KRATIE, CAMBODIA – Impoverished indigenous people on a large island in the Mekong River are looking at ecotourism as a way out of poverty – and a way to get their children an education.

With many of the island’s children dropping out of school because of poverty caused by environmental degradation, some local villagers have been busy setting up ecotourism tours in their area in the hope of providing more opportunities to the young generation.

On one recent breezy morning, 14-year-old Koy sat on the bow of a tourist boat as it cruised along the Mekong River near his hometown on Koh Samseb, a large island with a community-based ecotourism site in Kratie province, in northeastern Cambodia.

As an amateur tour guide, the ethnic Bunong teenager can earn up to 20,000 riels (about US$5) on a good day. He often spends some of his earnings treating other children in his village to energy drinks and sodas.

While Koy was enthusiastic about his work, what’s notably missing from his life is a consistent school schedule. When asked why he doesn’t go to school, Koy shrugged it off.

“Sometimes during the year, I go to school, and sometimes I don’t. I like working like this more,” he said.

Koy was not the only child missing school on Koh Samseb, which is home to many indigenous communities, including hundreds of Bunong and Kuy families.

Their lives revolve around the Mekong River from dawn to dusk. At least 90% of the communities make a living from fishing. Many also rely on forest products to further their incomes.

With multiple environmental challenges – from climate change and hydropower dams to illegal logging and fishing – the indigenous people cannot fully depend on the river and forest anymore, and are likely to be pushed deeper into poverty.

This has a knock-on effect and means many children will drop out of school because their parents cannot afford to pay for their education, or they must work to feed their families, like Koy.

Indigenous children in Cambodia already face extra hurdles in accessing basic education, which has been further exacerbated by school closures and economic challenges brought by the pandemic.

The community’s development and infrastructure also plays a part. Koh Samseb’s nearest high school is more than 40 kilometers away, and there is no public transport. Commuting to school is a luxury most children cannot afford.

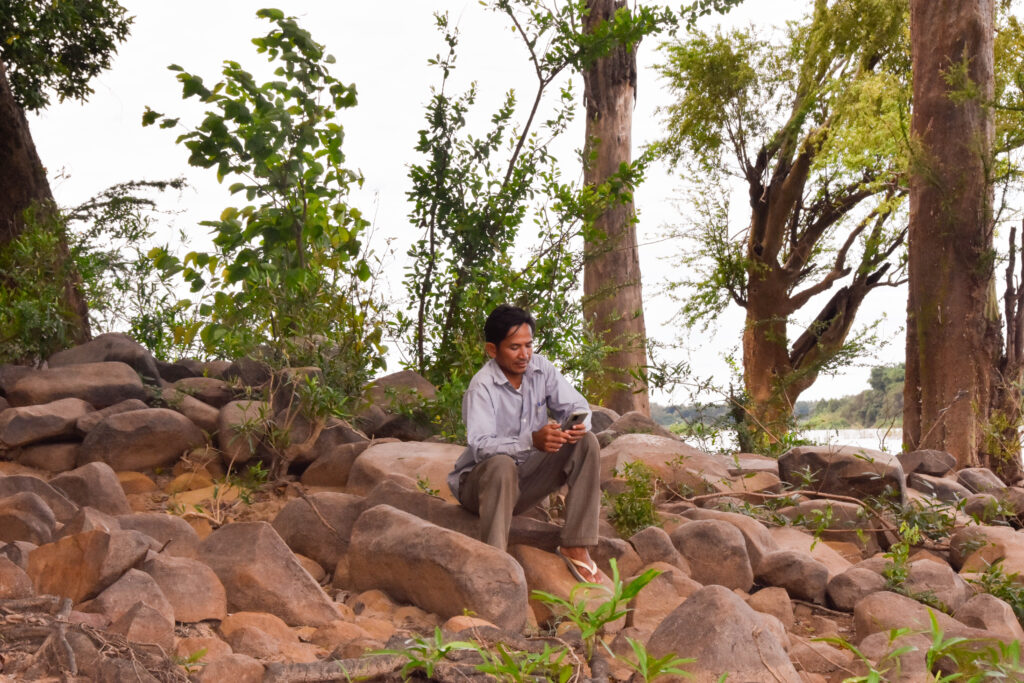

“There are very few kids who make it past secondary school in this village, probably even less than 2%,” said Khut Sam Ol, 37, an ethnic Kuy and the community leader of Koh Samseb’s ecotourism business.

Languishing in poverty

About 80 million of the 200 million people in the Mekong region are classified as poor and in remote areas. Some of the poorest communities are made up of indigenous people whose livelihoods depend on natural resources.

