A Vietnamese journalist’s investigation into illegal sand mining in the Mekong Delta prompted Deputy Prime Minister to issue a letter, ordering authorities to tackle the issue.

Vietnam’s Mekong Delta has been experiencing severe erosion for the past several years – a matter that’s widely reported and well known to the public and government officials. It is also well established that one of the main culprits is excessive sand mining in the area to meet the country’s construction needs.

Official sand mines have been able to meet only 40-50% of nationwide demand since 2016. In the Mekong Delta alone, by 2025, an estimated 400 kilometers of new highways are going to be built, which will require hundreds of millions cubic meters of sand.

Meanwhile, the official sand reserves of the five Mekong Delta provinces from 2014 to 2024 total just 95 million cubic meters (approximately 152 million tons of sand). Illegal dredging continues to this day, as do bloody clashes between the sand mafia and residents at risk of losing their homes and farms to erosion.

When journalist Le Dinh Tuyen was awarded the Mekong Data Journalism Fellowship by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the East-West Center in April 2021, he decided to investigate sand mining in the delta somewhat differently.

He went looking for data on a scale and breadth none of his colleagues has done before.

The result was a series of three stories published in April 2022 in Thanh Nien newspaper, published in Vietnamese here, here and here; with an English version on the Mekong Eye website. The story was then republished by The Third Pole, Eco-Business and translated into Italian.

It revealed that over the past decade, five Mekong Delta provinces have issued permits to mine around 71 million cubic meters (114 million tons) worth of sand reserves.

This statistic was then linked to other alarming trends in the area: erosion along 500 kilometers of riverbanks and the coast, and 20,000 households having to relocate due to subsidence risks, which has cost the government trillions of dong (or millions of dollars).

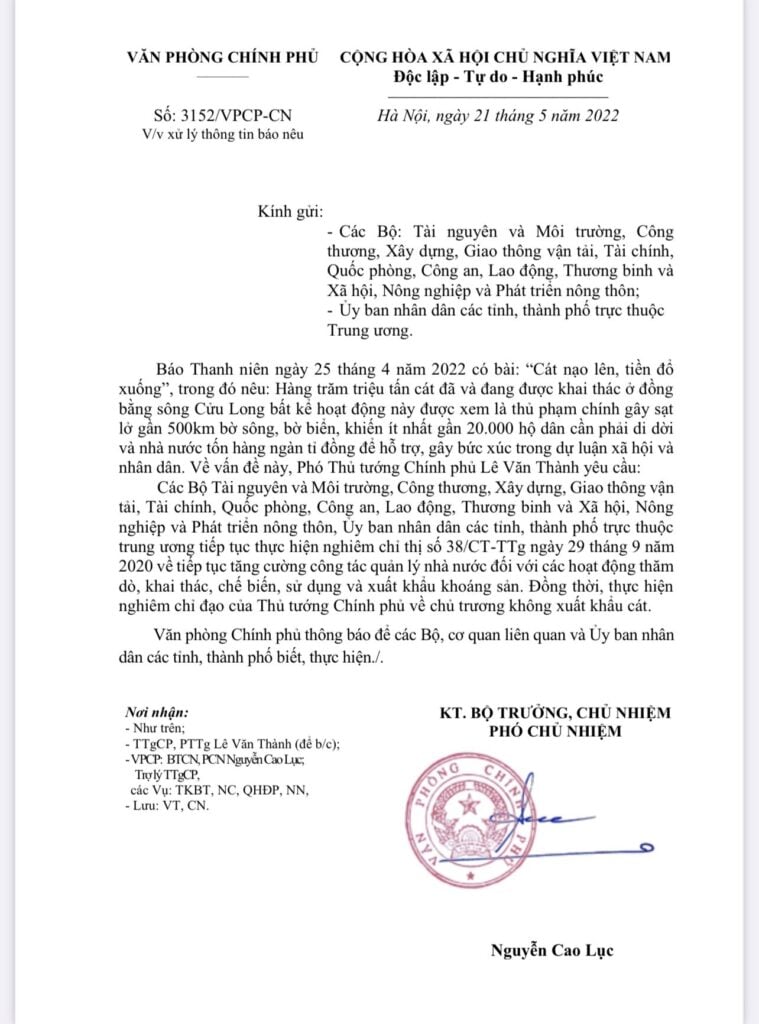

A month later, on May 21, Deputy Prime Minister Le Van Thanh issued a letter via the Government Office which referred to Tuyen’s article and cited the above findings.

The story, “has angered the society and the people,” said the letter, addressed to nine relevant ministries* and local governments across the country.

It went on to ask the agencies to strengthen oversight over exploration, mining, processing, use, and export of minerals while adhering to the country’s ban on sand exports.

“When I received it, I thought, ‘great!’. I felt that my article could reach and make the most senior level in the government care about the issue. And that was my aim too,” said Tuyen.

In the aftermath of the letter, Tuyen received anecdotal reports from sand buyers that local governments have strengthened their crackdowns on illegal sand mining, fining more illegal activities than before. EJN has been unable to verify this observation more systematically due to lack of data.

“I am very happy to see the issue that I highlighted getting so much attention,” said Tuyen of the news and congratulations he has received from friends and experts in the field.

“When you paint the big picture of the problem, connect the dots on how erosion, sand mining, local life and government are all inter-linked to development, it begs the reader to think: ‘ah, we need to care about this and push for change’.”

Nguyen Huu Thien, a renowned independent expert on environmental issues in the Mekong Delta and one of Tuyen’s sources in the story, said that before Tuyen, “no one analyzed the issue as systematically, with supporting data that made the story highly convincing – which is why the government took notice.”

