Read the Vietnamese version of the story here. Đọc bài tiếng Việt tại đây.

THUA THIEN HUE, VIET NAM – One morning in 1998, sixth grader Ho Van Ngoc and two friends were fishing in a jungle stream in the forest of Thua Thien Hue province when their dog started barking aggressively.

Grabbing their machetes, the group followed the dog to a rocky ledge, where they spotted a large animal with long, pointy horns.

Ngoc, who had been shown images of this enigmatic creature by forest rangers, immediately recognized it as a Saola, one of the rarest large mammals on Earth which has also been dubbed “the Asian unicorn,” due to its elusiveness.

The three quickly lassoed the shy, non-confrontational animal with a rattan vine and then built a makeshift fence from tree branches around it. They then fed it the stems of the homalomena occulta – a relative of the philodendron – Saolas’ favorite food.

“It folded its head to protect itself from the dog, yet still got bitten on the leg,” Ngọc recalled.

The group then walked 10 kilometers back to Ka Ron village, alerted authorities there to their find, and waited restlessly that night. At dawn the following morning, they set out to see the Saola with forest rangers, who took photographs and eventually released the Saola back into the wild.

In recognition of their extraordinary find, Ngoc and his friends were rewarded with 300,000 VND (US$12) and given a certificate honoring their achievement.

Ngoc’s encounter was the last one recorded between humans and a Saola in the wild. Unbeknownst to science until 1992 and considered one of the greatest zoological discoveries of the 20th century, this large hooved animal now teeters on the brink of extinction.

Today, the Saola Working Group estimates that only about 15-20 individuals are left in the Annamite mountains of Vietnam, one of the world’s only two Saola habitats.

In Vietnam, conservation efforts started in the early 2010s and a decade later, the window to save the world’s last Saolas is narrower than ever. Challenges to conservation, such as illegal hunting, economic development and resource scarcity, are stacking up.

A shrinking population

Ngoc and his friends are among the few people on Earth who have encountered a live Saola. A King, 54, who is also a resident of Ka Ron village, has only seen a Saola after it had been shot dead. The carcass was then butchered and shared among villagers.

“It did not taste as good as other animals, but its horns were very beautiful,” A King recalled.