“Tens of millions of people rely on the Mekong’s natural resources, mostly for fishing and agricultural production. But the Mekong’s bounty is threatened to be wiped out by upstream dams, poor land use choices, poor regulation of extractive practices like fishing and sand mining, and climate uncertainty,” said Brian Eyler, the director of the Stimson Center Southeast Asia Program.

“Key livelihood practices for people living near the flooded forest are particularly at risk from these impacts. If their fishing bounty is wiped out, their villages will empty out and people there will likely move to larger urbanized areas looking for jobs. Others will languish in poverty.”

This rising poverty also affects the level of safety and trust among community members.

Sam Ol comes from Koh Samseb and is the father of two teenage daughters, who he had to pull out of school because commuting was no longer safe. He has asked the authorities more than once to build a high school in his village, but has never had any replies.

“When students drop out of school, some of them turn to drugs or illegal activities,” he said. “It is very bad for their future, and it causes great harm to the village’s stability.”

Sam Ol noticed that more children have dropped out of school as the years pass by. Some of them, especially the boys, are likely turn to black economies such as illegal logging and fishing, which eventually creates a vicious cycle of poverty for the many communities relying on natural resources.

A UNESCO report published in 2022 pointed out that even though girls generally encounter more challenges in accessing quality education and make up the majority of out-of-school children at the primary level, boys tend to face more challenges at later stages of education.

Poverty and the need to work are important drivers behind school dropouts. In some contexts, society expects boys to be future breadwinners, which makes them feel pressured or demotivated to pursue an education.

It’s not all smooth sailing

Sam Ol used to poach wildlife for a living until he left his hometown in 2004. He decided to turn over a new leaf when he returned five years ago and is now dedicated to transforming Koh Samseb into an eco-tourism spot.

“The idea is that we can create more jobs for the locals here and we can protect the natural resources too,” Sam Ol said, adding that the economic benefits from tourism would allow children to have better access to quality education and infrastructure.

The potential of Koh Samseb as an ecotourism destination is hard to ignore.

The village is in a prime spot in the Sambo Wildlife Sanctuary, which is a paradise for river birds with more than 218 documented species, including 50 wetland species and many endangered birds. The area is also blessed with a wide water basin adorned with white sandy beaches, uninhabited by people.

This creates a greater remote value for higher-end tourists, who are willing to pay for the privilege of staying in aesthetically attractive and undisturbed landscapes in protected areas.

But the journey towards this transformation has not been smooth sailing.

Sam Ol and his team have faced resistance from many indigenous people who are skeptical about eco-tourism, preferring instead to stick to their traditional livelihoods of fishing and forest products.

The high illiteracy rates among local community members are also a challenge. Because they can’t read, they can’t fully absorb new knowledge offered in training related to tourism businesses. Only 16 of more than 200 families in the village are involved with ecotourism.

The inconsistency of tourists is another factor that makes locals hesitant about getting involved in the ecotourism industry. It becomes even more challenging as Koh Samseb must compete with more popular destinations in the country, as well as overseas travel.

“While there is a lot of potential to explore Cambodian ecotourism, it can’t yet serve as the primary source of income for the people’s livelihoods,” said Srey Moch, a lecturer on sustainable tourism at the Kingdom’s largest university.

“Another way to look at it is how can we support the people through small- or medium-sized businesses which would stabilize their economy better. Then, ecotourism can come in as their additional source of income.”

Man-made potential

The tourism industry is a key contributor in Cambodia’s economic growth, with Angkor Wat the landmark destination.

A 2020 World Bank report suggested that a recent tourism slowdown, along with the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, indicated a need for diversifying tourism products, including further development of nature-based ecotourism to create jobs and provide stimulation for livelihood building within rural economies.

Thida, a 42-year-old immigrant, is one local who sees the potential of Koh Samseb, despite it being in a remote area.

She settled in the village with her husband five years ago to do riverbank farming, leaving her four children with her parents in Kampong Cham province so they could attend regular schools and have a normal life.

She became the only woman involved in the community’s ecotourism business, taking care of cooking and managing the only homestay on Koh Samseb.

“If the season is good, I can earn a decent amount of extra income for the family. However, we can only run [our homestay] for one season a year [a dry season spanning from November to January]. I can’t totally depend on it yet,” she said. “We still have a lot of work to do [to establish ecotourism here.]”

But Thida, as well as Sam Ol, remain hopeful that they can push forward with ecotourism so the village will thrive.

“We know that we cannot depend on the Mekong River forever,” Sam Ol said. “This natural resource is not going to be there all the time. We have to develop man-made potential too.”

This story was supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network under the grant for reporting on water governance from gender and social inclusion lens.