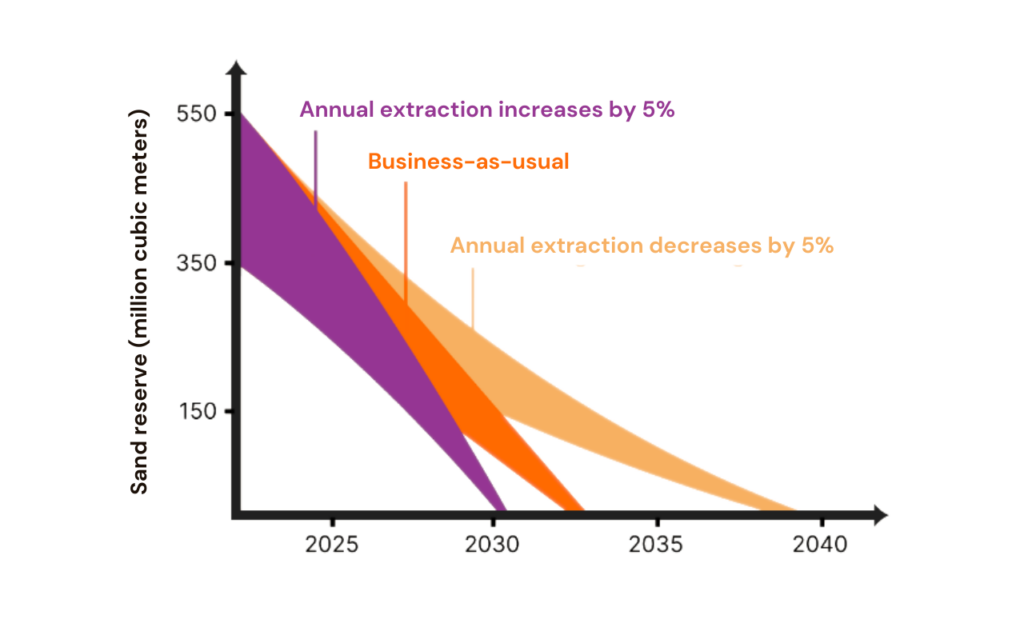

MEKONG DELTA, VIET NAM – Viet Nam’s Mekong Delta may run out of sand by 2035, according to a groundbreaking report published by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), based on how much sand is being extracted annually.

The report estimated that sand is now being extracted at 35-55 million cubic meters annually, 14 to 17 times the amount naturally replenishable by the upstream part of the Mekong River, which is estimated at a mere 2-4 million cubic meters per year.

If the extraction rate decreases by 5%, the entire sand reserve now estimated at nearly half a million cubic meters will still deplete by 2040, the report predicted. The exhaustion of sand stock will not only halt construction projects, but also expand areas affected by saltwater intrusion by 10-15%, roughly 2-3 times the size of Ho Chi Minh City.

Observers have lauded the Sand Budget report for being the first to take stock of this scarce resource. It also opens up new avenues for public discussion: what is to be done given the sand reserves won’t last?

As the sand market heats up and talk of a sand scarcity takes central stage, experts in Viet Nam have started to ponder a variety of policy and technical solutions to manage this diminishing resource.

Getting the price right

In all scenarios, the report predicts doom for the Mekong Delta – commonly known as the country’s rice bowl – in less than two decades.

“Sand mining cannot be stopped, but based on the [report’s] results, we need to determine how to exploit sand, what extraction scenarios are appropriate, and how to minimize the environmental impact,” said Nguyễn Nghĩa Hùng, the Deputy Director of the Southern Institute of Water Resources Science.

“The first step is to adjust the plan, re-evaluate extraction zones, research technological, engineering and design solutions that use less sand,” Hùng added.

In the same vein, Can Tho University’s Associate Professor Lê Anh Tuấn argued that a combination of sand management policy and technical solutions were necessary to slow the depletion. “We need to prioritize sand extraction for critical projects,” Tuấn said, referring to various ongoing highway projects in the Delta.

“Traditional construction methods like sand embankments are wasteful. We should consider technical solutions such as building elevated highways with viaduct structures to minimize sand use,” Tuấn added, noting that such alternatives may cost more in the short run, but safeguarding the sand reserves and enhancing the region’s climate resilience are critical to stability in the long run.

