Đọc bản tiếng Việt tại đây.

SÓC TRĂNG, CÀ MAU & THÁI BÌNH, VIET NAM – One October morning, despite the seasonal demands of rice harvesting and onion planting, the community forest protection team in Vĩnh Châu commune in Sóc Trăng province still meet to report on each and every mangrove shrub they have inspected.

The Vĩnh Hải Forest Ranger Unit has only nine rangers who oversee 4,300 hectares of forests stretching 43 kilometers, so coastal residents, often dubbed “the people’s ears and eyes,” are also recruited. Their task is straightforward: rushing to the coast at the first sound of an axe being used.

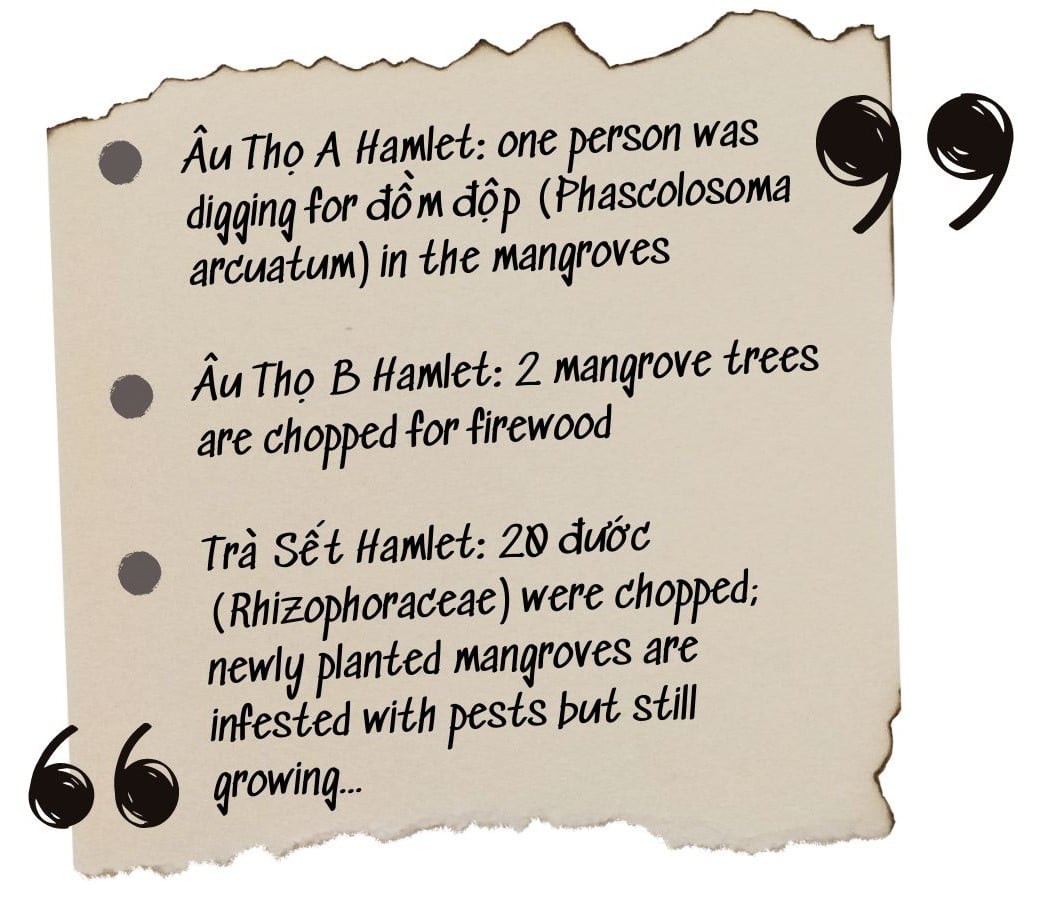

Illustration: Extracts from reporter’s records of Vĩnh Hải community forest protection team’s meeting on October 24, 2023.

