Đọc bản tiếng Việt tại đây.

BẠC LIÊU, VIỆT NAM – For about six months each year, the one-hectare farm of 64-year-old Lê Tấn Lập in Bình Tốt B hamlet in Phước Lộc district has been home exclusively to the giant tiger prawn – a saltwater species. For the rest of the year, giant freshwater prawns and rice share the land.

This intercropping, rotational model is what Vietnamese farmers call “shrimp-on-rice” (con tôm ôm cây lúa in Vietnamese) – a new variation of the shrimp-rice rotational model hailed as a climate adaptation solution to saltwater intrusion in Viet Nam’s “rice bowl” – the Mekong Delta.

Lập lives and farms next to a 40-kilometer-long seaward canal, where tides and floods frequently alter saltwater and freshwater flows. During the dry season in November to May, he lets seawater into the field to raise giant tiger prawn.

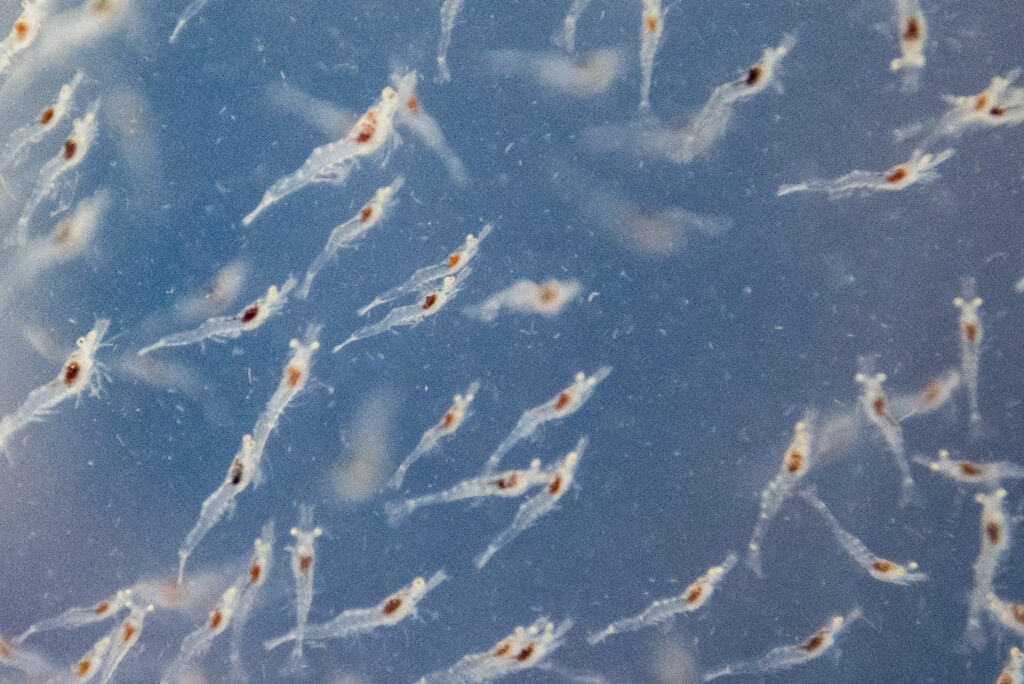

Upon harvest, he pumps in freshwater and then dries out the soil. At the start of the rainy season in July, as rainwater further dilutes the salinity, he switches to giant freshwater prawns which have a high tolerance for salinity during their breeding season. Two months later, he adds rice to the mix.

Lập has tested various farming models to combat soil salinization over the past few decades, but “shrimp-on-rice” seems to be the most promising so far, he says.

Since 2017, he has earned on average an annual profit of US$810-1,210 (20-30 million VND) from rice and $2,430-3,240 (60-80 million VND) from the shrimps, higher than all past models.

“Rice purifies the water and shrimps feed on rice plants’ nutrients,” Lập told Mekong Eye. “If the temperature rises erratically, rice plants will provide shade and mitigate the sudden rise in water salinity.”

“The intercropping, rotational rice-shrimp farming method is a model for farmers to adapt to changing water resources and the climate, while reducing negative impacts on the environment,” said Dương Nhựt Long, a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Fisheries at Cần Thơ University.

According to a report from the Directorate of Fisheries in 2022, the shrimp-rice rotational model covers about 25% of the total shrimp farming area in the Mekong Delta – 190,000 of 747,000 hectares. Shrimp-rice farmers produce about 100,000 tons of saltwater shrimp and more than 20,000 tons of giant freshwater prawn, from a total 1.08 billion ton.

