly for export because of the area’s proximity to Cambodia. By October 2021, he only had 6 fish cages left and caught 70% less fish.

It is also taking longer for the fish to mature, from four months in the past to six months currently, raising the cost of growing them, he said.

The costs of fish food and medicine have also increased. He often has to move fish cages and harvest immature fish when they are not big enough, to make way for the dredging and river improvement activities. Mr. Muoi Diep said the activities are mostly for sand mining.

8. Fish are disappearing fastest in the Mekong Delta

An Giang province, Muoi Diep’s homeland, has also seen the largest decrease in the quantity of fish caught in VMD compared to 15 years ago. In 2019, fish catch in An Giang was only 28%—less than a third—of its catch in 2004.

An Giang is not the only province experiencing a decrease in fish catch. Out of the five landlocked provinces and city in VMD, only Dong Thap has seen an increase in fish catch since 2004. The remaining four, Can Tho, Vinh Long, Hau Giang and An Giang, all caught less freshwater fish than before.

9. Vietnam’s rice bowl is shrinking

The Mekong Delta is still the rice bowl of the country, contributing over half of the nation’s total output. In 2020, 13 provinces in VMD produced 55.7% of the country’s rice. However, like inland fishery caught, rice production in the Delta has been on the decline since 2016.

10. Rice decline is driven by the absence of flood waters

In general, the area of land growing rice in VMD is on a downward trend, especially for the winter paddy. Also known as floating rice, this crop is VMD’s specialty.

Floating rice plants take nutrients from alluvium in flood water to grow, often requiring little fertilizer. While they are nature’s gift for VMD, their cultivation tends to gradually reduce the cultivated area if there are fewer floods.

11. A shift away from rice reflects a new reality

The area and production of rice decreased gradually from 2016, coinciding with the implementation of Resolution 120 on sustainable development in the Mekong Delta in response to climate change.

According to this resolution issued in 2017, inefficient rice growing areas are converted to growing drought- and salinity-tolerant fruits and vegetables.

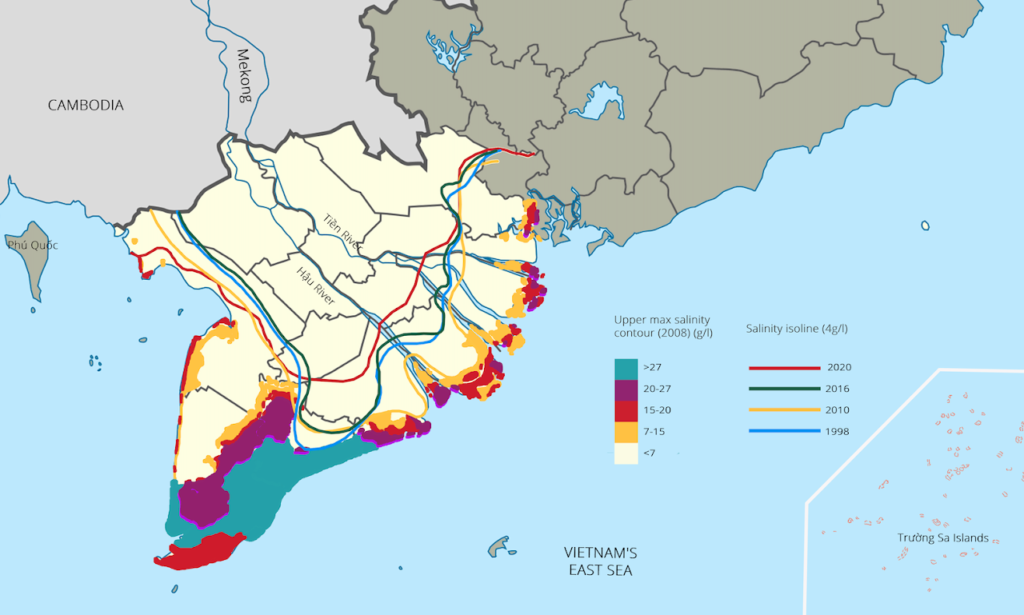

12. When fresh water disappears, salt water rushes in

Saltwater intrusion due to sea level rise also shrinks land suitable for rice paddies. According to a study on salinity in VMD by Edward Park and associates, published in June 2021 on Ambio, a journal of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, during the 2019-2020 dry season, seawater penetrated 110 km inland, 10km deeper than the historical average.

