PHANG NGA, THAILAND – Early one morning in May, Kitichate Sridith, a botanist from the Faculty of Science at Prince of Songkhla University, set foot in the little-known tropical sand dune forest in Khao Lampi-Hat Thai Mueang National Park in Thailand’s southern Phang Nga province.

His walking trail started from the glaring white-sand beach on the uninterrupted shoreline facing the Andaman Sea.

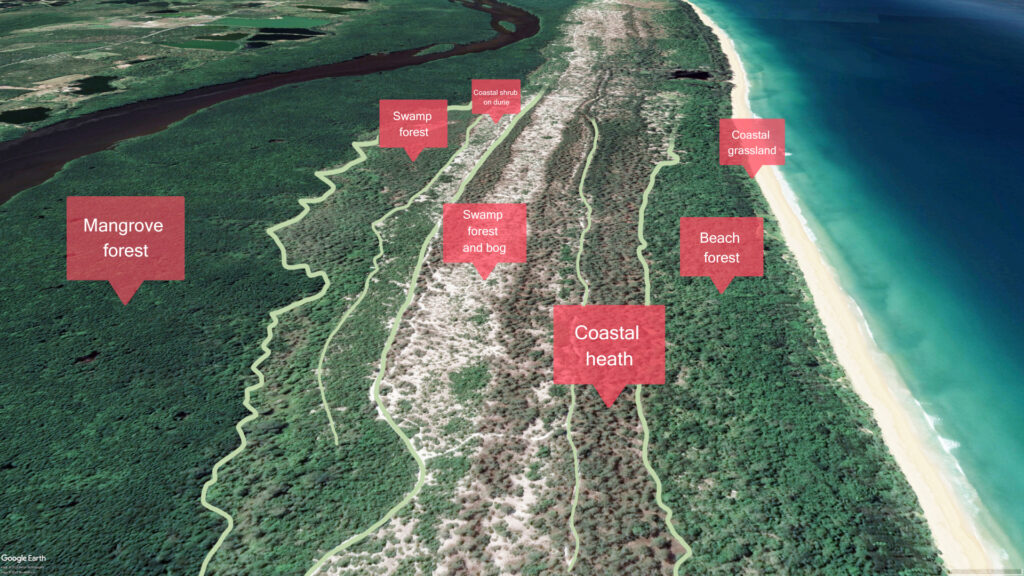

He then went deeper inland, passing multi-layers of forests – from grassland to beach forest, coastal heath, a bog, a swamp and mangrove forest. All create ribbons resembling a multi-colored flag from a bird’s eye view.

Growing on the sand dunes and formed over thousands of years, every layer of this forest comprises plant communities that create a unique ecosystem once commonly found along Thailand’s southern coastline.

“Hat Thai Mueang is home to the last remaining tropical sand dune forest in Thailand and is the least disturbed by humans,” said Kitichate, while walking through the forest and observing the various plant species.

For decades, he has studied sand dune forests and found they have almost all disappeared, except in Hat Thai Mueang.

The major causes include tin mining, which was expansive in southern Thailand 30 years ago, coupled with rapid urbanization and extensive coastal tourism.

The sand dune forest is also the least studied in botanical classes and is often mistakenly seen as a “degraded forest” due to the dwarf-like characteristics of the plants, leading to a lack of conservation efforts.

To preserve this last patch of sand dune forest, a group of botanists, including Kitichate, have pushed for the 7,190-hectare Khao Lampi-Hat Thai Mueang National Park to be recognized on the UNESCO world heritage list – and the Thai government has heard their call.

Unique ecosystem

While leading the way into the forest, Kitichate explained how the formation of sand dune forests starts.

The dune occurs when wind deposits sand grains on top of one another and forms a mound, or a ridge. When the top of the first dune collapses, it creates another dune with the help of the wind – repeating the cycle of dune formation.

A variety of plant species that can survive the dryness and harsh wind then develop their communities there in relation to the distance from the sea and locations on the dunes.

The grasslands at the rim of the sand dunes on the seaward side offer a home to creeping plant species, mostly with interconnected root systems, like beach morning glory, sea bean and coastal grass.

Next to it is the beach forest where wind-tolerant shrubs and medium-sized trees grow and act as a windbreaker for plants growing landward. They include the fish poison tree, cycad edentate, tamanu, spider lily and fragrant screw-pine.

Walking further inland one will enter the coastal woodland, where tree species like payom (Shorea roxburghii) and samet shun (Syzygium antisepticum) take root, while relying on plants in the beach forest for protection from the wind.

Behind the woodland is a transition to coastal heath forest – a dwarf plant community that can survive in sandy soil with extremely poor nutrients – and a bog and swamp forest where plants like swamp pitcher plants, sundews and bladderworts grow and survive acidity.

This waterlogged area sits in the lowest points between the dunes, called slack, which becomes the water source for plant communities on the dunes.

“This is a complex ecosystem that raises various plant communities unlike anywhere else,” said Kitichate. “It must be preserved before we lose it forever.”