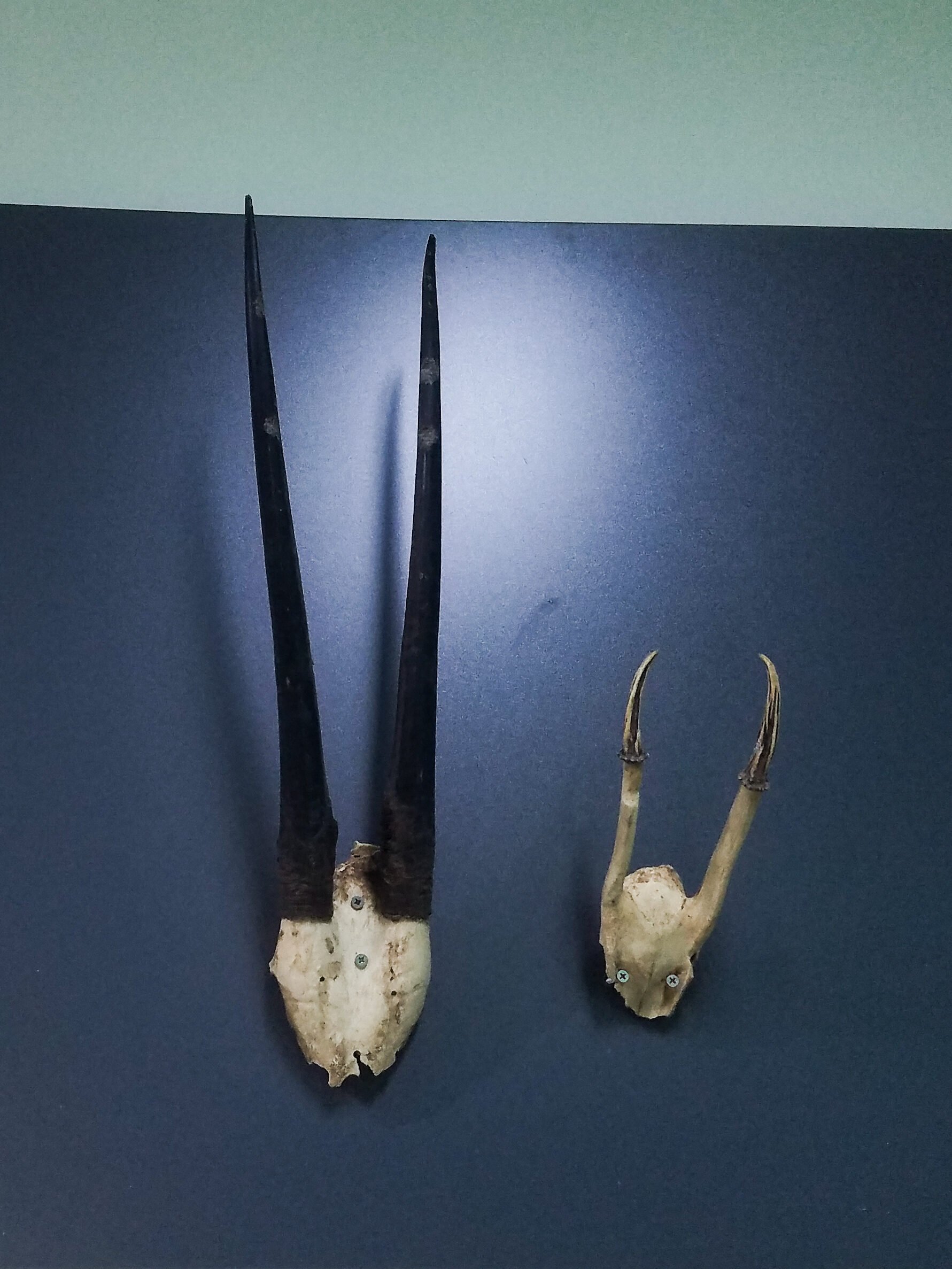

A King has seen his villagers shoot and bring back two carcasses using old AK-47 rifles discarded after the war. A survey by Thua Thien Hue Forest Protection Division in the mountainous A Luoi and Nam Dong districts of Thua Thien Hue also found 27 pairs of Saola horns in locals’ houses.

Hoang Quoc Huy, the Deputy Director of the GreenViet Biodiversity Conservation Center, told Mekong Eye that illegal hunting remained the biggest threat to the Saola’s survival. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), although Saolas are not directly targeted by hunters due to their low trade value, they are still at risk of being trapped and hunted as a bycatch.

Since the opening of the Saola Conservation Area in Thua Thien Hue in 2011, forest patrols have removed more than 22,000 animal traps, mostly wire snares. The Saola Conservation Area in Quang Nam has removed more than 15,000 animal traps and dismantled almost 200 hunting camps between its launch in 2008 and June 2023.

A King recalled that in the 1990s, when the jungle near his village was still teeming with wildlife, wild boars and jungle fowls frequently visited villagers looking for food.

He believes the construction of the Ho Chi Minh Road in the early 2000s gave illegal hunters easier access to the forests and exacerbated the illegal hunting problem.

Other recent economic developments in the region have put more pressure on the already shrinking Saola population.

“The construction of numerous hydropower projects has led to a fragmentation of the Saola range and a disruption of their habitat,” Nguyen Dai Anh Tuan, the Deputy Director of the Thua Thien Hue Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, told Mekong Eye.

“Individuals of the species may exist, but the population size is so small that males and females cannot meet and reproduce,” said Tuan.

Needles in a haystack

Conservationists believe captive breeding is the last hope to protect the critically endangered Saola. The challenge, however, starts with finding live Saolas to breed.

For the past decade, forest patrols in the Saola Conservation Areas in Quang Nam and Thua Thien Hue have regularly placed camera traps in an effort to track Saola activity but have failed to identify any individuals.

Between 2012 and 2014, WWF Vietnam collected leech blood samples in forests where Saola sightings were reported and sent the samples to the Kunming Institute of Zoology in China and the University of Frankfurt in Germany for genetic analysis. According to Le Ngoc Tuan, head of the Thua Thien Hue Forest Protection Division, there was only one sample that could potentially contain a Saola’s DNA.

“It was suspicion at best and there was no certainty,” Tuan told Mekong Eye.

In the few extraordinary cases when Saolas have been found alive, the animal does not do well in captivity. In 1992, Bach Ma National Park rescued a Saola but could not keep it alive due to a lack of knowledge and experience in conserving the species.

In 1996, a Saola named Martha was found in Laos and also died within weeks of being captured, despite being cared for under the supervision of renowned biologist Williams Robinchaud.

The WWF Vietnam estimates that current search efforts have only covered about 6% of the Saola’s habitat. The Quang Nam Saola Conservation Area has 20 camera traps for 15,000 hectares of forest, while the Thua Thien Hue Saola Conservation Area only has about 10 forest rangers who carry out daily patrols, risking their lives traversing the harsh terrain and extreme weather in the Annamite range.

A race against time

Despite the lack of results in the search for the Saola, leech blood analysis helped biologists discover many other important species such as wild boar (Sus scrofa), Serow (Capricornis sumatraensis), the Ferret-Badger (Melogale moschata), Truong Son Muntjac (Muntiacus truongsonensis), Common Muntjac (Muntiacus muntjak), Red-Bellied Squirrel (Dremomys rufigenis) and Macaques (Macaque spp).

“The Saola represents all species under threat,” WWF Vietnam’s Country Director Van Ngoc Thinh told Mekong Eye.

“If we can save the Saola, we can safeguard the forest, biodiversity and their ecological benefits. It is never merely about protecting a critically endangered species,” Thinh stressed.

A new WWF-led project, “Rescue the Saola from the Brink of Extinction,” funded by the European Union, is banking on a new method of searching for the Saola – using water samples, or eDNA.

The project, which lasts from October 2022 to March 2024, is collecting 1,200 samples from 15 water basins in six central provinces spanning across the Annamite range. The project is also involving indigenous people with ecological knowledge to gather information about the elusive Saola.

“We are racing against time to protect the Saola through the captive breeding program with the hope of ultimately reintroducing them into the wild, improving law enforcement to eliminate illegal hunting and wildlife trafficking to restore its habitat,” WWF Vietnam’s Country Director Van Ngoc Thinh told Mekong Eye.

“This is a battle to save nature, ecological benefits, the livelihoods of communities and everything that the Saola species represents,” Thinh emphasized.