Not only that, it was detected about 2.5 to 3.5 months earlier, and withdrew a month later than average.

13. Seawater intrusion causes widespread water shortages

During the 2019-2020 dry season, saline intrusion caused shortage of fresh water to more than 40,000 households living along the coast in VMD.

14. Salt poisons water for farming rice, vegetables and fruit

High salinity intrusion caused salt contamination, rendering unsuitable for farming 30,000 ha of land for rice in Ca Mau, and 20,000 ha of land for fruit and 6,500 ha for vegetables in Ben Tre.

Rice can grow in land with 3-4 grams per litre (g/l) of salinity. However, some areas recorded salinity above 7g/l (orange areas on the map), 15-20g/l (red), 20-27g/l (purple), or up above 27g/l (blue), nearly 9 times higher than the threshold of common rice.

15. Many people in VMD had already shifted away from life on the water, then came back to it when the pandemic struck

In October 2021, Danh Thi My Thanh, 26, returned to her 36-year-old husband’s home town of Ngai Tu commune, Tam Binh district, Vinh Long province with their three sons aged eight, four and two after factories in Binh Duong province, where they have been working for seven years, closed due to COVID-19.

In Vinh Long, women like Mrs. Thanh often go to pick fruit for garden owners. Thanh’s husband often works in construction projects. Income is about 200,000-250,000 VND (8-10 USD) per person per day.

During the days when she does not have a job, Mrs. Thanh stays at home to help her husband’s mother make rugs from dried water hyacinth yarn. She makes at most four rugs per day, which are sold for 70,000 VND (2.8 USD) each.

She is waiting for the COVID-19 pandemic to pass and the factory to reopen so she can return to work in Binh Duong. Mrs. Thanh said her family migrated because jobs were scarce and lower-paid in her hometown.

16. Generations of people in VMD pushed out of the countryside and into urban areas or even out of the country entirely.

In general, the number of people leaving VMD is more than the number of people moving there. The net migration rate (immigration minus out-migration ratio) of VMD has been negative since 2005.

During 2010-2020, the Mekong Delta’s population remained at over 17 million people but with a slow but steady decline as new babies being born fail to compensate for deaths and people leaving.

In 2020, for every 100 people, one person was lost, likely to migration. The provinces with the largest population decline in 2020 were Hau Giang with the highest loss, followed by Tra Vinh, Soc Trang , An Giang and Ca Mau.

According to a 2011 study, seven out of 10 people leaving VMD went to the Southeast region, mainly to Ho Chi Minh City and Binh Duong, where many industrial zones are located.

17. People from the delta are poorer than in the rest of the country

In 2020, the average Vietnamese person earned 10% more than people living in VMD. Workers in Binh Duong, Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi earn 82%, 69% and 60% more, respectively, than those in VMD.

Even within VMD, income disparities exist between provinces and sectors. In 2020, residents of Can Tho had the highest income, with an average of 5,031,090 VND/month, while those in Ca Mau had the lowest, 3,034,400 VND/month.

In 2020, in VMD, agriculture, forestry and fishery sectors contribute only one-fifth to the monthly per capita income.

18. People from the Delta struggle for jobs

Unemployment and underemployment rates are very high. From 2010 to 2020, VMD has had both the highest unemployment and underemployment rates in Vietnam.

Underemployment is when a worker has a seasonal, irregular job, or a job that requires less than the worker’s capacity and qualification.

19. The government plan pivots to making do with bad water

In 2017, the Government issued Resolution 120 on sustainable development in the Mekong Delta adapting to climate change and in 2020, Decision 324 approving the master program for sustainable agricultural development in the Mekong Delta, to orient solutions for the development of VMD.

These legal documents specify using water resources, including freshwater, brackish water and salt water, as the core of the region’s development. This encourages VMD to shift its strategic axis to seafood, fruit and rice, according to market needs and not just focus on rice and fish as in the past.

