Only 14 of the rare dolphins remain in Songkhla Lake with their numbers dropping from more than 100 in the 1990s.

Unless action is taken quickly, a pod of rare Irrawaddy dolphins will soon disappear from southern Thailand’s Songkhla Lake, one of their few safe havens in Southeast Asia.

But some locals, including fishermen, are making a determined effort to preserve this rare species. One of them is Uthai Yodjan.

After almost seven decades of watching Irrawaddy dolphins thrive in southern Thailand’s Songkhla Lake, local fisherman Uthai fears these rare, endangered animals are disappearing.

He first encountered a pod of the dolphins in the country’s largest natural lake ― which sits next to a coastal area facing the Gulf of Thailand ― when he started fishing at the age of 15.

There were many of them, he recalled, and he saw them so regularly it seemed like they lived just outside his front door.

His peers often said he knew the most about the dolphins after closely observing their behavior for years. He always knew where to find them and which area of the lake they visited regularly to feast.

But over the past 20 years, he had fewer encounters with the dolphins, and recently there have been fewer and fewer sightings of them.

Uthai is now unsure where to find them. Whenever he is asked by visitors or researchers to show them the dolphins, he drives his fishing boat around the lake and prays for luck.

Quite often, he finds the animals’ lifeless bodies, floating in the middle of the lake or stranded in the shallows.

“I’m afraid they will disappear soon. It will be shameful if the next generations can’t see these animals roaming freely in the lake anymore,” said Uthai.

A recent survey by Thailand’s Department of Marine and Coastal Resources found only 14 Irrawaddy dolphins remained in Songkhla Lake, their numbers declining rapidly from more than 100 in the 1990s.

Their struggle for survival recently raised alarms on social media when Thai marine ecologist Thon Thamrongnawasawat called for efforts to save the remaining ones in Songkhla Lake ― one of a few places in Thailand where Irrawaddy dolphins are found.

His personal Facebook account had nearly 200,000 followers, many of whom weren’t even aware of the animals’ existence until the well-known ecologist posted his appeal.

“We have monitored the population of Irrawaddy dolphins in the lake for two decades, and found their current situation is in ‘extremely crisis,’” said Thon, who joined a research group monitoring marine resources in Songkhla Lake.

“Saving the remaining 14 is the most challenging job I’ve ever done in my entire career. None of the past marine conservation projects in Thailand have had to deal with a very small population of marine animals living in closed water.”

Extinction a high probability

Irrawaddy dolphins are an endangered species and on the red list of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Their population has plummeted in the last two decades due to many factors, including habitat loss and declining food supplies, mainly caused by human activities.

The animals can be found in some coastal areas of South and Southeast Asia, and in three rivers ― Indonesia’s Mahakam River, Myanmar’s Irrawaddy River and the Mekong River in sections running through Laos and Cambodia.