The surveillance is meticulous. In the third quarter of 2023, the Sóc Trăng Forest Department fined two people who illegally felled 18 bần and mắm trees (Sonneratia caseolaris and Avicennia) for firewood, one who chopped into a water pipe and one who planted coconuts in the mangroves without authorization.

“[If you] want to hire someone to dig a one-meter-wide trench to farm mudskippers [in the mangroves], the province’s vice-chairman will personally come to inspect,” Thạch Bun Thol, the head of Âu Thọ B hamlet’s forest protection team, told a reporter.

Sóc Trăng is not the only province in Viet Nam’s Mekong Delta employing stringent monitoring of its mangroves. In Cà Mau, provincial leaders say they demand that everyone on the team “knows the forest like the back of their hands,” especially after a series of natural disasters in the early 2000s.

“The Cà Mau peninsula is a lowland, alluvial plain. Without mangrove forests, can you imagine the extent to which climate change and rising sea levels will affect the infrastructure and livelihoods in Cà Mau and the entire delta,” said Trần Văn Thức, the Deputy Director of Cà Mau province’s Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

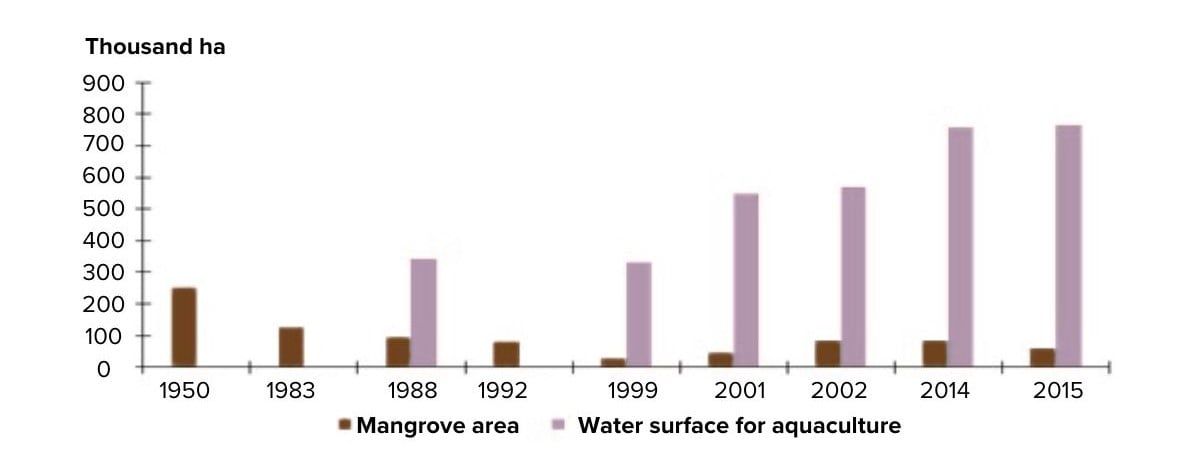

Despite the fraught efforts, more than three decades of forest land conversion to aquacultural and other economic purposes, compounded by rising sea levels and human-induced coastal erosion, led to many of the mangrove forests being steadily decimated in a number of provinces in Viet Nam.

In Cà Mau, the country’s largest and lushest mangrove reserve, more than 50% of forest areas were converted to shrimp farms between 1973 and 2008. Xuân Thủy National Park, the first Ramsar site in Vietnam and a core part of the UNESCO-recognized Red River Delta Biosphere Reserve, has been able to retain only about 37% of its forest area compared with 1986.

In Sóc Trăng, from 1988 to 2018, the mangrove forest area decreased by 55%. In Bạc Liêu, the drop was as high as 90%.

The mangrove ecosystem not only nurtures and protects the country’s largest deltas, but also exerts significant economic and social influence – the full extent of which EIAs (Environmental Impact Assessments) have yet to fully quantify.