“We still think that VMD is the lower Mekong River, but we forget that this is also an area open to the sea with opportunities brought by the sea,” said Dr Duong Van Ni, lecturer at Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources, Can Tho University

Many areas where rice growing was inefficient have been converted to grow more salt- and drought-tolerant crops, such as dragon fruit, coconut, lotus, areca, and watermelon.

20. VMD will still rely on agriculture, but what to grow is an open question with many experiments underway

Dr Duong Van Ni said: “The change in attitudes about food security is the key to unlocking the potential of VMD. For 40 years, we considered VMD as a granary to ensure food security for the country.

Today, the concept of food security has expanded, food is not only rice, but also many other products. Economic security is also focused. Top-down directives, like Resolution 120, really gave people the key to open the door to a new space.

But what to do in the new space is entirely up to the people to decide. They are proactive in transforming crops, livestock, and livelihoods.”

Local authorities in VMD are working on crop conversion. Tran Anh Thu, Vice Chairman of An Giang Provincial People’s Committee, said the province is implementing a number of key experiments for sustainable development.

21. Freshwater storage becomes increasingly urgent for adaptation

Local authorities are using small- and medium-scale freshwater storage systems to adapt to changes in climate and dry season freshwater depletion due to hydroelectric dams blocking water flow.

22. Citizens are urged to shift from wild fishing to fish farming

An Giang Department of Agriculture and Rural Development is encouraging people to move away from wild fishing to aquaculture, such as growing snakehead fish, perch and shrimp.

An Giang is participating in the “One commune, one product” program launched by the government to connect farmers with markets and create jobs for rural people.

23. Industrial parks and economic zones employ former agricultural labor

An Giang is also attracting investment in industrial parks and economic zones, giving priority to enterprises such as shoes, garments, seafood processing that use local laborers, so they do not migrate to Ho Chi Minh City or Binh Duong.

Tran Anh Thu said that there is a need for government regulation to build more transport infrastructure, seaports, and preferential policies for investors in VMD.

24. Education and cooperation are key to achieving resilience

According to the report of the People’s Committee of An Giang province on the implementation of Resolution 120, in January 2021, the province is also focusing on education, training, communication and international cooperation.

These include drawing up agreements on to climate change response, water resource management, and infrastructure development with international partners.

There are non-infrastructure solutions too to help people adapt to the changing conditions. These include constant communication with the community about water sources, drought and salinity, pollution, and landslides, among others.

There is also a need for knowledge sharing among the network of universities and research institutes, agricultural and fishery extension offices and relevant domestic and international agencies.

25. The dams must go

Discussing the overall solution to water resource management for sustainable development in VMD, Associate Professor Dr Nguyen Nghia Hung, Deputy Director of the Southern Institute of Irrigation Science, said damaging projects should not be undertaken in the first place.

He also said increased use and popularity of other renewable energies such as solar and wind could mean demand for hydroelectric dams is likely to decrease in the future.

In the meantime, however, managers need to repair, change operating procedures of existing works, and create new regulations and strictly control the environmental impact assessments to ensure projects are environmentally-friendly, create a beneficial ecosystem, and are planned properly, with a high degree of integration and support for the community.

Methodology

The authors used the General Statistics Office of Vietnam (GSO) database to obtain data on rice production and area, fish catch and production, water levels, income, employment, and migration. GSO is an agency under the Government of Vietnam, with the function of advising the Ministry of Planning and Investment of Vietnam in the state management of statistics. Data on the number and capacity of hydroelectricity plants on the Mekong River are available on the website of the Stimson Center, an international peace and security think tank based in Washington D.C. Rainfall data are collected at Vietnam’s international meteorological stations in the Mekong Delta.The data analysis is done in Excel. Readers can access the data tables in the file Google Spreadsheets.

The authors conducted interviews with two farmers, one local leader, two university professors and two meteorologists, whose opinions are quoted or used as the background information in this story.

This story was supported by the Mekong Data Journalism Fellowship jointly organized by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the East-West center. It was originally published by Dan Viet on 28 January 2022 and has been lightly edited for length and clarity.