QUANG BINH, VIETNAM – It was mid-October in 2020 when Tran Thi Hien watched the weather forecast on TV, which warned of heavy and prolonged rains. She was sure another flood was coming to her village in Tan Hoa commune in Vietnam’s central Quang Binh province.

The 40-year-old mother of two quickly moved her family’s essential belongings, as well as rice, water and firewood, to a pontoon house. But when the floods came, it was beyond anything the Quang Binh native had ever experienced.

“The water came in very quickly and flowed like never before,” Hien recalled. Her floating house nearly drifted away that year.

People in Central Vietnam are no strangers to typhoons, storms and floods. Yet as the climate warms and forests disappear, communities on the coast and in the mountains have found that their age-old strategies to cope with floods no longer work against the more intense and unpredictable natural disasters.

Solutions are sparse and imperfect. Meanwhile, come every storm season, 20 million residents fear for their homes and lives.

Central region hit hard

Every year, between August and November, tropical storms form in the Pacific Ocean and head westward toward Central Vietnam, a coastal corridor that stretches 1,900-kilometers. After making landfall, the storms usually weaken to tropical depressions, dumping heavy rain. As the downpours feed the dense river systems that originate in the mountains to the west, floods rush downstream, inundating the plains.

From 2010 to 2015, Vietnam experienced on average seven storms each year. But over the five years that followed, that number jumped to 11, 70% of which made landfall in the Central region.

Flooding has also intensified over the past five years, making it the most damaging natural disaster to hit Central Vietnam, according to Nguyen Ngoc Huy, a climate change expert who has monitored the weather in the country for nearly two decades.

“Global warming is the main reason for the increase in the frequency and intensity of storms hitting Vietnam,” said Huy.

The 2020 disaster in Quang Binh became known as part of a series of the worst floods and landslides in 100 years to hit the Central region, intertwined with 13 tropical storms that made landfall between mid-September and the end of October.

In that historic storm season, 356 people died, thousands lost their homes and the damages totaled VND3.6 trillion (US$153.5 million).

A traumatic experience

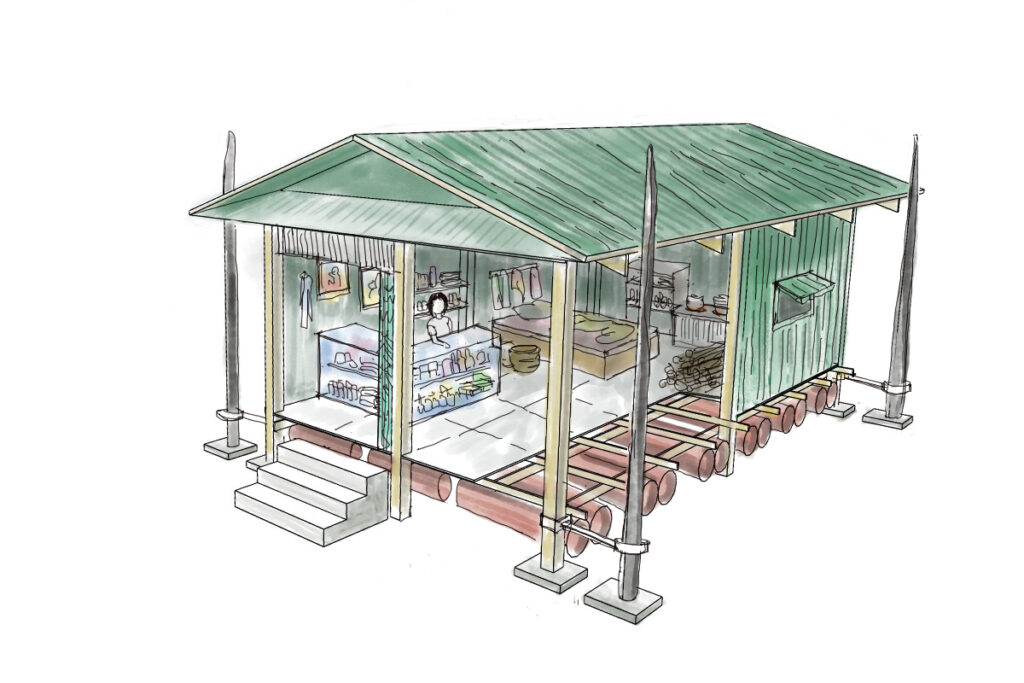

A couple of years ago, following the initiative of a fellow villager, Hien borrowed VND120 million ($5,100) to build a pontoon house. The design is simple – a structure with corrugated iron walls and roof and wooden plank floors, all supported by empty plastic drums.

As the water level rises, the house floats like a buoy, but does not drift away as it is anchored to at least two wooden pillars.

These pontoon houses have helped the people of Tan Hoa survive multiple rainy seasons. However, the 2020 floods were different, as witnessed by a Mekong Eye contributor who was there.

On the first night of the flood, the water level rose rapidly and covered the wooden pillars, several Tan Hoa residents told Mekong Eye. Locals had to stay up all night monitoring the water level and lengthening the pillars. Eventually, many ran out of the timber needed to extend the pillars as the water level continued rising.