A tangle of roots alone forms a small forest that can filter seawater and serve as a nursery for fish, crustaceans and mollusks. It is estimated that up to 90% of marine species spend part of their lives in mangrove forests, either breeding, maturing or residing, and 80% of global seafood harvesting relies on this ecosystem.

The loss of mangrove forests is not unique to Viet Nam. In Thailand, as of 1993, an estimated 38%-65% of mangrove forest areas had been converted into shrimp farming ponds. Globally, 35% of mangrove forest areas disappeared between 1980 and 2000, primarily due to human activities, the largest contributor being forest land conversion for aquaculture and agriculture.

As the majority of mangrove forests now lie at elevations close to the water inundation threshold, in about 30 years, there is a 95% chance that mangrove forests worldwide will no longer exist due to sea levels exceeding the capacity for sustainable sediment accumulation and the forests’ tolerance to inundation.

From mangroves to shrimp farms

Shrimp farms next to mangrove forests in Vĩnh Châu, Sóc Trăng. PHOTO: Thành Nguyễn.

“It used to be all forests around here,” recalled Nguyễn Hưng, a resident of Huỳnh Kỳ hamlet in Vĩnh Hải commune in Sóc Trăng province, who wished to speak under a pseudonym. In the 1980s, his family did extensive farming in a mangrove forest near his house.

They cleared some land to build a channel, enclosed it with a net, drained the water twice a month, then harvested the shrimp and fish. Tides naturally brought in shrimp, crab and fish larvae, which thrived on the abundance of phytoplankton under the forest.

His wife and daughter, meanwhile, foraged for mussels, clams, and blood cockle larvae in the mangrove to sell them to other farmers. They earn about 100,000 VND (US$5) a day, a small amount yet enough for the daughter’s school supplies and bus fees.

“During high tides I can even catch mullet and horseshoe crabs,” said Hường, Hưng’s wife, who also wished to speak under a pseudonym.

Later for many people, relying solely on the forests was no longer enough. During the early 1990s, families in Hưng’s areas and the wider Mekong Delta started to switch to intensive farming, triggering a boom in Viet Nam’s shrimp industry.

Intensive farms spread quickly, not only because of promising profits, but also the deltas’ geography. Extensive farms have no physical boundaries, and in the Mekong Delta, water flowed freely between some 26,000 rivers, streams and canals. It was challenging, if not impossible, to control the water quality in both extensive and intensive farms.

“I was farming greasyback, whiteleg shrimps and crabs extensively, but when everyone around me started to bulldoze their ponds, pump chemicals in and drain their water, I had to follow suit,” Hưng explained. “If I had not converted to intensive farming, when my pond was flooded with the contaminated water, my shrimps would have been dead.”

Hưng then cleared and burned the mangroves, leveled the banks and turned the plot into two one-hectare shrimp ponds. The heydays quickly arrived as the newly cleared land was not yet infected with diseases. For two consecutive years, the income was plentiful. Hưng bagged a total of 200 million VND ($8,146), which he used to renovate his father’s house.

Only three years later, Hưng could not explain why he lost two shrimp harvests in a row. “It was almost harvest time and my shrimps fell sick, swelled up and died en masse,” he recalled.

Unable to stomach the cost of 70 million VND ($2,851) on soil repair, new larvae, medicine, chemicals and oil, Hưng abandoned both of his ponds. Dozens of ponds near his house were also left unattended or leased out to fish farmers – people with more capital than shrimp farmers.

Fish are less prone to diseases but take two years to harvest instead of a few months.

Similar stories have unfolded in the Red River Delta. An, who wished to speak using a pseudonym, is a highly experienced farmer in both extensive and intensive shrimp farming in the Mekong.

When returning to his hometown in Cồn Đen in Thái Đô commune in Thái Bình province, he refused to set up his own farms. Having seen too many unpredictable harvests, he decided that working as hired labor for farm owners was a better way to earn money.

“The water around here is uncontrollably contaminated,” An told the reporter, convinced that he was 70% likely to fail if he started his own farm.

