In a world awash with bad news, updates from home leave a particularly bitter taste.

Of course, I’m emotionally invested, but the Myanmar military’s relentless assaults, both physical and mental, on its own people also laid bare the pure malevolence at its core.

From the bombings and burning of entire villages to the torture and extrajudicial killings of its citizens, the military dictatorship is dragging the whole country down with it.

What makes it even more excruciating is how the international community seems unwilling or unable to provide tangible support beyond releasing statements condemning the army’s conduct.

It feels like the world has forgotten about Myanmar.

I wrote in early May that the coup was a loss not only for democracy but also for environmental action. The isolated regime would once again turn to nature to feed its greed and tighten its hold.

Well, 19 months on, we’re only starting to get glimpses of how rapacious the army and its allies have been.

Activists and communities protecting their ecosystems are at the front lines of the struggle. They are particularly vulnerable because their work is also linked to other key issues such as human rights and land tenure security.

“I have heard over the past few weeks cases of people being arrested for conducting environmental awareness raising sessions, community members being shot for opposing mines by militias, and also several cases of people being threatened with death by ethnic armed organizations and militias for asking questions about extractive operations,” said Jack Jenkins Hill, an environmental researcher.

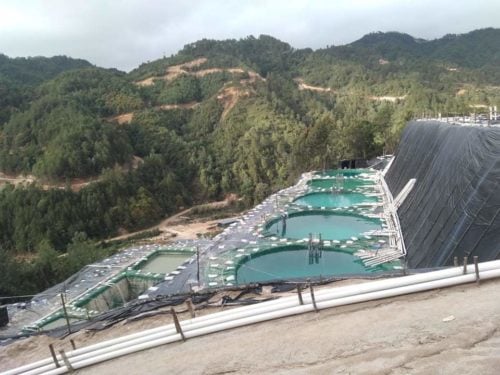

Advocacy group Global Witness documented similar problems in a report it released earlier August on rare earth mining in Myanmar. It documented 2,700 rare earth mining sites in the country’s north as of March 2022, covering an area the size of Singapore.

The mines have enriched military-linked militias who “threatened to shoot local community members if they refused to give up their land to make way for new mines,” it said.

Myanmar’s environment hit by rare earth mining boom

Pristine parts of northern Kachin State are under threat as demand grows for high-tech devices that rely on rare earth.

Difficulties for environmental defenders are “at the highest level,” said the chair of the All Burma Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance (ABIPA), a network of more than 30 indigenous civil society groups across Myanmar. The chair requested anonymity for safety reasons.

The coup regime is targeting environmentalists and their families, while internet and mobile phone limitations and skyrocketing commodity prices threaten their work and livelihoods, they told me.

“Not only the coup makers but also their agents are actively involved in natural resource extraction in various means such as gold mining, logging, trade in wildlife, artifacts, etc. The lawlessness that now permeates these activities creates a particularly dangerous environment for campaigners,” they added.

In an article for the Frontier Myanmar media outlet, another activist said: “Mining projects are operating but we cannot engage in dialogue with the companies anymore. They do what they want. In the past, we could go and talk to them if the water was polluted or if they were causing problems for us. Now we don’t know who we can report to.”

“More than 21 environmental defenders from our networks have been arrested, and everyone else has had to go into hiding or been forced to fight for their lives and their futures,” the activist added.

For all these challenges, however, I want to emphasize that Myanmar is not a failed state. There are things the international community can and should do, precisely because the junta wants the outside world to give up on Myanmar.

So, what can the international community do? I have five tips for them.

1. Support local actors

Conditions on the ground are difficult, but there are local organizations that are still working on environmental issues, either very quietly within Myanmar or across the border in Thailand. International organizations should work with them.

“There are ethnic administrations such as the Kawthoolei Forest Department that are still doing conservation work, but have very limited access to funds, and many other organizations that have relocated to the forest, where they are continuing to work on small-scale conservation work or on monitoring new extractive projects,” said Jenkins Hill.

Technology such as remote sensing will help with environmental monitoring. Value chain tracking support will keep governments and companies accountable, but they tend to be either too costly or not available, he added.

The chair of the ABIPA also said they need all forms of support, from technical to financial.

For example, they need help with collecting, processing and presenting data so they can be more effective advocates for the environment. They also need space at regional and international events so their voices and concerns are heard.

2. Make support flexible and creative

Please do not ask the environmental defenders, many of whom are running for their lives, to fill in pages of grant applications and give details of their theory of change. Also, some of them may have links with ethnic armed groups, but that fact alone should not stop you.

We often hear the argument that donors cannot fund projects in-country because of sanctions, restrictions on banks or that the banking system is not functioning properly.

But let us not forget that Myanmar’s opening is a recent phenomenon ― it only really started a little more than a decade ago. Donors supported projects before this. They can do it again.

Also, be aware of the context in which the groups are operating. “If donors can reduce administrative burdens, it will also be very helpful because these requirements can be used as evidence to arrest or harm [environmentalists,]” said the ABIPA chair.

3. Don’t only support activities, but defenders too

I think this is self-explanatory. But I will emphasize again that in Myanmar, environmental defenders are often also defending human rights, indigenous rights, land rights and gender equality.

4. Do not outsource the work to ASEAN

ASEAN has been so ineffectual. It would be laughable if it were not for people dying every day because of their inaction. Sure, pressure them to do more, but western countries need to take leadership roles too.

5. Enforce your laws and actions

There is little point sanctioning military-owned conglomerates or senior junta leaders if resources from Myanmar are still reaching you.

A case in point is Forest Trends’s report in March, which showed how more than 20% of Myanmar’s timber exports last year landed in the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union despite their governments’ sanctions on mining and forestry products from the country.

What the military wants is for the world to forget about Myanmar so they can do whatever they want with it.

History has proved that they are the biggest threat not only to the people of Myanmar, but also to its ecosystems. We cannot let them go on destroying both.