อ่านบทความภาษาไทยที่นี่

KANCHANABURI, THAILAND ― While wild tiger numbers have been shrinking across Southeast Asia, their numbers have been steadily increasing in Thailand, as recent sightings show.

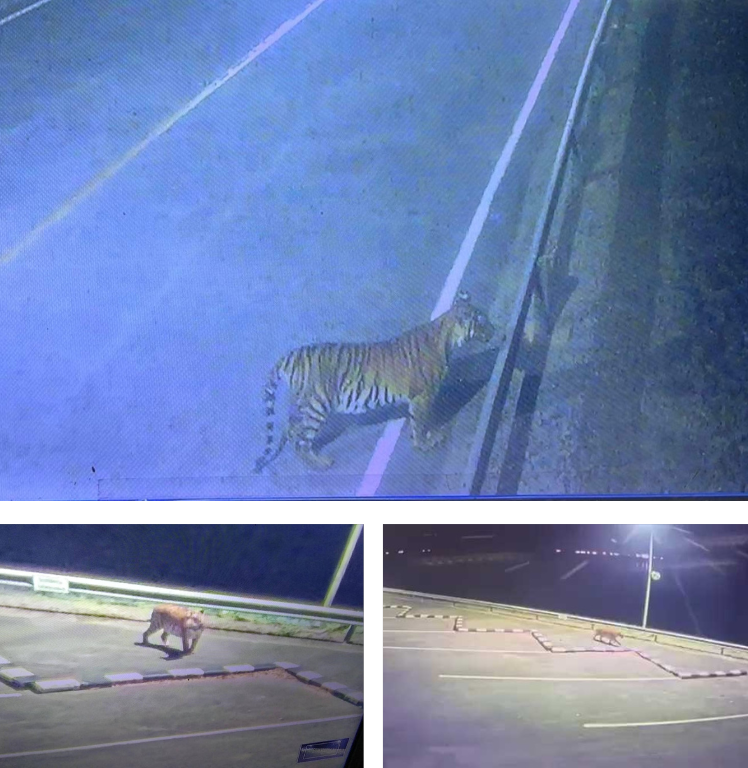

Codenamed SLT002, a young male tiger stopped to look over a fence on a ridge near the Srinagarind Dam in Thailand’s western Kanchanaburi province, close to the border with Myanmar.

It was a cold January night and pitch-dark at 2am, save for the streetlamp in the parking lot, which he also walked past, not knowing the CCTV cameras had been capturing his every move.

He was far from being scrawny, which might explain his venture into the human domain. In fact, he looked perfectly healthy.

“He was probably young, and foolish. He probably had never faced a threat in his life,” said Rattapan Pattanarangsan, the Conservation Program Manager at Panthera – an international organization devoted to the study of feline species worldwide – of the young tiger codenamed SLT002.

“And his appearance was very unusual,” he added.

SLT002’s appearance caused quite a stir and made headlines in Thailand. Warnings were issued in nearby communities and people there were told to exercise caution.

The Srinagarind Dam is a popular tourist spot. Kanchanaburi province draws visitors from all over the world to see its many natural and historical attractions like the River Kwai Bridge, built during WWII by prisoners-of-war overseen by the Japanese army.

After the incident with the young tiger, Panthera was able to identify, by his unique stripes, that the cat had been captured some months earlier in the wild on a camera trap, part of the conservation effort in partnership with the Thai government that has run for the past decade.

Apart from the scare it provoked, SLT002’s appearance was, after all, a sign of hope. New tigers often expand to new areas where they can dominate and their habitat in Thailand’s western region remains the only spot in mainland Southeast Asia where they can find sanctuary.

Overall numbers dropping

Since the turn of the 20th century, the global tiger population has dropped by 95%, from approximately 100,000 individuals to as low as 3,200 in 2010. The number, however, rose to 4,500, as reported by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), in 2022.

There are no more tigers being detected in Laos or Cambodia, said Rattapan. In Thailand’s Khao Yai National Park in the northeast, the last tiger was killed 40 years ago, according to Panudet Kerdmali, the secretary-general of the Sueb Nakhasathien Foundation, a conservation group.

In Myanmar, information and the study of tigers is impossible because of the ongoing fighting that prevents access to many areas. In Malaysia, animal trappers using wire snares have caused a drop in the number of animals left in the wild.

However, a number of countries – including India, Nepal and Thailand – have been an exception.

“These are the ‘yolks’ of tiger and wildlife conservation,” said Rungnapa Phoonjampa, a researcher at the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Thailand.

The number of wild tigers in Thailand has grown. There are 148-189 tigers in the wild now, compared with 130-160 in 2020, according to Thailand’s Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP), which is in charge of the tiger conservation program.

Thailand first issued a Thailand Tiger Action Plan in 2010, and it aims to be a regional leader in tiger conservation by 2034.

To date, there are more than 1,200 locations in the wild where camera traps have been installed.

The DNP works in partnership with organizations like Panthera and WWF, among others, on a range of projects including the camera trap installations, training and support of park rangers, as well as educating communities about conservation.

