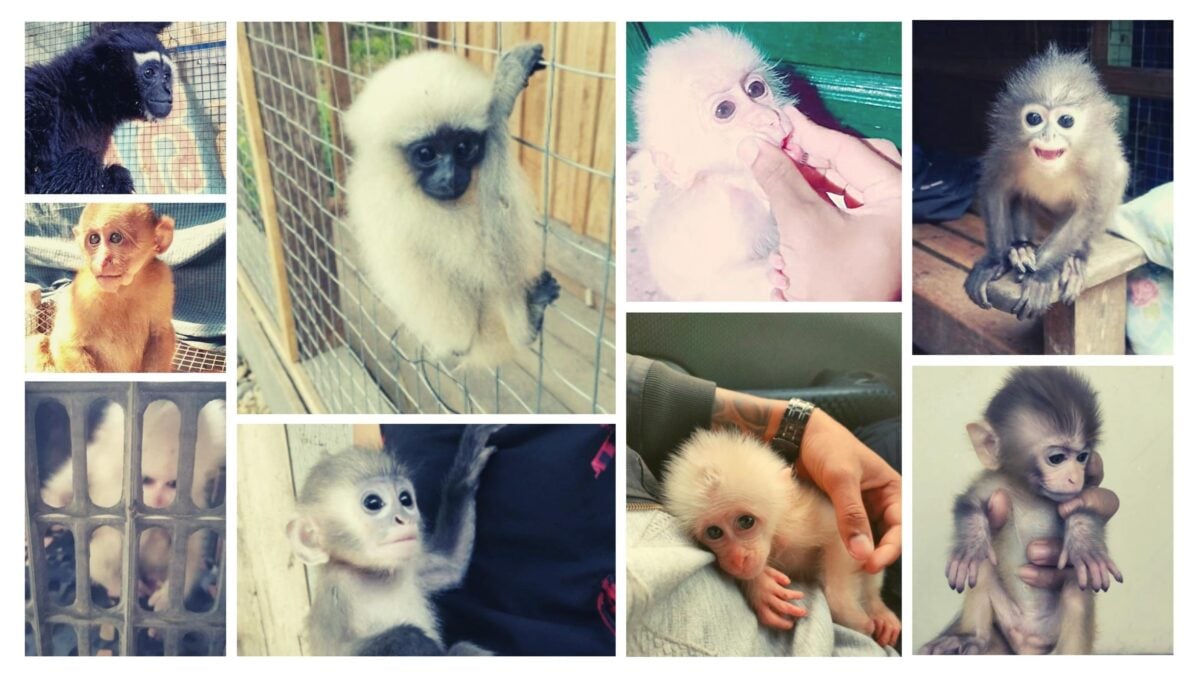

Online trade of wild langurs and monkeys has drastically increased in the absence of rule of law.

CHIANG MAI, THAILAND ― Local demand in Myanmar for wild langurs and monkeys as pets has been increasing, driven by a booming online wildlife trade and weakened law enforcement since the 2021 military coup.

In one startling example, Ma Saw, a white-collar worker living in Yangon, was browsing the internet on her phone after a long day at work. Her eyes caught a post and pictures of an infant macaque “for sale” in a public Facebook group.

Reading through the comments, she noticed that no one wanted to buy the baby primate as it had lost its right hand. Many members of the group demanded perfect-looking animals, with no injuries and in good health.

“I could not stand their comments. I felt sorry for this poor little one. I reached out to the seller via direct message and made a quick decision to buy it. I believe the monkey lost his mother and was wounded while being caught by the seller,” said Ma Saw, who asked that her real name not be used.

She paid 70,000 Kyat, or US$38, for the macaque, which she named Shwe Ky, meaning lucky. The seller put it in a plastic container and sent it to her via a public bus from the country’s northern Kachin state. It took about 12 hours for the animal to reach Ma Saw’s home.

Shwe Ky was very fatigued after the trip. Ma Saw immediately took him to a veterinarian, who suggested she give intensive care to the suffering baby monkey.

Ma Saw is one of many local wildlife buyers, whose motivations are varied. Their transactions with the sellers have fueled Myanmar’s online illegal wildlife trade in recent years, as local access to the internet and mobile banking grew substantially.

Raising baby monkeys as pets is one of the most common things the buyers do, and many ask for a specific species from the sellers in social media groups.

Many bought monkeys because they felt sorry for the animals, as was the case with Ma Saw. Others think that owning a wild animal is cool and symbolizes their wealth, a trend that has been noticed by Myanmar’s social media users.

Social media posts with wild monkeys, especially posts showing the monkeys being trained as pets, often get a lot of viewers on TikTok and Facebook, the most popular social media platforms in Myanmar.

Stress from the Covid-19 pandemic and the ongoing political turmoil have driven many people to seek new pets, according to local opinion.

A growing trade in wildlife

The unsustainable and illegal wildlife trade is the second-biggest direct threat to species after habitat destruction, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

In April, the WWF released a study showing that Myanmar’s online illegal wildlife trade inside the country increased by 74% from 2020 to 2021.

The organization tracked more than 11,046 animals from 173 species sold online in 2021, up from 143 species the year before. Among them, six species were listed as “critically endangered” on the IUCN Red List. Seven were marked “endangered” and 33 “vulnerable.”

