Gold rush in Kachin state puts the country’s largest freshwater inland lake at risk of disappearing.

KACHIN, MYANMAR – Illegal gold mining is threatening Myanmar’s largest inland freshwater lake – which ethnic people in Kachin state depend on for their livelihoods – due to the increasing demand for the precious metal as the country’s economy teeters towards collapse.

U Aung Ko, a 60-year-old ethnic Shan resident in Ma Mon Kaing village at the southern tip of Indawgyi lake, often uses the lake’s water to cool himself down during the heat of the day.

He grew up in the peaceful surroundings of the lake, like the more than 35,000 people living in 13 landlocked villages around it, and has used the lake’s water and resources to survive.

Indawgyi lake is a designated UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in Mohnyin Township in the southwest of Kachin State. The people living around it are from the Kachin and Red Shan ethnic groups who mainly farm and graze animals around the lake while fishing in the water – their primary source of protein.

But in the past few years, U Aung has noticed that the water in the lake has become muddy and shallower. He believes the lake is gradually drying up.

“The depth of water [in the lake near my village] was 16 meters recently. It was nearly 27 meters 10 years ago. This shows the significant volume of sediment accumulated at the bottom of the lake,” he said.

Beyond his village are hills with streams where he can hear the noise of heavy machinery working. The land along these streams is being unearthed by gold miners, mostly in small-scale operations, sending sediment and wastewater down to the lake.

The miners work relentlessly to extract gold from ore – which mainly ends up in Myanmar’s local gold market, which has boomed since the military coup in February 2021.

Gold sales spiked as consumers rushed to withdraw cash to purchase gold due to the rapid depreciation of the Kyat and the Central Bank of Myanmar’s policy to freeze foreign currency held at domestic banks.

As of October, the price of gold in the country rose nearly 50% compared with the price in the month of the coup as the demand for gold and hoarding increased.

The rising demand for gold in the post-coup era has happened along with the surge of gold mining in Kachin state and around the Indawgyi lake. Many of these mines are operated illegally and without environmental impact mitigation.

Freshwater ecosystem under threat

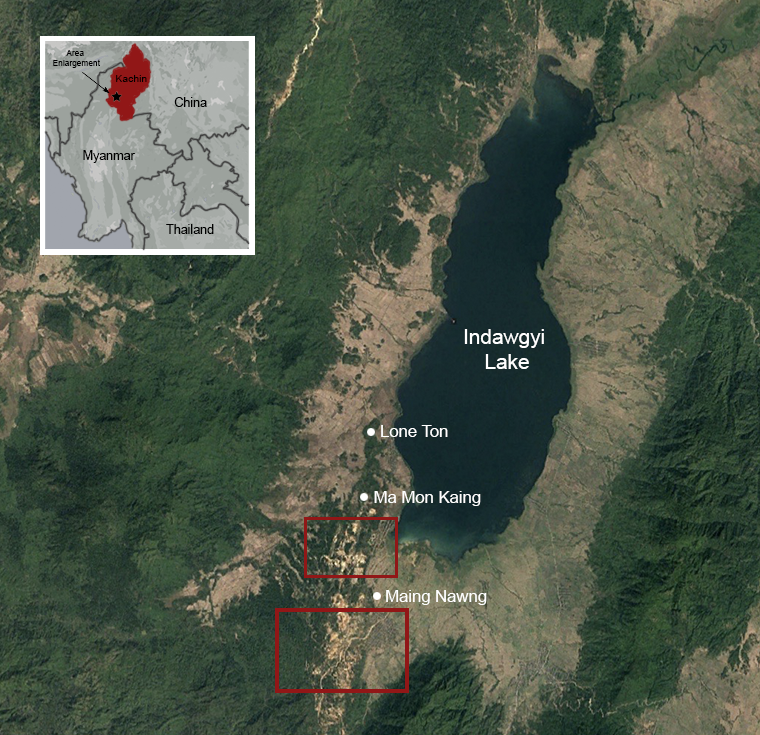

Illegal gold mining has been widespread in Mohnyin Township, especially in Maing Nawng, Lone Ton, and Ma Mon Kaing villages, which are along the Indawgyi lake.

In January, the Brandenburg University of Technology released a study pointing out that extensive artisanal small-scale gold mining, together with population growth and intensified agriculture and fishing, has put environmental pressure on Indawgyi lake.

The study focuses on gold mining along tributaries known as Hkaung Tung Hka Chaung at the southern part of the lake.

It shows that the expanding gold mining in the area has led to an annual input of 133,000 tons of sediment into the lake, and the mining is associated with the destruction of flood plains and forest areas that result in soil erosion.

The complete filling of the lake basin would take between 3,600 and 5,400 years, if the sediment load would stay constant, according to the study.

The rampant gold mining threatens the lake’s freshwater ecosystem, which supports local people and provides a habitat for more than 600 species, according to figures from UNESCO. More than 160 bird species have been found in the area, including many globally threatened migratory birds, as well as white-rumped vultures and slender-billed vultures.

This ecological value led UNESCO to declare the Indawgyi Lake Wildlife Sanctuary a Biosphere Reserve in 2017. It covers an area of 73,600 hectares of forest, wetland and open lake, which accounts for 16% of the area of Southeast Asia’s third largest freshwater lake.