In four designated parks in Thailand’s Western Forest Complex (WEFCOM) – including Mae Wong National Park, Khlong Lan National Park, Klong Wang Chao National Park and Umphang Wildlife Sanctuary – the WWF has worked on its tiger conservation project since 2012, said Rungnapa.

Twenty tigers and five cubs – aged less than two years old – were recently detected by the WWF’s cameras in 190 locations in those four parks, the researcher added.

Panthera operates in the Salakpra Wildlife Sanctuary in Kanchanaburi in the southern part of the WEFCOM, the largest remaining forest track and one of the most ecologically diverse lands in mainland Southeast Asia that extends well into Myanmar, covering some 18,000 square kilometers.

Since its work started in 2014, the tiger population has been on the increase, according to the information gleaned from the camera traps Panthera installed in more than 400 locations.

New hunting grounds

As the tiger population rises, their hunting grounds will also expand, said Panudet, from the Sueb Nakhasathien Foundation. As a result, cases of wandering cats like SLT022 will be more frequent.

“Two types of tigers will be forced to find new hunting grounds: a cub that has just separated from its mother and the aged tiger whose hunting skills have diminished and they have to face younger and stronger newcomers in the area they have dominated.”

In Kanchanaburi’s Thong Pha Phum district in January 2022, five men were charged with hunting and killing two tigers after skinning and butchering them. The poachers said the tigers had eaten a number of cattle in their communities, so they were shot.

Some local officials were quoted as saying that the alleged offenders had skinning skills. A tiger skin can be sold, or trafficked to countries like China and sold, for as high as one million baht (US$27,000), said an officer.

“At the moment, Thailand’s tiger population in the wild is not high enough to stabilize,” said Panudet. “So dealing with poachers, working with the local communities and increasing prey in the wild is the key to sustaining the tiger population and to preventing incursions with humans.”

Michael Roy, WWF Thailand’s conservation director, said the core of the Tiger’s range is in the Thung Yai-Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the middle of the WEFCOM, which means there is an equilibrium between the hunters and prey in that area.

In other areas, however, “poaching led to reduced prey in decades past … so the population, of Sambar deer for example, does not re-establish themselves, so we have to be a catalyst for that by rearing animals in captivity and releasing them in the wild.”

“Tiger is an indicator of abundance. For example, a tiger could eat one deer per week. So we need a significant number of deers all year round as prey,” added Rattapan from Panthera.

“A female tiger hunts within a 60-square-meter area, a male tiger needs between 200 and 300 square meters to hunt and they need an abundant life support system such as water and air.”

On a September morning, a team of four of Panthera’s researchers went on foot into Salakpra to install cameras. These researchers tie a camera to a tree using wire and position the camera about 45 to 60 centimers from the ground to capture photos of tigers.

In each spot, two cameras were placed opposite one another, so the tiger’s stripes could be recorded on both sides of its torso for identification.

The cameras usually last for months unless animals like elephants feel they need to rip the strange thing off the tree, said Waraphon Panomwongkasem, the Panthera Tiger & Leopard WEFCOM Research Project Manager.

They set off with a number of park rangers who provide safety – the terrain can be challenging, and unexpected things can happen, like running into wild animals or other humans.

Despite the camera traps, tigers, whose lifespan is estimated to be between 15 and 20 years, are still an enigma to researchers as none of the cameras could witness its whole life cycle from birth to death, said Waraphon.

But some shots were fascinating, showing further signs of new tigers settling in Salakpra.

In 2021, a female tiger was caught on camera. Her cub, which was almost as big as her, was trailing close behind, said Waraphon. “We knew it was her cub because it’s not often that two tigers from separate families ever live together.”

Paitoon Indharabut, the head of the Salakpra Wildlife Sanctuary, showed a video clip, obtained from a researcher, of a little puddle that was filled by rain one night and the next morning a tiger slowly approached the puddle before sitting down on its four legs and slurping the muddy brown water undisturbed.

As a wildlife sanctuary, Salakpra is out of reach to the general public, but Paitoon and his team have often come into contact with poachers and woodcutters.

Sometimes, the incursions are like a scene from a movie. Park rangers rely on intelligence to get wind of local poachers. Several years ago, he and a team of about a dozen hid out in the forest to catch them. They don’t have the authority to detain or interrogate, only to hand them over to the police.

Part of Thailand’s tiger roadmap includes smart patrolling – a system which focuses on detecting signs of animals, poachers and others using technology like GPS to navigate. Partner organizations like WWF and Panthera also support training and equipment for rangers.

Paitoon commands a team of about 160 park rangers whose jobs require them to patrol for at least 14 days in a month. Their salaries range from 9,000 baht to 15,000 baht ($247 to $412) per month.

There are more than one dozen ranger stations in Salakpra and the park allocates a weekly budget for food and supplies. Stations are often a group of shacks with only the basic necessities, but “if you don’t love it here, you cannot be here,” he said.

This story was supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.