Thien offered an analogy: “The government is like a boat; the public is like water. If you raise the public’s awareness, you raise the government up, the government will follow.”

He said that when Tuyen was studying as part of the Mekong Data Journalism fellowship, he complained about the workload a lot but, in the end, it paid off: “It was very worthy of congratulations.”

Tuyen was part of the first cohort of fellows from Cambodia, Laos Thailand and Vietnam who received intensive training over 6 months on how to find, collect, visualize, and tell a story with data.

“In the beginning, I even thought of quitting because of my not-so-good English,” Tuyen said, recalling his fellowship experience. “I had to push myself a lot. On many occasions, I couldn’t follow the course, didn’t understand what was going on.”

But Tuyen persevered. He shifted his mindset to view the fellowship as an opportunity to produce a good story. The availability of four different mentors also played a role in motivating him.

Looking back, Tuyen said the fellowship had “a very big impact” on him, and how his sand mining story turned out. “It changed my view on how to conduct reporting,” he said.

Before that, he didn’t know much about data journalism. His old approach was simple: interview sources and ask relevant authorities for any data they might have.

“If I were to follow my old methods, it’s lazy. But by scraping, I realized, oh, the data is out there, out in the open, and I managed to gather a lot of data,” he said of how he pulled and combined information from five Mekong Delta provinces to highlight sand mining as an inter-provincial issue.

Tuyen’s old reporting habits reflect the Vietnamese media’s reactive approach to how sand mining is reported in the news.

Before Tuyen’s story “if the media wanted to discuss a certain topic, they had to wait for a news event that they could follow,” said Thien, the Mekong Delta expert who often gives interviews to journalists. “No one took the lead like Tuyen. Tuyen’s story was the catalyst that triggered public discourse.”

Indeed, Thien observed an increased interest from mainstream media in sand mining after Tuyen’s story came out, reflected in the number of recent stories and interview requests he has received.

“Tuyen’s story came out of the blue, became a trend setter, very surprising. After that came Tuoi Tre [Young People newspaper], Nong Nghiep [an agriculture newspaper], VnExpress, and others. [Tuyen’s story] heated up the news media. Tuoi Tre newspaper followed up with a story on how it is harder to buy sand than gold,” he shared.

These local media reports have built upon and expanded Tuyen’s reporting to discuss how scarce sand is and where the country can get enough sand for its urgent infrastructure needs.

In late June, Vietnam National Television produced a special documentary on sand mining in the Mekong Delta, reiterating Tuyen’s findings. Tuyen himself was interviewed for the documentary, which also mentioned the government letter.

The team at WWF Vietnam, who have an ongoing project on sustainable sand mining in the Mekong Delta, echo Thien’s observation.

Their internal analysis of news articles on sand mining published since 2017 from 10 major Vietnamese newspapers shows that the reports are mainly about illegal mining activities and resulting riverbank and coastal erosion.

“However, perhaps due to a lack of access to specialist scientific research, the media has reported little on other serious consequences of sand mining – such as on local livelihoods, changes in river morphology that have led to riverbank and coastal erosion, delta subsidence, increasing saltwater intrusion, threatening food security, ecosystems, and biodiversity of the whole delta,” Ha Huy Anh, national project manager of IKI Sand Mining Project under WWF Vietnam said in an emailed statement.

Tuyen has observed a similar gap, albeit from a different perspective. “Simply describing what happened no longer satisfies readers, especially the knowledgeable ones,” Tuyen said.

This is why he was excited to learn from the fellowship better ways to simplify, analyze and attach meaning to the statistics, so that readers could understand the scale of the issue at hand. The 20,000 households that need to be relocated due to subsidence risks, for example, are equivalent to establishing 57 new villages.

The letter from the deputy prime minister is certainly a significant development, as Tuyen, Thien and WWF have all noted. But the path to achieving sustainable sand mining has a long way to go.

“For too long, sand mining has been looked at from a provincial perspective. It has to be viewed at a regional, inter-provincial level,” said Thien. “Now that this awareness has reached such a high level [of government,] I hope for a more comprehensive policy.”

Thien stresses the need for more reporting and analysis on alternatives to sand, as well as more human-centered stories on how locals, businesses and the authorities are struggling to deal with the consequences of excessive extraction of sand.

It is significant that it caught the attention of the highest level of government, but “to achieve substantial change, we need time and other tools,” said Tuyen.

“Once we’re aware that sand is no longer going to be replenished, we need to start looking for alternative materials,” said Thien, stressing the need for management of sand mining at a regional level.

“Following the [government’s] letter, the government will need to calculate how to better manage the issue. People need to consider the river as a whole. If you mine sand in one area [of the river,] other areas will be eroded too.”

Anh of WWF Vietnam agreed: “Solving the paradox of sand mining in the Mekong Delta is a complex issue that requires multi-sectoral and multi-level coordination based on science.”

He encouraged the media to play a more active role.

“Using the power of their pen, combined with investigative skills, diverse sources and the ability to convey information to many different stakeholders, from policymakers and decision-makers at central and local levels, to businesses and the public across the country, journalists play an important role in promoting awareness and behavior change,” he said.

Tuyen intends to continue doing exactly that. He reiterated that data journalism not only increased the quality of his story but would “also gradually increase the quality of the newspaper” where he works.

“I’m planning two to three new stories, but first I need to re-learn [data journalism,]” Tuyen said with a laugh.

“During the fellowship, mentors were available to help. I could ask questions. I’ve already made the first step, there’s no reason for me to go back to how I used to do stories before. Of course, I have to continue.”

Note: Deputy Prime Minister Le Van Thanh’s letter was addressed to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry of Construction, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Finance, Ministry of National Defense, Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development; and the People’s Committees of provinces and centrally run cities.