But as the mining intensified in the post-coup era, many local people and conservation groups are concerned that Indawgyi lake could eventually disappear if authorities turn a blind eye to this man-made disaster.

“We estimate that the lake has lost around 260 hectares of its freshwater area in the past few years,” said Ko Zwe Ko Ko, a leader of Inn Lovers Group, a local environmental protection organization based in Kachin state.

“Our survey found that nearly 800 hectares of the lake has already been covered up by sediment and mud.”

A local environmental group recorded a total of 191 excavators being used for illegal gold mining in the area, a huge increase from the 45 that were there before the coup.

The same group also used Google Earth satellite images to estimate the mining area around the lake, which has expanded to about 6,000 acres. Some parts of that land is covered by large mounds of mining residue.

Local farmers abandoned or sold more than 50 acres of upland farms in 2022 due to the impact of gold mining, which included mudslides and damaged roads. More farmers are considering leaving their land if the impact worsens.

“The mining causes soil degradation in our farmland and makes our crop yield decline,” said Hkawng Dau, a farmer in Maing Nawng village.

“We are worried about the fish we eat and question whether it contains mercury [used by small-scale gold miners to extract gold]. We have no choice but to consume fish from the lake despite our fears for our health.”

Another villager, asked not to be named, said some residents had itchy skin or rashes after bathing in water from the lake. Drug problems have also emerged as workers use drugs to help them labor for long hours in the gold mines.

Outlaw territory

From March 2016 to May 2020, Kachin State’s Mining Department gave permission for individuals or companies to operate 223 small-scale gold mining plots and 262 artisanal gold plots in 11 townships, according to a statement of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation.

It did not give permission for any mining activities near Indawgyi lake at that time, when Myanmar was governed by an elected government led by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy.

A mining monitoring mechanism was put in place, including regular mining site inspections by the Sub-National Coordination Unit – a tripartite group formed by the government, businesses and civil society organizations. But this mechanism was forced to stop after the coup.

Enforcement of the existing mining law has also been absent. Kachin State’s law mandates small-scale and artisanal miners can carry out mining activities away from water sources – at least 90 meters. It also includes instructions for mining methods that do not harm the environment.

“No one follows the rules and regulations now,” said U Zaw, a resident of Ma Mon Kaing village.

“Given the current political situation, people do not dare to file complaints to the military government as they fear potential death threats from those in the mining business. We have to be afraid of all-powerful people. We are like orphans to them.”

Due to the political instability, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) – which promotes open and accountable management of the oil, gas and mining industries – announced it was suspending its work in Myanmar. This left the industries unchecked by outsiders.

Tu Hkawng, the Minister of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation under the National Unity Government (NUG), said illegal mining activities are often carried out in the “ungoverned” territories.

Some territories in Myanmar are not under the control of any political groups, a result of collapsing governance and administration after the coup that resulted in some places becoming outlaw areas.

The State Administrative Council (SAC), established by the junta after the coup, fully controls 22% of 330 townships across the country, according to a paper released in September by the Special Advisory Council of Myanmar, an independent group of international experts working to support people in the country.

These townships make up only 17% of the country’s land mass.

On the other hand, the NUG claimed its armed wing, the People’s Defense Forces and allied ethnic resistant groups, govern more than half of Myanmar’s territory.

The area around Indawgyi Lake is controlled by the SAC, but the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the political wing of the Kachin ethnic group, still maintains some influence in the areas.

Competing groups

“We will not allow any miners to destroy the lake. We arrest illegal miners if we find them,” said U Win Ye Tun, a spokesperson and the Social and Welfare Minister for the Kachin SAC under the junta government.

He added that the SAC had not granted any new licenses to gold miners since it took power in 2021.

“We are working to maintain the good health of Indawgyi lake. We’ve cleared off flotsam to allow water to flow freely and ensure the water flow at the lake’s inlet and outlet.”

However, local residents allege the SAC and other armed ethnic groups – the Kachin Independent Army (the military wing of the KIO) and the Shanni Nationality Army – allow illegal mining to thrive in exchange for revenue from tax collected from the miners.

This allegation is denied by all the political groups, including Colonel Naw Bu, a spokesperson for the Kachin Independent Army, who said his group had banned gold mining, especially in areas near local people’s farmlands.

An anonymous businessman who operates a gold mine admitted to a reporter that he ran it illegally and had to pay tax. But he refused to say which group he paid tax to.

“If local farmers are affected by our mining, we deal with them directly,” he said.

Local conservation groups believe the impact of illegal gold mining will worsen water quality and cause flooding – things that have already been aggravated by climate change.

Myanmar was ranked second among countries most suffering from climate-related extreme weather in the past two decades, according to the Global Climate Risk Index 2021 released by the think tank GermanWatch.

The number of floods has increased around Indawgyi Lake in recent years. This year alone, there were three heavy floods that damaged people’s houses and rice fields.

Zawng, an environmentalist based in Kachin state, suggested that strict measures need to be taken as soon as possible to limit the impact of gold mining, not only in the Indawgyi area, but also in the whole of Kachin State.

“Otherwise, the Indawgyi Lake recognized by UNESCO will be left in name only,” he said.

Note: The identities of some local news sources in this story must be undisclosed due to Myanmar’s ongoing political turmoil that creates a hostile atmosphere for dissidents and outspoken local residents.