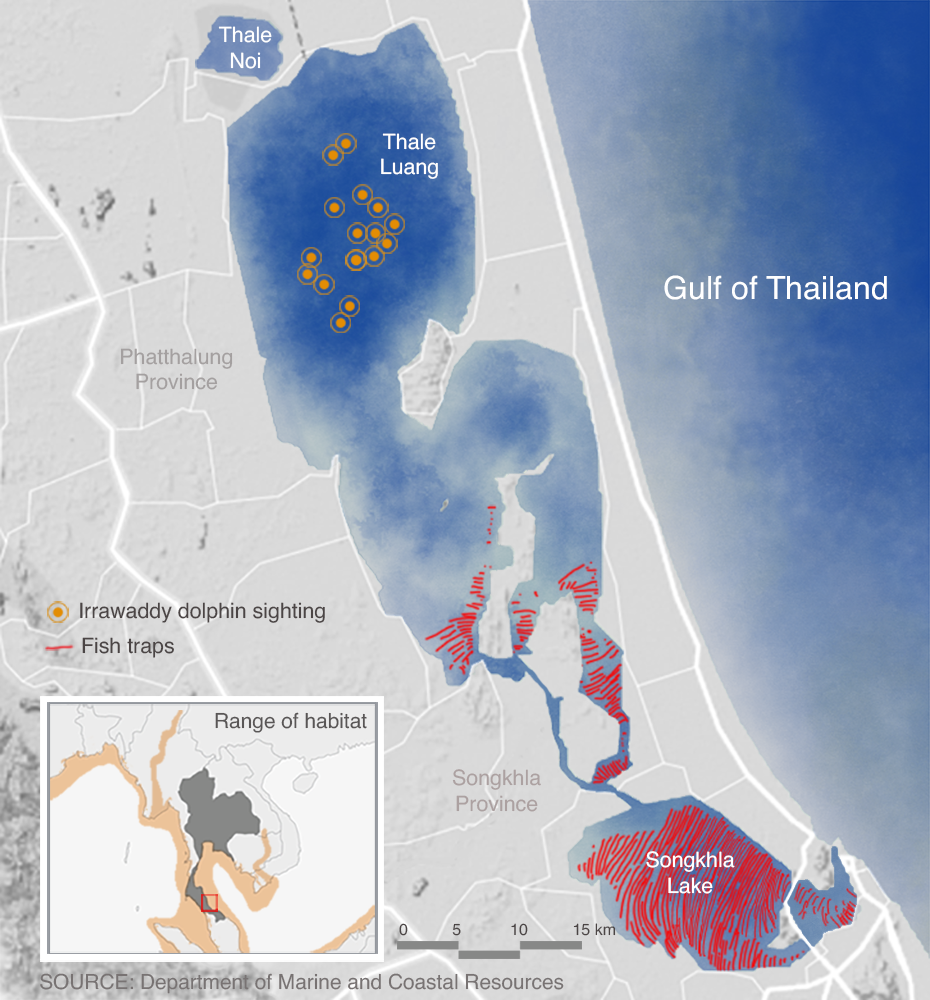

In Thailand, Irrawaddy dolphins have been spotted along the coastline of the western and northern Gulf of Thailand.

While most of the public’s attention has been focused on the pods in the Mekong River, with an estimated 89 individuals in 2020 which were considered “critically endangered” by the IUCN, the population of Irrawaddy dolphins in Songkhla Lake has quietly plunged at an alarming rate.

The animals’ home is in fresh water in the upper part of Songkhla Lake, covering nearly half the lake’s total 1,040-square-kilometer area. This part of the lake borders Phatthalung province and is called Thale Luang, and overfishing and pollution are ongoing problems there.

The southern part, bordering Songkhla province, contains brackish water as seawater floods into the lake through a narrow channel linked to the Gulf of Thailand. This geography makes up the lake’s unique ecology which provides shelter to marine animals living in three types of water ― fresh, brackish and salty water.

Since 2003, researchers from the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR) have tracked the Irrawaddy dolphins in the lake and found the animals’ numbers declined to 27 in 2015, and dropped to between 14 and 20 recently.

Four to five Irrawaddy dolphin carcasses are found each year, making a total of 140 found dead between 1991 and 2021.

About 60% of them died after getting tangled in fishing nets, and 38% were ill, likely due to water pollution and poor health. The other causes of death included food shortages, habitat loss and inbreeding.

Nearly half the carcasses were newborn calves, indicating a declining number reaching the age of fertility.

“With a small population, these dolphins likely inbreed among their pod members. This increases the chances of the calves carrying recessive genes, resulting in poor health and a lower survival rate,” said Ratree Suksuwan, the Director of the DMCR’s Lower Gulf of Thailand office, which oversees Songkhla Lake.

“Inbreeding is one of the reasons we find many carcasses of newborn calves, which were mostly found with no wounds on their bodies or plastics in their stomachs.”

If the situation does not improve, DMCR officials predict the Irrawaddy dolphins will disappear from Songkhla Lake in the next 20 years.

Trapped in nets

Twenty years ago, overfishing was already a major problem in Songkhla Lake.

As fish stocks declined, authorities and local communities came up with the idea of releasing different kinds of juvenile marine animals into the lake, hoping to restore fish stocks and biodiversity.

Among the species introduced were the giant Mekong catfish, an exotic creature for the lake. The heavy weight of these large catfish offered a good payday for many local fishermen, who tried to cash in and increase their income from the lake.

Seine nets, which hang vertically in the water and were sometimes left in the lake overnight, were among the most popular ways of catching giant catfish. However, the nets also trapped the dolphins and prevented them from going to the surface to get air.

