Pristine parts of northern Kachin State are under threat as demand grows for high-tech devices that rely on rare earth.

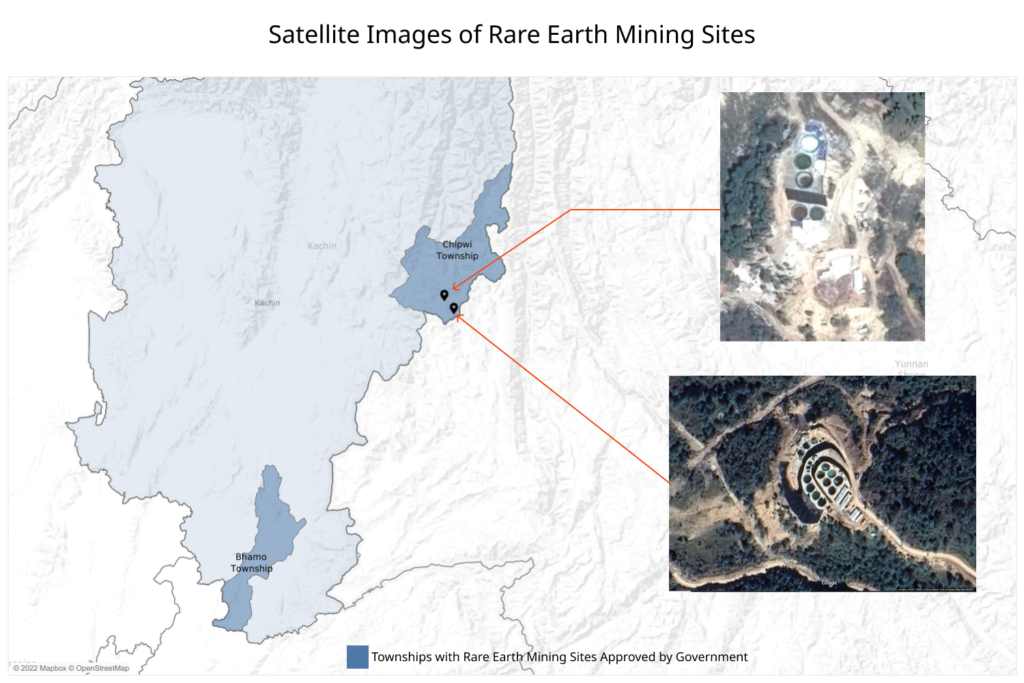

Kachin State’s Chipwi Township in northernmost Myanmar is known for its pristine forests and crystal-clear water.

But 10 years ago, local residents started noticing the patches of land that had been cleared on the lush mountains surrounding their town, which borders China’s Yunnan province. It started with one patch of land, where all the trees were cut down. Then others followed.

Soon locals saw heavy machinery being moved through their town, heading to those barren plots of land. Then workers started flooding in. They excavated the ground and left open pits, many filled with chemically-laced water, in areas once rich in woodland. The water near those sites was no longer clean.

It became obvious at that stage that the newcomers were looking for something underneath the ground – rare earth, which contains elements widely used in high-tech products like smartphones, computer components, electric vehicles and solar cells.

Aung Gam, 45, a resident of Chipwi Township, has seen his peaceful town turn into a bustling mining hub with several thousands of newcomers, many of whom spoke Chinese.

Local people have now linked the rare earth extraction process to the deteriorating environment, which includes polluted water and soil that reduces their crop yields and sales. Some said their concerns had not been adequately addressed by the local and national governments.

“Since after the 2021 military coup, we saw an increasing number of people coming here to work in rare earth mining sites. Under the junta government, the Minister of Natural Resources is fully under the military’s control. Mining activities can be operated freely and unregulated,” said Aung Gam.

Undistributed revenue

Rare earth elements are essential to today’s modern economy due to their high magnetic properties that are needed for producing high-tech devices.

Increasing global demand for rare earth elements makes it a lucrative business in Myanmar, where mining sites are often located in conflict zones such as Kachin State that lacks environmental and tax law enforcement.

The state has been trapped in an on-and-off war between armed groups and the Tatmadaw, as Myanmar’s military is known, for the last six decades, displacing nearly 100,000 people. This years-long conflict has opened the gap for powerful people to exploit Kachin’s rich resources, including timber, jade and its mineral wealth.