For others, the current sand prices are not accurately reflective of its true value.

WWF Asia-Pacific’s Freshwater Program Manager Marc Goichot argued that although sand holds significant economic value, it has an even greater value in protecting the Mekong Delta from the impacts of climate change.

At present, sand is only evaluated based on extraction and transportation expenses, without assessing the environmental costs of its removal from riverbeds and loss of the Delta’s recovery capacity.

“Sand has many values to the economy once it is extracted from the river, yet it has greater value when it stays in the rivers and coasts as if offers there the most cost-effective protection from the effects of climate change,” Goichot said.

Rising sand prices

But before sand can be evaluated for its true value, its market price is already heating up.

After the arrest of 18 people for their involvement in illegal sand mining in An Giang province in August, sand supplies in the Mekong Delta immediately became scarce. Sand prices soared to unprecedented levels, and many construction projects were put on hold.

A sand supplier for eight construction projects in the region, who wished to be identified only as ND, revealed in September that the price of sand purchased at the quarry was about 120,000 VND (US$5) per cubic meter (m³), but sold at construction sites to suppliers like ND in Can Tho at 320,000 VND ($13) per m³.

Suppliers, meanwhile, can only sell sand to contractors at 180,000-220,000 VND ($7.3-9) per m³, resulting in a loss.

“No one can afford that,” ND said.

This is not the first time, however, that the sand price and supply have fluctuated. “In the Mekong Delta, the mere mention of an inspection or an audit is enough for many sand miners to halt operations and for the sand supply to drop,” LHN, a construction investor based in Can Tho City, disclosed.

“There were times when our construction projects had to pause for an entire month waiting for sand,” LHN added.

ND believes that crackdowns on illegal miners and a rising sand price will eventually become beneficial for authorized extractors as the market stabilizes.

“We want transparency,” ND said. “When the sand supply is transparent, the market price of sand may rise, but good management will ensure long-term stability. Projects won’t have to worry about supply fluctuations, and businesses won’t have to worry about price fluctuations.”

While technical solutions to minimize sand use are not yet rolled out, preferential treatments to critical construction projects have started to create winners and losers.

LTL, a sand dealer for the Can Tho-Ca Mau expressway project, was optimistic about securing more than 200,000 m³ of sand for the contract his company had won, following months of struggles to locate supply sources.

“After this incident [in An Giang], the miners may slow down supply, but they will certainly have to prioritize expressway projects, following the government’s directives,” LTL said.

LTL explained that before the government tightens regulations and cracks down on illegal miners, sand suppliers preferred commercial projects for they could sell at a higher price with less paperwork.

“Aside from higher prices, they could also falsify invoices. An invoice for 5,000 m³ of sand sold can appear as 500 m³,” said LTL, detailing one of the ways suppliers can sell more sand than the quota allotted.

“Previously, invoices should be sufficient. But now you must show proof of the transport’s starting and ending points. Therefore, supplying sand for expressways is now the safer option,” LTL added.

While favor has tilted towards expressway projects, other civil construction projects deemed non-critical are bearing the brunt. T, the owner of a sand mining business in An Giang, had to turn down a district authority’s request to provide several thousand cubic meters of sand for a low-income housing project.

“According to current regulations, the source of sand must be provided for critical projects approved by the provincial People’s Committee. So, even though I really want to supply sand for low-income housing projects, I dare not. Something might go wrong, and my permit could be revoked,” T said.

According to sand supplier ND, non-critical construction projects can now only import sand from Cambodia at exorbitant prices.

“Currently, 1 cubic meter of Cambodian sand, brought from the Vinh Xuong International Border Gate (An Giang) to Can Tho, costs 280,000 VND ($11.4) per m3, and 380,000 VND ($15.4) per m3 when delivered to construction sites. Even at this price, they won’t deliver it without full advance payment,” D said.

This article was originally published as four separate articles in Vietnamese in Thanh Nien newspaper. They are Đồng bằng sông Cửu Long còn bao nhiêu cát?; ĐBSCL trước nguy cơ hết cát; Tính đủ giá trị của cát, đừng lãng phí, and Miền Tây đứt gãy nguồn cung cát. The English translation and editing were provided by Mekong Eye.