AN GIANG, VIET NAM – In the dry season’s scorching heat, rice farmer Nguyễn Thành Thản stood in a soon-to-be-harvested field in Phú Hiệp district, surveying his crop and hoping for a fruitful season.

Despite having decades of farming experience under his belt, Thản was shocked to learn about arsenic contaminating rice.

“I had never heard of it before. I just noticed that there was less water this year,” he said, sighing after complaining about salinity, pests and the volatile global market.

Inorganic arsenic, a potent carcinogen, has been found in market rice grains from primary rice growing regions across the world, including Viet Nam. While concern for people’s health is growing, only a few rice exporters, such as China and Bangladesh, have paid attention to arsenic contamination in rice.

Like Thản, most Vietnamese farmers had not heard of the issue. Data on rice arsenic in the country is sparse, and policies are lacking.

“I had never heard of the possibility of arsenic in rice,” said Đinh Hồng Thái, Director of the Agricultural Service Center for Tháp Mười district in Đồng Tháp province in the Mekong Delta.

“I know there is arsenic contamination in groundwater, but how can rice plants absorb groundwater? I don’t think there is arsenic in rice,” Thái reasoned.

From ground to grains

Arsenic (As), an odorless, colorless and tasteless toxic metal, enters the human body through both the respiratory and digestive tracts. The average daily intake of total As from food and beverages ranges from 20 to 300 μg (microgram). Approximately 25% of As in food is inorganic, the potent variety of As.

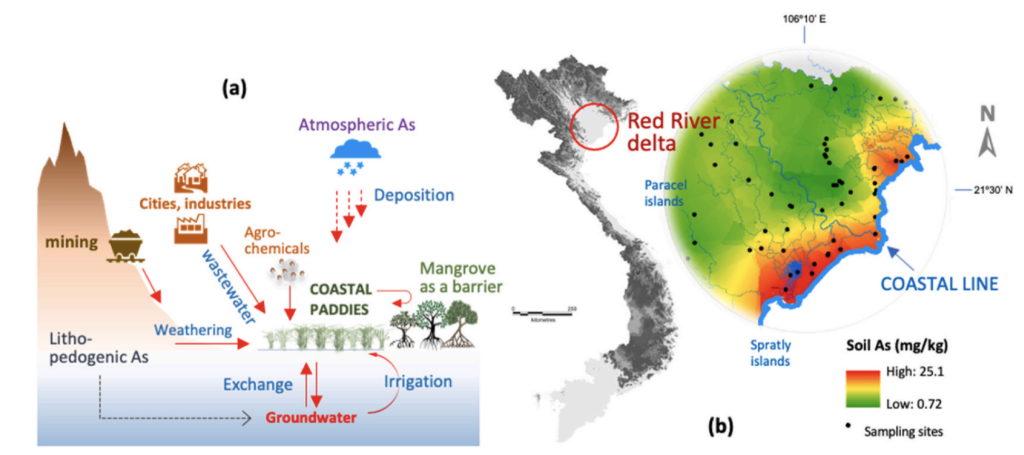

Rice is crucial to the diet of many cultures, yet it retains As levels 20-22 times higher than other staple crops. As can accumulate in rice grains if paddy soil or water for irrigation is As-contaminated.

Research has shown that long-term consumption of cooked rice with inorganic As levels higher than 180μg/kg can lead to DNA damage.

Given these health concerns, the Codex Alimentarius Commission, an intergovernmental body founded by the FAO and WHO, has limited the inorganic As level for polished rice to 200 μg/kg, and for brown rice to 350 μg/kg.

However, monitoring inorganic As in rice is a daunting task. So far, such explicit data for Viet Nam’s rice do not yet exist, but an estimation is possible based on total As data.

Research in 2023 which measured total As content in sample grains from 80 rice fields in the Mekong Delta showed a median concentration of 73 μg/kg, with values ranging from undetectable to 699 μg/kg.

In the Red River Delta, the median value was much higher at 221 μg/kg, with values ranging from 53 to 469 μg/kg.

According to the calculations of Dr Nguyễn Ngọc Minh from the faculty of Viet Nam National University in Hanoi who participated in research on both, such numbers are not explicitly alarming, given inorganic As in rice accounts for roughly 65-75% of total As concentration. However, since high values exceeding CODEX recommendations were found in various localities, further surveys and analyses are needed to clarify the risks, he said.