Kachin’s rare earth production makes Myanmar the world’s third-largest rare earth producer behind China and the US, according to United States Geological Survey (USGS) data.

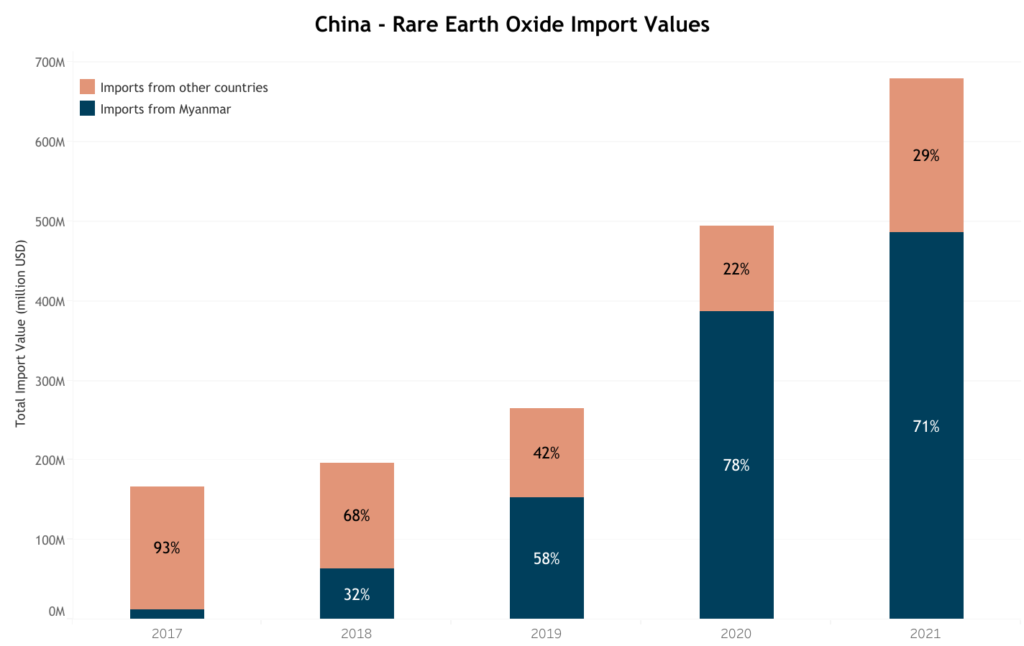

Most of Myanmar’s production is exported to China. Myanmar alone accounted for about 70% of China’s rare earth import value.

According to Resource Trade, Myanmar earned about US$623 million in total from exporting rare earth elements to China from 2011 to 2020.

The annual export value increased from $88,500 to $388 million in the same period of time. The production hiked up from 38 tons to 35,500 tons, a more than 93,000% increase. Data is not available for exports to countries beyond China.

On the other hand, data obtained from China Customs suggested the export volume could be far larger than the initial estimation. Between May 2017 and August 2021, the value of rare earth exported from Myanmar to China was estimated to be worth $1.1 billion.

Half of this amount is equivalent to the two-year education budget for the whole of Myanmar, suggesting the revenue from rare earth exports was not fully distributed to the local population.

Illegal mining surges

Mining activities in Kachin State are particularly active in areas under the control of a militia group the New Democratic Army-Kachin (NDA-K), which was converted into the Border Guard Force (BGF) under the military in 2009. The group leader Zahkung Ting Ying established his own militia group after the conversion.

After the military coup on February 1 last year, illegal rare earth mining has surged in areas under the control of his Tatmadaw-ally militant group. Multiple sources confirmed that members of the group have been involved in rare earth mining companies and profit from the exports to China.

Sources also said some of them had arranged land plots for Chinese businessmen arriving to cash in on rare earth mining. These members were rewarded with revenue shares.

It was also reported that the junta government was seeking more revenue to finance its crackdown on dissidents, raising suspicions that part of the revenue from ore extraction may be directed to the military.

The Irrawaddy, a news website focusing on Myanmar’s politics and current affairs, reported that mining had increased at least five times in Pangwa and Chipwi townships of Kachin State, after a rapid influx of Chinese workers.

“Ordinarily, it would be the Myanmar government’s responsibility to ensure that mining is carried out responsibly and sustainably within its territory,” said Hanna Hindstrom, senior campaigner for Myanmar at Global Witness.

“This is currently made impossible by the fact that the elected government has been overthrown by an illegitimate junta, while mining is predominantly carried out in territory controlled by armed groups and military-affiliated militias.”

