Illegal sand mining has been an ongoing issue in Thailand’s section of the Mekong River due to fragmented governance and “influential people.”

NAKHON PHANOM AND BUENG KAN, THAILAND – Crowds of locals and tourists are drawn to Had Hae – a sandy beach that emerges when the level of the Mekong River falls in That Phanom district in Thailand’s northeast Nakhon Phanom province, which borders Laos.

The beach, which looks like an island in the middle of the river, is filled with visitors and local people’s makeshift stalls selling food and other goods during the summer.

Banana boats, swimming rings and jet skis are also available for rent.

This is not only a patch of sand for tourists and residents, but a medium of pleasure and a source of income in the landlocked northeastern region of Thailand.

“The beach is an important part of our community. Local people will set up temporary shops and festival grounds on the beach to celebrate the Songkran Festival (Thai New Year), which happens every summer,” said Phisaksan Senorit, the Deputy Mayor of Nam Kam municipality, which oversees the area.

However, in the past few years, residents have noticed that Had Hae has shrunk, and they fear it will soon disappear, along with the festive culture developed around the sand and water.

Had Hae is formed by a load of sediment carried by the Mekong River, which runs nearly 5,000-kilometers from China’s Tibetan Plateau to the Mekong Delta in Vietnam.

It is submerged during the rainy season and fills with sediments, then reappears in the summer – a natural cycle of sediment flows that creates and maintains islands and sandy beaches in the river, as well as sustaining the cultural activities of local communities.

But this cycle has been changing in the past decade due to rapid development in the upper and lower Mekong River basin.

Sand is mined from the river to feed the construction and industrial boom in the lower Mekong countries of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, as well as serving regional markets.

According to the Mekong River Commission’s

2018 report, sand mining is one of the major

culprits that contribute to sediment loss in

the downstream river, along with hydropower dams.

The sand mining sector is believed to be worth

US$175 million annually.

Sand barges gather near a sand mining site on the bank of the Mekong River in Laos’ Vientiane prefecture opposite Thailand’s northeastern border. The large volume of sand mined in Laos is exported to Thailand. PHOTO: Visarut Sankham

“This is a very serious problem for our community. The excessive exploitation of sand leads to the erosion of Had Hae and endangers our important communal area and tourist attraction,” said Phisaksan.

And his community is not alone.

– SAND THIEVES –

Sand is a vital raw material for construction and industry. The UNEP’s report released in April estimated that the global demand for sand had tripled in the past two decades. However, this estimation is now considered outdated due to increasing economic activities over the past decade.

More than 50 billion tons of sand are extracted from nature globally each year, making it the world’s second most exploited resource.

Nearly 50 million tons of sand are mined in the lower Mekong Basin each year, according to a comprehensive study commissioned by the WWF in 2011.

Thailand alone extracted about 5.8 million tons, Laos 1.4 million tons, Vietnam 12.4 million tons and Cambodia a whopping 30 million tons.

Released in 2021, a study by UK and Cambodian researchers suggested that sand extraction in the Mekong River in Cambodia was 59 million tons in 2020, greater than previous estimates for the entire Mekong Basin.

Due to the limited availability of official data, it is difficult to know the exact amount of sand Thailand extracts from the Mekong River annually.

But some studies point out that the country’s demand for sand has increased drastically in the last decade, with the implication that sand extraction should follow the same trend.

A study on sand demand by the Indian Institute of Technology Madras found that Thailand consumed 85.8 million tons of sand in 2016 due to an increase in GDP from construction and urbanization. The volume surpassed the sustainable threshold of 76 million tons, or the maximum amount of sand a country can dredge without affecting the environment.

Even though the construction sector has slowed since the Covid-19 outbreak in early 2020, sand dredging is still going on.

The dataset obtained from Thailand’s Department of Industry showed that more than 1,200 authorized sand mines operated in rivers throughout the country at the end of 2021. About 140 of those are in provinces bordered by the Mekong River.