Department of fisheries officials estimated there were 1,330 seine nets used in the lake in 2013. Their combined length totals 66.5-kilometers. Just one net can stretch for three kilometers.

Since 2014, the local government started buying the nets from fishermen in an effort to encourage them to switch to sustainable fishing methods. It also drew up dolphin conservation zoning, an area where destructive fishing practices are banned.

But in recent years some fishermen have still been using the seine nets, prolonging an unresolved dispute between local fishermen and authorities. The other problem impacting the dolphins is their shrinking food supply, which has been aggravated by overfishing.

The natural seasonal infusion of salt water from the ocean into Songkhla Lake provides the diversity of species that supply food to marine animals and fish stocks to local communities.

The seawater flows in through a narrow channel at the lake’s southern tip. But recently the water flow has been obstructed by nearly 30,000 fish traps near the mouth of the lake. The traps also contain the slit deposits inside the lake, making the lake shallower and reducing the habitat range of the Irrawaddy dolphins.

The fish traps commonly used by local fishermen are called sai nang. These are a box-like design made of small-size mesh that traps juvenile fish. The traps, when lined up side-by-side in the water, can block marine animals from reaching their breeding sites in the upper part of the lake.

“We have observed the declining fish stocks in the past years. One of the indicators is the lack of fishermen’s presence in some areas of the upper Songkhla Lake,” said Pisit Rakreng, a village headman in Phatthalung’s Chong Thanon subdistrict adjacent to the upper part of Songkhla Lake.

In 2014, people from his community initiated marine conservation zoning, in which they banned fishing to preserve fish nursery habitats. Although a few fishermen snuck into the zone, the fish population increased, as indicated by the fishermen’s presence.

This conservation effort needs participation from local communities settled around the lake, said Pisit, himself a former fisherman. However, he added that each community has its own rules, which don’t necessarily include conservation efforts.

Re-establishing connections

Some action has been taken since marine ecologist Thon launched his social media campaign calling on the public and relevant government offices to save the remaining Irrawaddy dolphins.

Varawut Silpa-archa, the Minister of Natural Resources and Environment, announced that sustaining the animals had been high on the ministry’s agenda.

Conservation measures have been accelerated by the government’s organizations, including the DMCR, which has increased surveillance of illegal and destructive fishing while encouraging local communities to adopt sustainable fishing practices.

The government’s national ocean committee is moving forward with listing Irrawaddy dolphins as one of Thailand’s ‘reserved species,’ or species with endangered status. The list includes 19 animals at risk of extinction, including the dugong, leatherback turtle, Bryde's whale and Omura's whale.

If the move succeeds, authorities will be able to implement strict measures to tackle the threats to Irrawaddy dolphins. A long-term solution would involve expanding research on the animals’ breeding and restoring their food supplies.

“Little research relating to Irrawaddy dolphins’ breeding has been done in Thailand. We urgently need more for implementing an effective breeding program. It will take time to achieve. It will also be challenging. But we will get closer to success if we start now,” said Thon.

At the local level, the need to get local communities involved in conservation is still a challenge, as local people have lost their connection with the Irrawaddy dolphins due to their rare sightings.

To re-establish that connection, fisherman Uthai and his friends formed the Irrawaddy Dolphins Conservation Club in 2006 to raise awareness of the animals among local fishermen.

With the participation of 25 fishermen, club members have encouraged other local fishermen to shift to using less destructive gear and report to authorities if they find a dolphin’s carcass. But some fishermen avoid disclosing information about the dolphins, fearing it will lead to authorities banning fishing.

One of the emerging ideas to solve this dilemma is to integrate the animals into local eco-tourism, which can provide alternative incomes for local fishermen and help them move away from destructive fishing practices.

Some local communities have started eco-tourism businesses in recent years. Pisit’s community, for example, offers tour packages that include watching the sunrise on a floating deck in the middle of the lake and building artificial fish habitats.

“If we can bring Irrawaddy dolphins into local tourism, it will be beneficial for local communities and conservation efforts,” he said. “Currently, we can’t promote dolphin watching in our tour packages, because we can’t guarantee tourists that they will find the dolphins during the trips.”

This brings the issue back to the priority of growing the Irrawaddy dolphins’ population.

“This is not the job of one player. If we can get every stakeholder to participate, then we can have hope,” said Uthai.