About 96% of the posts were for live animals and more than three-quarters were for animals taken from the wild.

Posts for mammal sales saw the biggest jump in numbers, from 169 to 576 in 2020 and 2021, a 241% increase. The most popular mammals were various species of langurs and monkeys, often bought as pets, according to the WWF report.

Those included the dusky leaf and Shortridge’s langurs, as well as the stump-tailed and northern pig-tailed macaques.

Mekong Eye also found offers to sell Popa langurs, a newly discovered primate species exclusively found in Myanmar, on Facebook groups. The animals are critically endangered and estimations of their numbers range from between 200 and 250 still in the wild.

These animals are traded freely in open groups on Facebook, where members can advertise and sell wildlife without facing any legal action.

Many sellers don’t use their authenticated accounts but create new accounts for making deals in the wildlife trade. They usually use video calls to potential buyers to show the conditions of the animals.

“Potential buyers usually reach out to me via Facebook direct message. They want to know about the health of the animals and find out if the monkeys have ‘friendly behavior,’” said a seller based in Yangon, who asked not to be named.

“I offer a cash-on-delivery option to buyers who can pick up the animals near my place. If the buyers live in other cities and towns, the transaction will be made online. The animals will be delivered by public bus.”

Based on interviews with sellers and buyers, baby monkeys are in high demand and can be sold within one to three days after being advertised on social media.

The prices range from 70,000 to 300,000 Kyat, or $35 to $150. The price can go up if the monkeys have been trained to act like humans.

A lack of human resources

On February 1 last year, Myanmar’s military, led by General Min Aung Hlaing, staged a coup and seized power from the National League for Democracy’s elected government ― turning the country into an authoritarian state with a weakened rule of law.

Since the military coup, local media outlets have reported the accelerated exploitation of natural resources through multiple activities, including mining and deforestation.

When it comes to the wildlife trade, hunters have taken advantage of the lack of law enforcement to hunt and trade protected animals, mostly without having to face any consequences. The coup has also halted Myanmar’s progress in tackling the wildlife trade.

Ko Linn – not his real name – a former staff member of Myanmar’s Department of Environment and Wildlife Conservation, said the illegal wildlife trade had thrived because the post-coup government did not have enough human resources or budget to tackle the issue.

He left the department after working there for 12 years and joined the civil disobedient movement, along with thousands of government employees, including military personnel, police and civil servants.

These former officials resigned from their positions to show resistance to the new junta government. Many were arrested and detained by the military.

“Before the coup, there were collaborations across government institutions, NGOs, civil society groups and local people to preserve our wildlife, especially those being threatened and endangered like the Popa langur and pangolins,” he said. “But all that cooperation has stopped now.”

In the juridical sphere, the enforcement of the Conservation of Biodiversity and Protected Areas Law has been weakened due to a lack of government personnel and a declining rule of law.

That law is the upgraded version of the 1994 wildlife conservation law, which was amended in 2018 to enhance conservation efforts with support from the elected government and civil society.

Under the law, the protection of wildlife species was classified into three categories based on their endangered status ― “completely,” “normally” and “seasonally.”

Any individual who kills, hunts, possesses or trades completely protected species, or their parts or derivatives, will be sentenced to between three and 10 years in prison.

However, while the law is still in place, the enforcement is not. The military junta has turned the juridical system into a tool to criminalize dissidents, leaving little space for legal action against other crimes, including the wildlife trade.

“The political crisis has further hampered environmental regulation and law enforcement. In addition, the ability to trade anonymously online means that people buy and sell with impunity,” said Nay Myo Shwe, head of the Wildlife Program for the WWF Myanmar.

No happy ending

Apart from the political turmoil, some other factors have been linked to the hike in the online wildlife trade inside Myanmar.

“Some people keep wildlife as pets because they believe the animals project a superior image of themselves. Many are not aware that the wildlife trade is illegal, or know it but take advantage of the absence of effective law enforcement,” said Nay Myo Shwe.

“Apes are intelligent, sensitive and highly social animals, making [the buyers] fascinated [by their behavior.] The infants are also appealing to them. But baby primates need their mothers who teach them the skills they need for survival. Depriving primates’ contact with their own members is extremely cruel and distressing for them.”

Having contact with wildlife also increases health risks for humans as the animals can carry diseases that are deadly to people. Lessons should be learned from past health problems caused by zoonotic diseases, including SARS, MERS, swine flu, avian flu and Covid-19, warned Nay Myo Shwe.

Ma Saw, the buyer of the infant macaque, wanted to release Shwe Ky into the wild. But she has given up on that idea because she is certain the monkey would not survive without learning skills from its mother.

Shwe Ky was still alive while this article was written. But others may not be as lucky.

Wildlife buyer Ko Khaing Min – not his real name – bought a two-month-old monkey online in April, simply because “it was cute.”

“She was very vulnerable when I got her. She died of diarrhea after two months of staying with me. It’s better not to raise a wild monkey if you could not give it intensive care, and it’s costly,” he said.

This story is supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network

All illustrations are created by Paritta Wangkiat, editor of Mekong Eye. They depict how monkeys and langurs are being treated, based on the social media posts and the author’s interview with wildlife buyers and sellers.