Dredgers are often seen in the Mekong River, sucking up sand from near the riverbank close to Had Hae, where local people enjoy their leisure time in That Phanom district.

Many of these vessels are registered in Laos, but they cross the river to illegally mine sand in Thai territory. The sand is then carried back to the Lao side and tagged as a commodity of Laos.

A local official said anonymously that 80% of this sand is exported back to Thailand, while the rest is used in Laos.

Some of the dredgers are owned and operated by Thai businessmen who register their businesses in Laos – to avoid tax and Thailand’s zoning regulations that prohibit sand mining in certain areas. These Thai companies also gain access to sand mining concessions in Laos.

Because of these questionable operations, it is impossible for Thai authorities to regulate and tax sand miners, even though they take sand from within Thailand.

Local communities have alerted officials and government agencies for many years, but not much has been done to deter the wrongdoers.

“Whenever the officers show up to inspect the sand mining areas when we file complaints, the dredgers always vanish, as if they knew the officers were coming. The dredgers then reappear and continue their businesses after the officers leave,” said deputy mayor Phisaksan.

Crossing the border for sand theft is only one of many ways to extract sand illegally. There are also other tricks used by sand miners.

– Influential people –

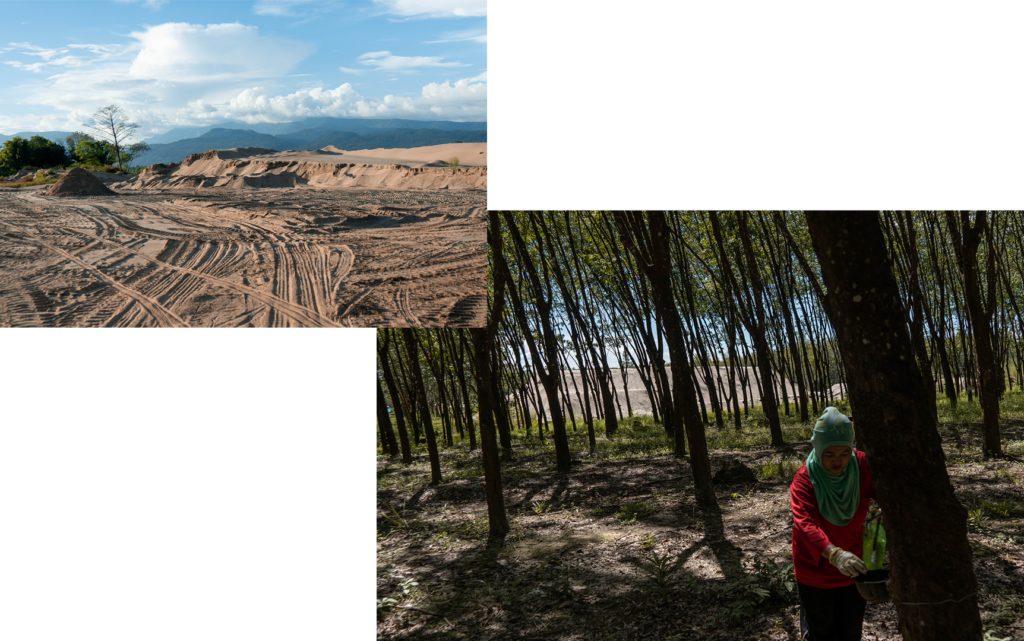

At Ban Huai Dokmai village in Thailand’s northeastern region bordering the Mekong River, illegal sand dredging is done with loose law enforcement because of “influential people” in the mining business.

To operate a sand mining business there, the local authority set a rule that mandates the mining companies consult with local community members and get their support before applying for or renewing their mining licenses.

“In reality, the community is voiceless on this matter. The mining business owners are often influential and powerful people in our areas, so we dare not vote against them,” said Narin Phatili, the village headman of Ban Huai Dokmai.

“If it was truly up to us, we would not vote to allow more sand mining businesses in our village.”