Many farmers in both deltas told the reporter they believed that once the mangroves were felled and chemicals applied for intensive shrimp farming, the soil would become too hardened for the mangroves to return.

Economic pressure, rising sea levels

Part of mangrove forests destroyed by waves in Vĩnh Hải, Vĩnh Châu, Sóc Trăng. PHOTO: Thành Nguyễn.

While shrimp farms inched into mangrove forests gradually over a few decades, coastal soil erosion took hundreds of hectares at once. Cà Mau province loses 300-400 hectares of mangroves annually to erosion, according to Thức. The accumulated area in the past 10 years can be comparable with the size of a small town.

From 2003 to 2012, the entire Mekong Delta has lost approximately 2.3 square kilometers of coastline annually. The loss is largely human-made. Upstream dams and excessive sand mining have significantly reduced the sediment loads in the Red River and Mekong River by approximately 91% and 74% respectively, making it increasingly difficult for mangroves to form.

Meanwhile, the construction of coastal dykes to protect residential areas, infrastructure and aquaculture zones further diminishes the natural ability of the remaining mangrove forests to dissipate waves.

From satellite data, mangrove areas have increased slightly in recent years, thanks to afforestation and construction of embankments to protect the newly planted forests. The new areas, however, can barely compensate for what was lost, according to Trần Văn Thức, the Deputy Director of Cà Mau province’s Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, and Võ Quốc Tuấn, the head of the GIS & Remote Sensing Laboratory at Cần Thơ University.

“If stronger measures are not implemented to expand forest areas faster, it will be very difficult to combat coastal erosion,” said Tuấn.

Soon, large-scale hydroelectric dams, rapid subsidence and rising sea levels will worsen coastal erosion in the Mekong Delta. Mangroves require periods of inundation and emergence to breathe, and if the sea levels rise beyond their tolerance thresholds, the forests will suffocate and die from prolonged submergence.

Urbanization and other development activities have also taken a toll on mangrove forests in the past 30 years. In Rạch Giá City in Kiên Giang province, infrastructure projects have largely decimated mangrove forests, with only 1% of the city’s total area now remaining covered by mangroves.

Mangrove forests which once spanned more than 20% of the land area in Trà Cú district in Trà Vinh province have now nearly vanished as a result of industrialization.

Environmental impact

assessments re-examined

A patch of mangrove forest. PHOTO: Thành Nguyễn

To recognize the full value of mangrove forests, and make informed policy decisions to either protect, afforest or accept economic trade-offs, the way environmental impact assessments are done in Viet Nam must be re-examined.

“Mangrove forests are currently a good tool to adapt to rising sea levels due to climate change, while other solutions such as coastal embankments are more costly and risky,” Phạm Khánh Nam, from the Economy and Environment Programme for Southeast Asia (EEPSEA) at the University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, told Mekong Eye.

“However, mangroves’ ability to prevent erosion and protect the coasts is often overlooked in policy analyses for land conversion.

“Calculations in Viet Nam usually show that industrial shrimp farming generates more monetary benefits per hectare than mangrove forests,” Nam added. EIAs often ignore biodiversity, non-use and the carbon sequestration values of mangrove forests, he added.

Even when carbon sequestration is included, the calculations are not accurate, he said. For example, some studies estimate the price of 1 ton of carbon at about $11, but the real value may be six-fold.

“The benefits of mangrove forests are, in many ways, societal. They provide timber and seafood for coastal residents, protect them from erosion, regulate the climate for the national and global population. These values cannot be expressed in monetary terms, but often manifest in increased welfare,” Nam contended.

When trading off mangrove forests for industrial shrimp farming or other economic projects, the forests’ values are measured in monetary terms and reserved for investors. “However, if we consider the impacts on distribution and equity, mangrove forests excel by a large margin,” Nam said.

