BANGKOK, THAILAND – Solving transboundary air pollution in Thailand, as well as in the Mekong region, needs improved transparency in food supply chains, with some goods linked to burning agricultural fields that result in a haze that affects people’s health.

Since early this year, the upper and central parts of Thailand have been engulfed in a hazardous haze that has caused widespread illnesses.

Thailand’s Public Health Ministry reported in March that more than 1.73 million people across the country had suffered air pollution-related diseases in the first two months of this year.

More concerning is the fact that almost 200,000 people were hospitalized due to respiratory problems in the first week of March alone.

In Chiang Mai, a touristic city in northern Thailand, more than 12,600 patients sought treatment for respiratory problems at a local hospital between January and March.

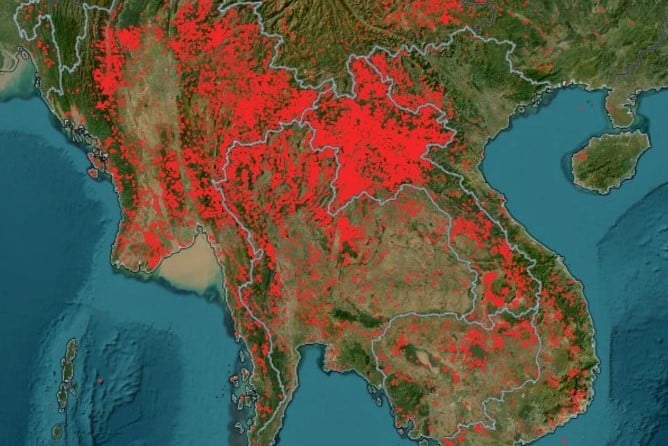

The sources of air pollution are varied, ranging from fossil fuel combustion in vehicles and forest fires to dust from construction sites. However, agricultural burning is seen as the prime culprit as NASA’s satellite images show fire hotspots across the Mekong region – consisting of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.

The hotspot numbers were intense in the northern parts of Laos, Myanmar and Thailand, where farmers burn off agricultural residue, especially in sugarcane and maize plantations, during the harvesting season.

Burning is a common and low-cost practice used for preparing the land for the next cultivation.

Many people have suggested the Thai government provide incentives, including access to low-interest loans and subsidies for purchasing machinery, to discourage farmers from burning off their fields.

But this issue on the ground is far more complex and may not be solved with simple financial incentives. Burning has become the only choice for many impoverished farmers who supply crops to Thailand’s growing food industry.

Without a cash flow and with a lack of market access, many farmers commit to agricultural companies or middlemen collecting and delivering crops for companies. The farmers commit to produce certain amounts of crops through pervasive contract farming.

In exchange, the farmers receive cash in advance or the means of production, including fertilizers, seeds or know-how.

If their production cannot reach the targeted amount, or if crop prices fall by the time they harvest, they may end up owing money to those providing them with the means of production. Therefore, many poor farmers decide to burn agricultural residue to save costs and take a shortcut to the next round of cultivation.

Another factor that drives the agricultural burning practice is the drastic growth in food demand that results in bilateral agreements and regional frameworks that promote economic crop trade in the Mekong region.

One such framework is the Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMEC), and one of its objectives is to promote agricultural cooperation among the five Mekong countries through contract farming.

Adopted in 2003, ACMEC allows the Thai government to import crops from neighboring countries through provincial offices at the borders which are exempt from import tariffs, without going through a complicated process and documentation at the national level.

But that also results in the spread of contract farming, especially in Laos and Myanmar, even after the tariff exemption was revoked in 2009.

In 2013, during the fifth ACMEC meeting in the Lao capital Vientiane, Thailand proposed the promotion of investment in economic crops through contract farming cooperation with ACMEC countries, particularly crops with high domestic demand, such as soybeans and maize.

Thailand, the home of several powerful agribusinesses, and Laos signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on cooperation in the promotion of the Contract Farming Scheme.

The five Mekong countries also adopted the Nay Pyi Taw Declaration of the sixth ACMEC meeting in 2015, with the 2016-2018 action plan that included the encouragement of bilateral and multilateral contract farming as “an efficient mechanism to promote market stability and food security” in ACMEC countries.

Following the promotion of contract farming, a 2012 study by a Thai researcher indicated that Thai food companies invested in 512,000 hectares of maize farming in neighboring countries – 9% in Laos, 16% in Cambodia, 22% in Myanmar and 53% in Vietnam. Very few studies have traced the companies’ investments in recent years.

Maize is the main ingredient for animal food used to feed livestock, which produces meat for human consumption.

The Bureau of Agricultural Economic Research estimated that Thailand needs approximately eight million tons of maize per year. However, it can only produce five million tons and requires imported supplies from neighboring countries.

Vast areas of maize plantations can be found in provinces along the Thai-Myanmar and Thai-Lao borders, including in Myanmar’s Myawaddy in Kayin State and near Huay Xai city in Laos, where imports into Thailand are easy.

Thailand is also keen to expand its own maize production.

Since 2014, the Thai government joined hands with agro conglomerates to promote large-scale maize cultivation through contract farming to provide extra income to rice farmers during the dry season.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives reported in November 2018 that 114,775 farmers participated in the project, covering a total of 160,000 hectares.

Thailand’s Bank for Agriculture and Cooperatives (BAAC) was utilized to provide incentives to farmers by offering them credits at the registration points. Representatives from seed producers also provided training to farmers and promised to buy their crops.

This movement clearly shows that the public-private partnership is used to propel maize production, of which demand will continually grow in the next 10 years based on the Thai Feed Mill Association’s forecast.

However, a study on ACMEC shows that contract farming promotion does not necessarily translate into economic and social development. In many cases, it causes negative impacts on the livelihoods of farmers and the environment.

This impact has been seen in Myanmar’s Shan State.

Bordered by Thailand’s northern region, Shan State has become the most important maize cultivation area in Myanmar, as well as the source of transboundary haze, with a density of hotspots in burning seasons from January to April.

The Myanmar government’s 2021 statistical report pointed out that 56% of Myanmar’s maize plantation areas, or nearly 290,000 hectares, were in Shan state.

Many of these plantation are the result of massive land clearances, where farmers transform lush forest into barren hills for maize cultivation. They also lack access to infrastructure, irrigation systems and technology to improve productivity and must stick with cheap methods, such as burning.

Another study conducted by the Bureau of Agricultural Economic Research pointed out that Myanmar produced nearly three million tons of maize per year, but only one of those three tons is used in the country. The rest is exported to other countries, including Thailand and China. A similar market trend is seen in Laos and Cambodia.

With the complex nature of transboundary haze, solving it will need multiple measures, even institutional changes, including the reinvention of the Thai food industry to emphasize transparency throughout supply chains.

There is also the need for holistic approaches to improve farmers’ livelihoods and technology adoption, as well as strong collaborations among the five Mekong countries to ensure sustainability in agricultural cooperation.

This analysis was first published on Sarakadee Magazine. Mekong Eye translated it and added more information to clarify some points while offering context to readers.