Safe haven

A researcher on mining based in Myanmar, who asked to remain anonymous out of safety concerns, said there are 17 types of rare earth elements, including dysprosium and terbium that are found in Kachin State. These two types of minerals are found in only a few countries, making them highly valuable, he said.

Dysprosium is used in various commodities, from data storage applications and lamps to control rods in nuclear reactors. Terbium is used in producing multiple components in electronic devices, including color television tubes and sensors.

“Rare earth mining has a serious impact on the environment if operating without strict regulation. China learned this and tightened its regulation on mining operations in the country,” said the researcher.

“But the demands for the minerals are still there, leading to an increase in rare earth mining in Myanmar where regulations are weak.”

China’s central government noticed the problems of illegal rare earth mining and the environmental damage in the country as early as the 1990s, according to a study on China’s public policies toward the mineral.

The study cited other research on the impact of illegal mining, saying it not only reduces the profitability of the legal firms, but also “damaged the ecology substantially as illegal firms did not treat environmental damage and evaded taxes and fees.”

The Chinese government introduced its first industrial standards for air and water pollution in the rare earth industry in 2011, while launching crackdowns on illegal mining and selling throughout 2010.

That was about the same time that illegal rare earth mining started to take off in Myanmar, where weak environmental regulations provided a safe haven for illegal miners. Between 2016 and 2019, Myanmar’s rare earth production increased by 88 times compared with the 2011-2015 period.

It’s also about the same time that global demand for rare earth elements increased as a result of the growing consumption of high-tech devices.

Harmful activities

The number of rare earth mining sites in Kachin State is unknown.

In 2019, Myanmar’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation granted a license to a local medical company to run 11 mining sites in Chipwi Township, covering 281 acres of land combined, the equivalent to 159 football fields. This reporter contacted the medical company, but did not get any response.

Ko Zaw, a former worker at one rare earth mining site, said the number of sites being excavated in Chipwi and Pangwa townships under the militia group’s control may be higher than official records, based on his observation of the non-stop influx of workers.

He estimates that between 40 and 60 workers are hired for one rare earth mining site. Of those 40 workers, about 15 are Chinese. The head and the technicians at some mining sites come from mainland China, showing the close ties between China and the mining operators in Kachin State.

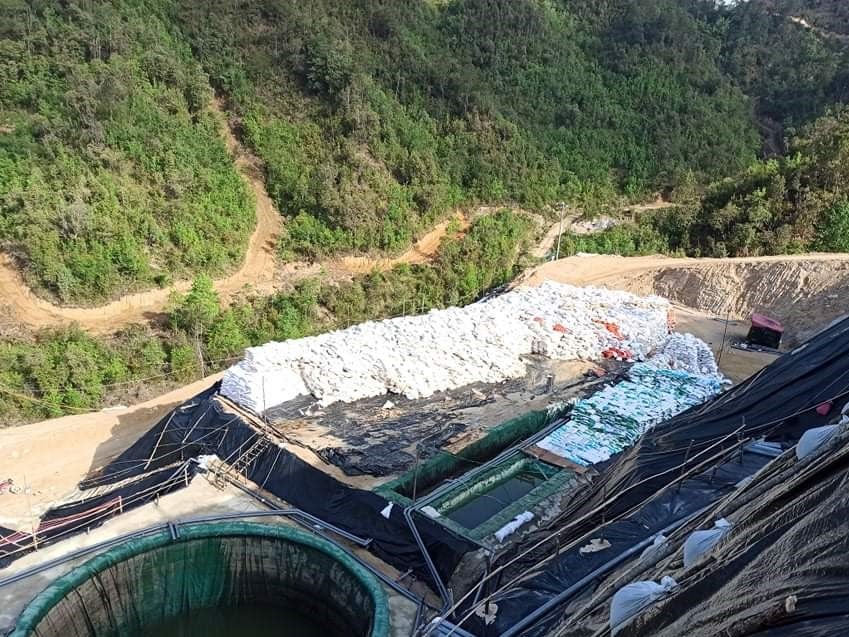

A Burmese worker is paid about 4,500 yuan a month, or about $650. Workers who are tasked with putting chemicals into the leaching ponds are paid more because the job carries more risk and is harmful to the health, said Ko Zaw.