In Bạc Liêu province, the “shrimp-on-rice” model, though occupying a modest area, is expanding rapidly. Between 2017 and 2023, its total area surged 21.6 times, from 600 to 13,000 hectares.

Farming with salinity

Lập first let seawater into his rice fields and started to farm giant tiger prawn in 1995, after several failed crops due to rising salinity.

The rotational shrimp-rice model started as experiments by farmers like Lập, but later gained government endorsement. In 2000, resolution No. 09/2000/NQ-CP officially allowed farmers to convert dry or salinized farmland to aquaculture and non-grain crops.

Lập continued to improve his techniques by attending training at local cooperatives. He transitioned from shrimp monoculture to two shrimp crops and one rice crop per year, before adopting the current “shrimp-on-rice” model.

Giant freshwater prawns feed on nutrients from natural sources such as algae and microorganisms from the rice plant, Lập explained as he chopped up small pieces of coconut meat and tossed them into the pond for the shrimp. Occasionally, he also supplements their diet with commercial shrimp feed to boost growth.

“It is more relaxing to farm giant freshwater prawns than giant tiger prawns,” Lập told Mekong Eye.

Soil salinization has shaped not only farming techniques, but also altered the agricultural ecosystem. Researchers have been developing rice varieties that can withstand salinity as well as saltwater shrimp species that thrive in brackish water.

According to the Bạc Liêu Department of Cultivation, the primary rice varieties grown in shrimp fields, ST24 and ST25, can tolerate low-salinity environments and have a harvest cycle of 90 to 120 days. Notably, ST25 was recognized as the best rice in the world in 2019.

To meet market demands, breeding practices for giant freshwater prawns has also evolved. In the early 2000s, Vietnamese breeders started producing artificially bred strains of these prawns, marking a significant advancement in revitalizing giant freshwater shrimp farming.

These days, giant freshwater prawns grown in rice paddies are primarily male, said Nguyễn Vân Sơn, the owner of a breeding farm in Cà Mau.

“Male shrimps are much larger, so there is a higher demand for them,” Sơn said.

In 2022, Việt Úc, a seafood company pioneering research and the breeding of broodstock in Viet Nam, introduced a white-legged shrimp breed with exceptionally low salinity tolerance, known as VUS Leader 1/000.

Whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) is a species commonly found in seabeds or areas with high salinity. According to a Việt Úc representative, this breed exhibits higher adaptability, faster growth, better survival rates and increased harvest counts.

Challenges remain

Despite being hailed for environmental friendliness, low risk and sustainability, the “shrimp-on-rice” model still faces significant challenges, said Lê Anh Tuấn, Senior Lecturer at Cần Thơ University’s Climate Change Research Institute. He stressed the need for quality control of rice seeds and shrimp larvae.

After his first try with VUS Leader 1/000 shrimp, 35-year-old Thái Phong Em from Thạnh Phú district in Bến Tre province was not happy.

Last year, Em started farming 150,000 VUS Leader 1/000 breeds, only to harvest them prematurely after 50 days.

“The survival rate was high, but their growth was slow,” he said.

“Typically, the shrimps would have reached harvestable size within 60 days. However, I noticed stunted growth and signs of white feces disease during that period,” he added. “Seeing no promising prospects, I opted to harvest them immediately without treating the disease.”

Lập’s rice crops last year also yielded poor-quality grain. “I sold all my crops and did not leave any for family consumption, but the profit was not as good as the previous year,” he told Mekong Eye.

He suspects he may have purchased counterfeit ST24 rice seeds instead of the authentic ones he intended to grow.

Besides breed instability, higher profits from shrimp farming might convince some farmers to abandon rice cultivation altogether, potentially disrupting the model.

Towards a sustainable model

Although hailed as a viable climate adaptation model, “shrimp-on-rice” needs to be improved on several fronts to become a truly sustainable model.

Alongside crop breed research and farmer training, Tuấn recommends investing in water storage ponds.

“The water storage ponds collect and store freshwater during heavy rainfall, offering a backup source for dry periods or high water salinity,” he said.

Long agreed. Integrating science and technology in agriculture boosts efficiency, cuts risks and optimizes resource use, he said.

“To achieve this, there should be collaboration among government, businesses and farmers to seek and implement sustainable solutions effectively,” he said.

Earlier this year, El Nino was forecast to return and extend into the 2024 dry season. Expecting freshwater shortages at the end of the season, Lập decided to sow his rice earlier than last year.

“I hope to be able to harvest before the saltwater intrusion comes,” he said.