He describes Hat Thai Mueang as an area where two botanical kingdoms converge and create distinctive aspects of plants and forests.

One of these botanical kingdoms is in the continental Southeast Asian region, which covers the upper part of Thailand and the lower Mekong region. Another is in the Malesian region at the equator, extending from the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, the Philippines and the archipelago of islands stretching from Sumatra to New Guinea.

Plant species found at elevations above 1,000 meters like Malayan Styphelia (Styphelia malayana (Jack) Spreng) can be found in Hat Thai Mueang despite being situated at low altitude. Ficus trees, epiphytes, ferns and ant plants there adapted and survived in the sandy ground and strong winds.

Reforestation fallacy

After the 2004 tsunami hit Thailand’s southern coast, sand dune forests significantly disappeared – not because of the huge waves, but because of the reforestation effort.

Many post-tsunami reforestation projects introduced the fast-growing beach sheoak in coastal areas and wiped out the existing native plant communities.

Sakanan Plathong, a scientist from the Department of Biology at the Prince of Songkla University, said that beach sheoak is an exotic plant introduced in Thailand over a century ago to supply wood for the railway industry.

Its leaves, when they fall on the ground, release allelochemicals that suppress the germination of understory plants. Its roots, when the trees fall down, break the ground and cause coastal erosion, leading to the loss of sand dunes and the habitats of native flora species.

“In contrast, the dunes are intact in areas where native plants like beach naupaka grow,” said Sakanan.

One month after the tsunami, Kitichate and botanist Phonsin Pholphanin, then a lecturer at the Prince of Songkla University, made several trips to study the disaster-affected areas, including to the sand dune forest at Hat Thai Mueang.

They found the original plant communities were able to regrow and thrive. After observing the forests for more than one year, the researchers concluded that the forest was resilient and could recover if no human activities disturbed this recovery process.

On the other hand, the plants in tourist-attraction Maya Beach in Krabi province took longer for their post-tsunami recovery.

The native plant community there was largely damaged by human activities, including the filming of the 2000 movie The Beach – in which the filmmakers were accused of ripping up vegetation on sand dunes and replacing it with coconut trees to give their set a more “tropical” feel.

On Thailand’s western coast from Krabi up to Ranong, the existing plant communities were altered even before the tsunami. Resorts, fisheries and even military camps were built on the sand dune forests and eliminated the unique ecosystems forever.

Push for global recognition

To preserve the last remaining sand dune forests in Thailand, coastal and marine researchers have partnered with authorities and government officials to get the value of Hat Thai Mueang recognized by the global community.

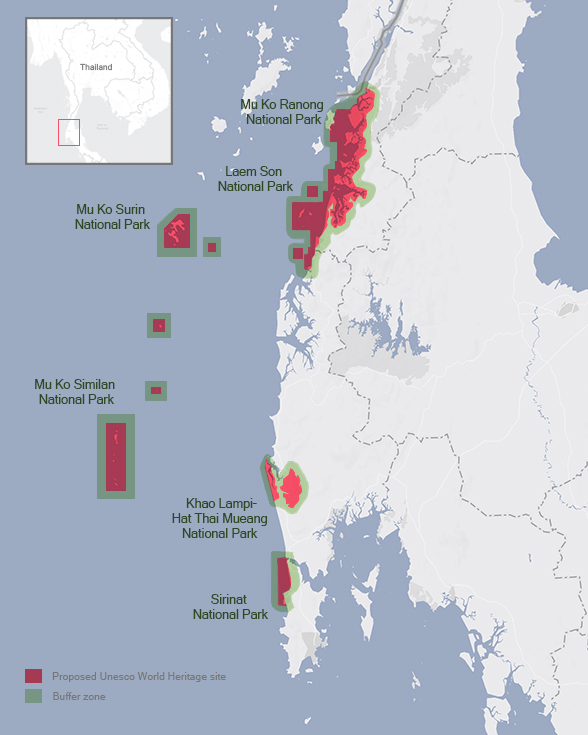

The beach is among six national parks and conservation zones included in the 290,000-hectare Andaman Sea Natural Reserve, which Thailand aims to get included on the UNESCO World Heritage list by 2025.

The sites include protected mangrove forests, Mu Ko Ranong and Laem Son National Park in Ranong, Khao Lampi-Hat Thai Mueang, Mu Ko Surin and Similan in Phang Nga and Sirinat National Park in Phuket.

The Andaman Sea Natural Reserve was added to a tentative list of new UNESCO World Heritage sites in December 2021.

The Thai government is planning to submit its full report to the UNESCO committee after receiving cabinet approval for the bid next year, according to a National News Bureau report.

And although the heat rises at noon, Kitichate kept walking and never stopped appreciating the variety of plant species surrounding him.

“I believe the sand dune forest at Hat Thai Mueang is one of the most outstanding ecosystems on Thailand’s coast. This is where time freezes, where you can find the most authentic coastal forest,” he said.

This is a translation of a sand dune forest story first published in Sarakadee Magazine issue 452, November 2022.