These chemicals, which are called “fertilizer” by local workers, include oxalic acid and ammonium bicarbonate, which are used to separate metals.

When carried out irresponsibly, this mining can harm the environment and human health throughout the process – from land clearance to ore extraction. The leaching pond, where toxic chemicals are applied to dissolve the rare earth, may leak and the contaminated water may get into groundwater if the pond is not properly sealed.

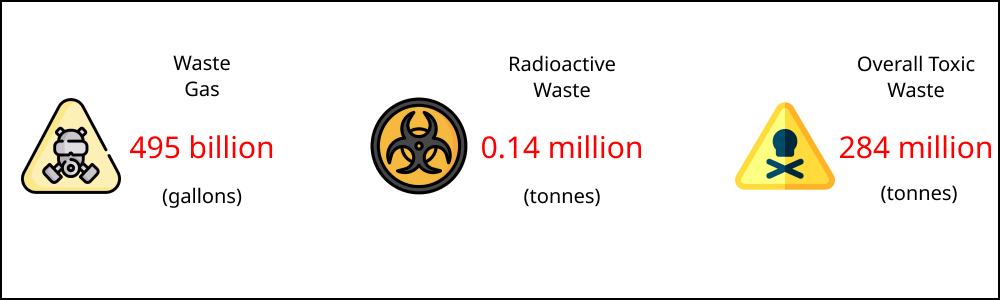

According to the Harvard International Review’s article citing the European Commission’s document, “for every ton of rare earth produced, the mining process yields 13kg of dust, 9,600-12,000 cubic meters of waste gas, 75 cubic meters of wastewater and one ton of radioactive residue.”

A calculation based on these numbers means Myanmar’s rare earth exploitation produced 284 million tons of toxic waste, 0.14 million tons of radioactive waste and 495 billion gallons of hazardous gas between 2017 and 2021.

In recent years, many local communities in Kachin State have voiced their concerns about the unregulated mining, which lacks environmental hazard prevention measures.

The Myitkyina-based Sha-it Social Development Foundation and the Chipwi-based environmental group Laung Byit Khaung told a press conference in 2018 that they had tested water sources near the mining areas and found them to be contaminated with chemical substances.

“We can’t sell fruit from plantations nearby the mining site. Buyers, including the Chinese merchants, are afraid of contamination,” said a local farmer who wanted to remain anonymous.

Some local residents said they had been suffering water shortages and lower crop yields as the mining activities require large amounts of water from communities’ water sources.

Tu Hkawng, the Minister of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation for the National Unity Government – the group of elected lawmakers exiled after the 2021 coup – said it was difficult to pinpoint the exact environmental impact of Kachin’s rare earth mining due to a lack of systematic research.

“Environmental assessment in Myanmar is very weak, partly because we are weak in academics and research,” he said. “We can’t say certainly [that mining activities are causing problems]. It’s what activists are saying.”

Responsible sourcing

With mining activities happening in militia-controlled area, it’s hard for the public to access the mining sites and obtain information about the environmental impact.

“In Myanmar, rare earth mining currently taking place is not only illegal, but completely unregulated and is being carried out in conflict zones by armed groups. There is no way for rare earth mining to take place responsibly in this context,” said Hindstrom from Global Witness.

“No company should be sourcing any minerals from Myanmar in the present context. It is bitterly ironic that so-called ‘green technologies’ necessary to fight climate change may be contributing to environmental devastation for the communities, where the component minerals are mined.”

China had a significant role to play in the supply chains as the country is the top importer of Myanmar’s rare earth, she added. Other players in the supply chains must also ensure that these conflict minerals do not reach international markets.

Yadanar Maung from the Justice for Myanmar group said the country’s rare earth mining is now sustained by the growing global demand for the mineral in high-tech manufacturing.

“Companies and international governments have a choice. The destruction from rare earth mining implicates the major international corporations, who fail to ensure responsible mineral sourcing. They must change [their approach,]” she said.

“International governments must also act urgently in banning the ‘conflict minerals’ in their sales and imports.”

Note: The identities of some local news sources in this story must be undisclosed due to Myanmar’s ongoing political turmoil that creates a hostile atmosphere for dissidents and outspoken local residents.

This story is supported by the Mekong Data Journalism Fellowship jointly organized by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the East-West Center. Its Burmese version was published on Kachinwaves, a Burmese news outlet based in the Kachin State of Myanmar. All data visualizations presented in this story are provided by Thibi.