According to the researcher, EIAs must include consistent and accurate data on forest status, evaluations of forest-related activities, indirect and direct impacts of forest loss, as they are done globally. In Viet Nam, EIAs stop short at project description, waste discharge, collection and treatment and community consultations – without tallying values that can be forever lost.

In addition, in a mangrove ecosystem, environmental impacts upstream will likely lead to consequences downstream.

Remaining hopes

Mangrove forests are closely intertwined with delta residents’ livelihoods. PHOTO: Thành Nguyễn

Eco-agritourism, an emerging solution in the Mekong Delta, is meeting such problems with upstream-downstream linkage.

In Năm Căn and Ngọc Hiển, part of the Đất Mũi National Park and Protection Forest, eco-shrimp farmers are made to eliminate chemicals, feed and probiotics, yet the water channels across the region are closely connected.

“In Rạch Gốc and several other areas, industrial farming is allowed, but the water is not treated well. Even when the shrimp get sick and die in large numbers, the water is still discharged into the rivers and into my pond. Upstream discharges contaminate our downstream flow,” Nguyễn Tấn Lợi, a farmer in Viên An commune in Ngọc Hiển district in Cà Mau province told Mekong Eye.

Like Lợi, many farmers in Viên An have suffered complete losses of their eco-shrimp crops. Yet, the majority of farmers owning less than three hectares of land, who account for 30-40% of Cà Mau eco-shrimp farmers, are quietly expanding their shrimp farming zones to their assigned mangrove forests, failing to maintain the required forest cover of 60%.

“It is too late to control diseases from intensive shrimp farms in such a dense canal system,” said a Vietnamese biologist specializing on crustaceans and now working in Europe who wished to remain anonymous.

“Shrimp diseases have been circulating in this [Mekong] delta for 20 years, since we imported foreign larvae and bred them to serve the booming industry,” he added.

The only prospect for eco-agritourism, according to this researcher, hinges on the preservation of mangrove forests and their ability to filtrate water, as it is very difficult for any province to isolate their water source.

The question remains for abandoned land too contaminated for shrimps to survive consecutive crops. Pointing at his deep, hardened ponds, Hưng told the reporter he now planted onions and watermelon, and worked as hired labor to earn money.

His wife still collects mussels in a nearby muddy plain, once part of a thriving mangrove forest but now decimated by coastal erosion.

Precarious future

Hưng’s wife, Hương, and their daughter collect mussels in the muddy plain which was once a mangrove forest. PHOTO: Thành Nguyễn

As the fate of Viet Nam’s two largest river deltas and coastal communities hangs in the balance, the destruction of mangrove forests continues. In April 2023, Thái Bình province in the Red River Delta decided to convert part of the Tiền Hải Nature Reserve into an urban and economic zone.

The decision sparked controversy, as the area was part of a UNESCO-recognized Red River Delta Biosphere Reserve, playing an integral role in mitigating the impacts of storms and carbon sequestration. Thái Bình authorities did not respond to requests made in November 2023 for comments.

Thạch Bun Thol, the forest protection leader in Âu Thọ B hamlet, remembers vividly the 1995 tsunami that destroyed all the poplar trees, and storm Linda in 1997 that claimed more than 3,000 lives, as well as decimating houses and farmland.

After the disasters, local residents, including Bun Thol, replanted the coastal mangrove forest. Three decades later, the strip has been covered with mangroves, and the trees have grown old enough to protect the villages.

“Three years ago, [we were] hit with large waves at night but I was soundly asleep,” Bun Thol recalled.

“I only realized the next morning when I saw my sandals floating. The mangroves stopped the waves. Water rose so slowly and smoothly I did not even notice.”

This article was first published in Vietnamese in the Tia Sáng magazine on January 28, 2024. The article was re-edited and translated into English by Mekong Eye.

Reference

*Phạm Khánh Nam et al., “Mainstreaming natural capital into sustainable development policies and actions – a rapid assessment of mangrove ecosystem services in the Mekong Delta,” 2018.