To relieve tensions with the local community, each sand mining operator voluntarily provides 50,000-baht compensation (around US$ 1,600) to the village every year. But the impact from mining – from dust and road damage by sand transported on trucks to erosions of the riverbank – could outweigh that sum of money.

As the mining businesses have a bigger say, the number of sand mines in Khok Kong district has increased from four in 2016 to 24 as of 2022, covering an area of about 26 hectares.

This makes it one of Thailand’s biggest sand mine clusters on the Mekong River, according to the dataset obtained from the Department of Industrial Works.

A source working in a local authority office revealed that at least two unlicensed sand mines had been operating in the district. They were owned by local mafias linked to local politicians and somehow managed to evade law enforcement.

Some licensed miners are also reported to be involved in illegal sand mining to increase their output and avoid tax. They mine sand in and outside the concession areas, then falsely declare the volume of sand production to be lower than the actual yield.

Suttipong Juljarern, the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of the Interior overseeing sand mining permission, said that sand theft is a sensitive issue and could affect relations with Laos.

But the Thai government does not ignore the problem, he said. The provincial governor and local authorities have been consulted and collaborated with authorities in Laos to find mutual solutions.

– From erosion to land loss –

Released in 2018, WWF’s research highlighted the many physical impacts of sand mining, from river bank erosion and land loss to alternation of habitats and water quality.

Sand mining in the lower Mekong may also be associated with the changing hydraulic balance between the mainstem Mekong and its subsidiaries, including the water flow in Cambodia’s Tonle Sap. It can also affect the extent and duration of saltwater intrusion in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta.

These impacts are being exacerbated due to hydropower development, which traps the sediment load of the Mekong River, suggested the research.

In Thailand, the clear physical impact includes erosion, with Thai authorities spending millions of baht each year building embankments long the river.

The Office of National Water Resources

surveyed riverbank erosion in eight

provinces bordered by the Mekong River,

and found between 18 to 24 square kilometers

of erosion areas from 2018-2020.

The areas reduce from the previous surveys in

the period of 2014-2018 (46 square kilometers)

and 2012-2013 (44 square kilometers) because

of increasing embankment construction.

Along Thailand’s northeastern border on the Mekong River, concrete embankments are being built to prevent severe riverbank erosion. PHOTO: Visarut Sankham

The UNEP warned in its report that the world was now facing a sand crisis, as the global resource of industrial sand was quickly dwindling due to excessive sand extraction, especially from rivers.

“Unlike ocean sand and desert sand, sand from rivers and inland sources has the size and shape that is ideal for construction work,” said Assistant Professor Kiatsuda Somna, a lecturer at the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture of Rajamangala University of Technology Isan.

“River sand is considered a critical commodity for the construction industry. We use this type of sand as a main component in construction from homes and roads to infrastructure projects. We are heavily reliant on the limited sand resources from rivers.”

– Fragmented governance –

Thailand has enforced the law to regulate river sand mining, while adopting regional and bilateral agreements on sediment management.

But enforcement is not effective due to the fragmented governance that involves a multi-level of actors. None take the lead in looking at the impact of sand mining in the big picture.

At the national level, river sand mining is regulated by the Ministry of Interior overseeing provincial and local administrative bodies.

A sand mining operator seeking or extending permission must submit a set of documents to a provincial sub-committee for scrutiny, chaired by the governor. If approved, the subcommittee will report to the national committee on sand mining, chaired by the permanent secretary of the Interior Ministry, who gives the final approval.

The permission relies on the decision at a provincial level, which may not consider a bigger picture of the scale and impact of sand mining along the Mekong River, and lead to an over-exploitation of sand.

On the other hand, river sand mining does not require an Environmental Impact Assessment, despite its significant impact on the river’s ecology and local livelihoods.

Although the Ministry of Interior requires mining operators to consult local communities before requesting a license, the consultation process may not be meaningful. Mining operators are powerful people in many cases, forcing local communities into silence.