In the dark they had no choice but to get into boats and row against the current to tie their pontoon houses to trees, electricity poles or other floating houses.

“The pillars were extended above the flood peak of 2010. I thought the flood level that year, at 6-7 meters, would be the highest ever,” said Hien. “Who knew, in 2020 it was even higher.”

Quang Binh is known as the “belly button of floods” in Central Vietnam – a term used to describe its low-lying terrain which makes it vulnerable to flooding every rainy season. The pontoon houses are only one of the various measures that have emerged.

Many households, for instance, have also opted to build two-story concrete houses with the 2010 flood level used as a reference for the ground floor ceiling. When hearing about an incoming flood, families in these houses move their belongings upstairs.

But in 2020, historical references proved futile. The water rose so high that people had to stack up tables and chairs to stay dry, interviews with local residents and authorities indicated.

For poor families with only one-story houses, that year’s floods turned their shelters into a trap. From the mezzanine designed to keep the inhabitants and food dry, people removed tiles to climb out onto their roofs.

Thousands of households in Quang Binh sent calls for help via phone and Facebook in the dead of night from their submerged homes. Heavy rain, strong winds and currents made it impossible for rescue boats to quickly reach those in need.

In Tan Hoa, Hien and her children were dry in their pontoon house. But Quang Binh was covered in water for more than a week, longer than she had expected. And like many other households at the time, they faced hunger.

“I thought it would be flooded for two to three days as usual, so I only reserved that much stuff,” she said. When the food and fuel dwindled, they had to collect rainwater to drink while rationing what few instant noodle packs they had left. A rescue team only reached them after one week.

Forests in decline

At the end of 2020, the government acknowledged that the “loss of forests and low quality of forests” had played a role in the magnitude of the floods.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, in the six years between 2012 and 2017, 38,000 hectares of forest were lost due to economic development projects. But in the four years between 2017 and 2020 alone, this number nearly doubled, up to 60,000 hectares.

Global Forest Watch data show that the Central region is the most deforested area in the country. Most of the forests have been flattened for timber, tourism, transport infrastructure and hydropower.

“In the past, the mountains and forests were rich there,” said Ngo Van Hong, a forestry expert at the Center for Indigenous Knowledge Research. “Now it’s a barren hill, or zones of acacia – a species of tree with only economic value but not the ability to keep the land stable.”

Looking for a needle in a haystack

Vietnam can now reliably predict a storm five days in advance, while warnings of widespread rain can be issued with confidence two to three days prior.

The issue lies with how to deliver the forecast in a way that is easy to understand for local people, said Huy, the climate change expert. That means the weathercaster should lay out specific risks people in relevant provinces are likely to be exposed to because of the incoming downpour.

The increased unpredictability and intensity of natural disasters is also prompting changes to how humanitarian assistance is provided. Instead of offering help after a disaster strikes, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) decided to activate their aid help packages for the people of Central Vietnam before Typhoon Noru made landfall in October last year.

This approach, its proponents argue, saves lives and costs because preventable negative outcomes are avoided, while locals are better prepared.

However, many proposed adaptation solutions remain contentious. For nearly 10 years, the government implemented a program to help poor households in the Central region build concrete houses to avoid storms and floods, but most locals aren’t enthusiastic about this.

According to authorities in Tan Hoa and An Thuy communes in Quang Binh province, people refused to take part in the scheme because the support rate of VND12-16 million ($508-677) was too small and not enough to build even half a house.

“This is too absurd for a flood-prone, basin terrain like Tan Hoa,” said Truong Thanh Duan, Chairman of the Tan Hoa Commune People’s Committee. “It shows. Two-story houses were also submerged in the flood in 2020. Only the pontoon house can withstand the floods here.”

While the government favors sturdy concrete houses, some charities in the country are supporting initiatives to replace them with pontoon houses. Yet according to locals Mekong Eye spoke to, not every household can apply this model.

“They (pontoon houses) are very light, so can be easily knocked over by windstorms and fast-moving currents,” Thai Xuan Luc, who invented the model, told Mekong Eye. “We’ve never ever coped with floods and storms at the same time. If one day this happens, it will be extremely dangerous.”

Any flood-safe housing solution should be built based on indigenous culture and knowledge, while staying in harmony with the landscape of the area, said Ngo Anh Dao, an independent planning and ecology expert. She argued that the design should not focus exclusively on its flood prevention function.

Floods are temporary, they come and go within a short period of time. Therefore flood-proof structures should be considered as a backup space. This is why she advocates for community flood-proof houses where villagers, livestock and other animals can take shelter.

“But this search for solutions is like looking for a needle in a haystack, it can only help increase people’s resilience so much,” Dao told Mekong Eye. “When mountains and forests are flattened, only God can save us.”

Surviving a disaster does not mean that the danger is over. How to start over while withstanding future rainy seasons is what the people of Central Vietnam have to grapple with constantly.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, it could take many families about 10 years, sometimes never, to get back to how things were before losing a home to floods.

The grocery store, the livelihood of Hien’s family, was damaged in the 2020 floods. By the time the floods receded, farmers in the Central region found they had lost all their rice crops and seeds. Three years on, and they have yet to fully recover.