Story and Photography by Yostorn Triyos

MAE HONG SON, THAILAND – In winter, international tourists flowed into Thailand’s northern towns when the country fully opened its borders after the Covid-19 pandemic.

The sleepy town of Mae Sariang in Mae Hong Son province near the Thai-Myanmar border was full of visitors. Hotels and guesthouses were fully booked, highlighting the end of a pandemic that killed more than 30,000 people in the country.

However, a one-hour drive from the town is Mae Sam Laep village, where silence and fear chill the air.

While the whole country celebrated a return to normal life, residents in this small Thai village – many of whom fled from war-torn Myanmar – are haunted by the decades of civil war happening right on their doorsteps.

Mae Sam Laep is next to the Salween River, the last free-flowing river in the Mekong region. Less than half a kilometer of this more than 3,000-km-long river is the border that divides the two countries.

The sound of gunshots and explosions has become part of the villagers’ daily lives, along with the occasional sound of military aircraft from the Myanmar side of the river.

Facing Myanmar’s Karen state, the villagers in Mae Sam Laep have seen the fighting between Myanmar’s military, known as the Tatmadaw, and the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), escalate after the military coup in February 2021 – which overthrew the elected civilian government and left the country into turmoil.

The KNLA is the armed wing of the Karen National Union (KNU), a political organization that has fought Myanmar’s central government since 1949 and called for a federal state in which ethnic Karen can determine their own political direction.

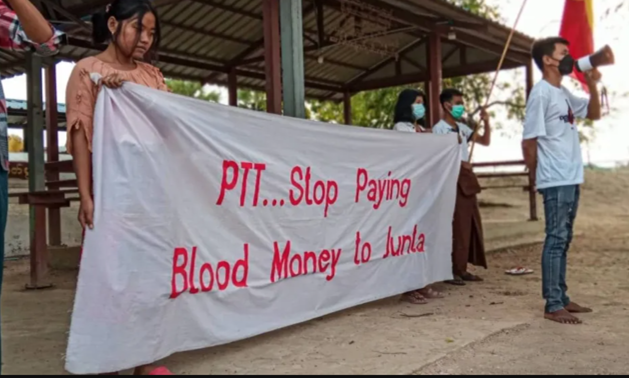

The coup resulted in a rapidly growing resistance to the Tatmadaw by armed groups across the country, and the KNU was no exception. The military’s response was to deploy more forces and launch a series of airstrikes and raids aimed at cracking down on the resistant groups.

At least 23 airstrikes were reported in Dooplaya district in southern Karen state from December 2021 to May 2022, according to the Karen Human Rights Group’s report.

This resulted in several thousand Karen people fleeing across the Salween River to Mae Sam Laep in Thailand – creating a humanitarian crisis that halted the local economy and the tourism industry.

Bunkering down

As clashes between the military and armed groups increased, villagers along the Thai border were forced to build safety bunkers to avoid stray bullets from the Myanmar side. Students in Thai schools had to undergo evacuation training to prepare for unexpected fighting nearby.

The escalating violence also disrupted the transportation of food and necessities on the Salween River.

When I visited Mae Sam Laep early this year, the ports were empty and lifeless despite the lifting of Covid travel restrictions. Only a few boats were seen carrying goods from the Thai to the Myanmar side.

Thai authorities had set up areas to temporarily host displaced people from Karen State. The border was officially closed due to security concerns, while visitors were not allowed to get near the border.

This ghostly atmosphere contrasted with the pre-coup period when boats would queue up at the ports, waiting for passengers and goods to be carried over to the Myanmar side. Local villagers would organize boat trips for tourists, who came to explore the lush and then peaceful scenery along the Salween.

Restaurants were crowded with customers looking to try local food.

After the coup, many villagers reported seeing the Myanmar military’s fighter jets flying over their towns. However, this was denied by Thai security officers, who said the jets had not entered Thai air space.

“We are mostly afraid of airstrikes,” one villager told me. “Many of us used our mobile phone cameras to capture photos of Myanmar aircraft flying near our houses. But we were asked by [Thai] soldiers to not upload the videos on social media or send them to journalists because it would affect diplomatic relations between Thailand and Myanmar.”

With the villagers urged to stay silent, their stories have not been heard by outsiders, making the ongoing war invisible to the outside world.

But this silence is louder than any sound. It resonates with the difficulties of villagers whose lives will not be at peace anytime soon.

Rebuilding the economy

However, living in the shadow of war, some villagers feel they cannot let themselves and their people be forgotten by outsiders.

Recently, a group of villagers joined hands with local politicians in an effort to restore eco-tourism, with an attempt to bring in tourists despite the ongoing war on the other side of the border.

Led by Phongphiphat Mibenchamat, the head of the Mae Sam Laep Administrative Organization who is known locally by his nickname Chai, the villagers hosted a media boat trip to show the natural beauty of the Salween River and the forest surrounding it.

They hope the media will spread the word about their village and its attractions. Tourism can play a crucial role in boosting the local economy in the post-pandemic era as cross-border trade and farming have been disrupted by the war.

“Tourist safety is still a challenge. But we must start rebuilding our profile in the industry now,” said Phongphiphat.

Meanwhile, both the war and the pandemic have created a political vacuum that halted the development of seven proposed dams on the Salween River. One of those is the Hatgyi Dam, which is only 47 kilometers north of Mae Sam Laep.

It was first proposed by the Myanmar government in 1998 and made a leap forward in 2005 when Myanmar and the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand signed a Memorandum of Understanding to develop the dam.

About 90% of the 1,360-megawatts of electricity generated from the dam will likely be imported to Thailand. But progress has been marred by bloody conflicts and the project is unlikely to move on under the current military government.

This political vacuum may leave civil society groups protesting against the dam in limbo for a while. But they believe the project will be revived once Myanmar’s political situation stabilizes.

Their main concerns are the impact of the dam on the river’s rich biodiversity and people’s livelihoods. Thousands of villagers will be displaced by the dam’s construction.

For local people, the dam seems to be a small concern in the face of never-ending war. Seeking new sources of income, like tourism, while ensuring safety and food on their plates, are now their urgent issues.

However, the gunshots are still ringing loud in their ears.

This photo story was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

Yostorn Triyos is a Thai documentary photographer and a co-founder of Realframe, a group of photographers covering socio-political and human rights issues in Thailand. Find Yostorn’s work at www.realframe.co