Tracing As accumulation is even more challenging. Minh said As concentration in rice can be affected by many variables – from farming techniques, As content in soil, plants’ absorption capacity to the soil’s physical, chemical and biological factors.

For example, in the Red River Delta, researchers found a significantly high median of total As in rice grains from lowland coastal areas (306.7 μg/kg), while As was not detected at all in rice terraces. As in soil contributes to As in rice straws and grains, yet in this case they could not find strong correlations among the three variables.

Meanwhile, As in soil in the Mekong Delta was found to be slightly higher than the global median, and is highly correlated with As in rice straws, but researchers did not find such a relationship from straws to grains.

The lack of correlations in both studies does not deny the soil’s role in the accumulation of As, but points to other factors excluded from research such as the nature of rice plants, soil properties or anthropogenic activities, the authors explained.

For example, changes in irrigation to adapt to harsher climate conditions can exacerbate As content.

In Viet Nam, more than one million wells have arsenic concentrations 20-50 times higher than the standards set by the Ministry of Health. Although most farmers in Vietnam usually do not use well water to irrigate rice due to high costs, during prolonged heatwaves causing water shortages, some farmers in the southern central region drilled wells and used mobile pumps to save their rice crops. This may have increased the arsenic content in their rice.

Alternative irrigation techniques

One way that farmers can mitigate As content in rice is through their irrigation techniques. Research has shown that flooded farming, which is still widely used by Vietnamese farmers, increases As mobility and accelerates the rice plants’ absorption rate of As.

“The more water, the better the rice grows,” said Nguyễn Văn Sáng, a farmer in Hồng Ngự in Đồng Tháp province. Flooded farming was the only way he knew since he started 50 years ago.

Minh says the popular practice creates ideal conditions for As to transform into a mobile form – one that can dissolve in soil and water, then move up the roots, stems and finally to the grains.

Managing water is the key to decelerating this process.

In recent years, the Plant Protection Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development has been suggesting farmers apply an AWD – an alternate wetting and drying – technique pioneered by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines to mitigate methane emissions in rice production.

Farmers are advised to let in a water level of 3-5cm deep, then wait until the field surface cracks slightly before irrigating the fields again.

Viet Nam aims to develop one million hectares of low-carbon rice by 2030. At present, the method has been piloted on 184,000ha of rice fields across several provinces in the Mekong Delta, such as Đồng Tháp, Cần Thơ, Trà Vinh and Bạc Liêu.

Minh says such low-carbon rice methods inadvertently help reduce As content in rice grains.

“The more water, the more mobile As is. When we flood and drain the fields, As will be fixed during the drying period, thereby minimizing accumulation in the rice plants,” explained Minh.

Research has shown that inorganic As content in rice grown with AWD is 27% lower than that of rice grown using flooded farming. A 2016 study in An Giang province also showed a similar result, with a reduction of 35.1%.

Stronger standards

Apart from alternative farming practices, it is not easy to remove As from either rice grains, soil or groundwater. Minh says adding certain compounds to soil can help convert active As to fixed As, making it difficult for plants to absorb. However, this method is costly and not easy to scale up.

Meanwhile, various human activities such as mining and the use of chemicals in farming can continue to deposit large amounts of As into soil. In addition, future climate stresses can cause rice plants to absorb more inorganic As from soil and water.

Several rice exporters such as China and Bangladesh have started to take the first steps. In 2005, China became the first country to set a limit for inorganic arsenic in rice – 150 μg/kg in 2005 and now 200 μg/kg. It has also invested in research to monitor As accumulation in rice fields across the country. Bangladesh has designed a number of toolkits to help farmers measure As in rice on-site.

The national standards system of Viet Nam (TCVN) now sets a limit for As in white fragrant rice (both polished and unpolished) which is 1.0 mg/kg, the equivalent to 1,000 μg/kg.

Minh says this threshold is too high.

A code of practice for preventing and reducing As contamination in rice based on CODEX standards, however, is being developed by the National Technical Standards Board, revealed Lê Thành Hưng, head of the Department of Agricultural and Food Quality Standards at the Viet Nam Standards and Quality Institute.

The study of toxins in food is a sensitive issue in Viet Nam as it easily triggers a public outcry and affects exports. Minh, however, believes that early risk analysis will bring long-term benefits.

“As a country that produces and exports rice, Viet Nam needs to promote research and transparency on the issue of As accumulation in rice,” he said.

This article was first published in Vietnamese in Tia Sáng Magazine on May 8, 2024. It was translated to English by Anh Lưu and edited by Mekong Eye.