On a regional level, the Mekong River Commission (MRC) was established in 1995 by the governments of Mekong countries to ensure “reasonable and equitable use” of the Mekong River through a participatory process of consultation and discussions.

In what is seen by many as a major failure, sand business management has not been highlighted by the MRC.

However, the MRC Secretariat is conducting a study on sediment transport and erosion, which will suggest potential interventions to reduce sediment retention and improve sand mining practices. This study is scheduled to be completed in 2023.

– Adverse impact –

of strict regulation

Meanwhile, Thailand and Laos have co-established a Joint Committee for Management on the Mekong River and Heung River (JCMH) to regulate natural resource extraction in both rivers, including sand mining, in the territories of the two countries.

For sand mining businesses, the JCMH, which imposed restrictions on mining zones six years ago, is seen as the main driver for illegal mining in the Mekong River.

Monnipa Kovitsirikul, chairwoman of the Thai Chamber of Commerce in Nong Khai province which is bordered by the Mekong River, explained that the JCMH prohibits sand mining within a 1,000-meter radius of permanent structures – including bridges, piers and river embankments.

As embankments were constructed over large parts of the riverbank, the permitted areas of sand mining shrank. More than 40 sand miners had to close their businesses. The rest relocated to the few areas that were still free of embankments.

The strict regulation resulted in an adverse impact, where sand mining operators sought dodgy solutions to ensure the survival of their business – including mining in prohibited zones.

Thailand and Laos have agreed that the rule is too strong. But they are still unable to ratify the new agreement.

To relieve the tension, Thailand’s national committee on sand mining had a resolution to allow provincial administrations to revise mining zone bases in the local context of the environment and economy.

Suttipong, the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Interior and the chairman of the national committee for sand mining, acknowledged that illegal sand mining was an ongoing problem.

People mining illegally can face five-years imprisonment and a 20,000-baht fine, according to article 9 of Thailand’s Land Code Act.

– Substitute sand –

As the shortage of sand can lead to disruptions to infrastructure development and industry, the UNEP has urged the international community to follow a resolution on mineral resource governance adopted at the fourth United Nations Environment Assembly in March 2022.

The solution included the use of recycled materials which can substitute for sand.

At present, many researchers and academic institutes in Thailand are developing sand substitute products. Those include Rajamangala University of Technology, which is focused on developing construction materials from marine plastic waste.

“River sand is a main ingredient, along with gravel and crushed stone, used for mixing concrete to strengthen the building structure. For the typical concrete mixture for regular building construction, these aggregates are made up of about 70% of the component,” said Assistant Professor Kiatsuda from Rajamangala University of Technology Isan.

“If we can find alternative materials that share similar consistency and characteristics with sand, we can theoretically use it as a sand substitute in construction and reduce the need of natural sand supply in the construction sector.”

Assistant Professor Prachoom Khamput, the head researcher in the marine plastic waste project, explained that his team shredded plastic waste and used it as an additive component in construction products, such as floor tiles or concrete slabs.

His team launched trials at two communities in Chonburi’s Sattahip district and Samut Prakan’s Phra Samut Chedi district. They succeeded in setting up the upcycling facility while cleaning the ocean and generating extra income for local communities selling alternative building products made from marine plastic waste.

However, Assistant Professor Prachoom admitted that the production costs of upcycled plastic waste was still much more expensive than river sand extraction. The cost mainly comes from the process of shredding the plastic, which must ensure consistency and quality to make strong building materials.

“Sand substitute material from plastic waste is not ready to compete with sand. We are still using it in small and localized-scale construction. But I think it can potentially be adoptable on a commercial scale in future,” he said.

This story is part of the “A Thirst for Sand” series, which was produced in partnership with the Environmental Reporting Collective. This partnership brings in journalists from 12 countries to expose how a weakly regulated industry overlooks the environmental destruction and human toll of the highly lucrative and low-risk business of sand mining.

Data visualization is provided by Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Environmental Reporting Collective. A map used in this story is sourced from Mapbox.

Explore more stories: