LẠNG SƠN, VIỆT NAM – Every day between March and May and from August to October, women and men in their forties in Hữu Lũng free-climb limestone cave walls with their bare hands, searching for what they call “night sand.”

What they are searching for are small black pellets rich in nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, otherwise known as bat droppings, or bat guano. At the entrance to the caves, traders wait patiently to buy the natural fertilizer at US$3 per kilogram (70,000 VND), more than four times the price of synthetic NPK fertilizer.

Although collecting bat guano gives people a vital livelihood, scientists are concerned the practice poses high transmission risks of zoonotic diseases, and current policies are insufficient to prevent future pandemics.

“Bats, as well as wildlife species such as pangolins and civets, are known carriers of many diseases,” said Dr Vũ Đình Thống, a researcher at the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, who has spent more than 30 years studying bats.

“With their ability to fly and migrate over long distances, bats can spread viruses much more easily than other animals,” he added.

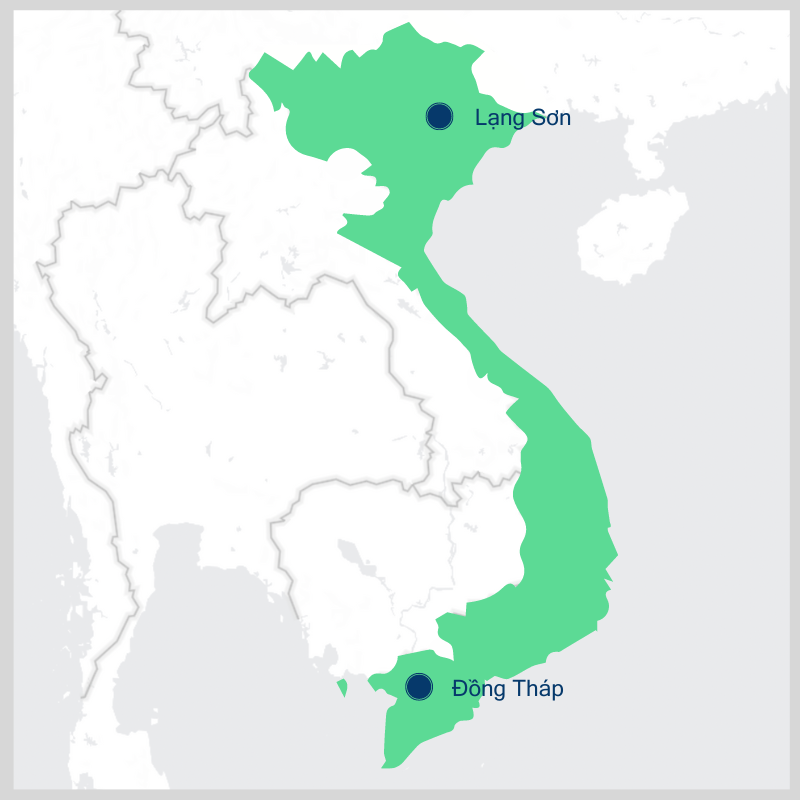

In Viet Nam, collecting guano is most prevalent in northeastern Hữu Lũng district in Lạng Sơn province, home to the largest bat population in the country, as well as the Mekong Delta, where guano farming dates back to the 1980s.

Decades-old contact

In the delta, people farm bats in their backyard.

A typical bat cage sits atop four concrete poles, elevated about 10 meters from the ground. Cage roofs are made from palmyra palm fronds, allowing the bats to nestle among the leaflets.

Bats sleep inside these cages during the day and fly out at night to hunt for food. Every few days, farmers collect guano on the tarps laid underneath the cages. The droppings are valuable, so farmers also comb through the palm leaflets to make sure they do not miss a pellet.

Many bat species visit these cages, but the regulars include the yellow house bat (Scotophilus kuhlii) and Chinese myotis (Myotis chinensis).

Guano farming dates back five decades, when orchards across the Mekong delta used the highly prized fertilizer, says Đinh Hồng Thái, Director of the Tháp Mười Agricultural Service Center. For farmers in Tháp Mười, collecting guano is as much a daily routine as cooking and cleaning, and they collect it without masks, gloves or any protective gear.

“I get bitten by bats all the time, but I don’t think it’s a problem,” said 60-year-old Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Nguyệt, who owns five bat cages in Mỹ Đông commune in Tháp Mười district, in Đồng Tháp province.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, guano farming carried on.

“I’ve heard rumors saying bats caused the outbreak, but how can bats in the sky affect us?” asked a guano farmer in Tháp Mười, who wished to speak anonymously.

“Bat guano isn’t as harmful as chemical fertilizers or pesticides, they just smell a bit funky,” she added.

Delta guano farmers see bats as benign animals and a symbol of good fortune. Some like Nguyệt even think of them as pets. She is grateful for them, because the guano trade helped her family survive hunger after the historic flood in the Mekong Delta in 1978.

“Every time I sweep the droppings and see dead baby bats, my heart breaks,” Nguyệt said.

Guano farmers are very protective of their bats and do not allow strangers to stand near the cages, Thống says.

Transmission risks

Research says bats are special in their ability to host viruses. Their inflammation dampening mechanism and antiviral defense system allow them to carry many viruses asymptomatically. Being the only flying mammal and living in colonies of tens to millions which migrate every year, bats can spread viruses far and wide.

When transmitted to other mammals, including humans, such viruses can cause deadly infectious diseases. Bats are natural reservoirs to viruses and have caused outbreaks such as Ebola, Nipah, Marburg, SARS and MERS.

In Viet Nam, human contact with bats stretches beyond guano collecting. In 2007, a group of researchers found 34 bats tested positive to Nipah virus in areas where locals hunted, ate bat meat and drank their blood. They were exposed to bat droppings, fluid and even bitten by the mammal.

Another study in the Mekong Delta in 2013-2014 identified two coronavirus strains circulating in bats in guano collection areas.

Transmission can also occur through contact with intermediate agents, such as domestic and wild animals.

In 2018, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) collaborated with government units to collect biological samples from pigs, bats and humans in caves and guano farms. They found eight new coronaviruses and four new paramyxoviruses in biological samples from bats.

Interestingly, the eight coronaviruses were genetically close to the pathogen that causes disease in pigs, suggesting there has been transmission among pig farms.

“With the new virus strains that the research discovered in bats, up to now, there is no evidence that these viruses are capable of causing harm to human health,” Nguyễn Thị Thanh Nga, a WCS staff and a member of the research team, cautioned.

“However, with the results discovered, we cannot deny the potential risks. Therefore, all the results we discovered are shared with the authorities to have a contingency plan to respond to future diseases,” she said.

“People think that they have been doing this all their lives and nothing has happened, but in a few decades, hundreds, or even thousands of years, an epidemic could happen – that is a real risk,” said Dr Phạm Đức Phúc, Director of the Center for Public Health and Ecosystem Research at the University of Public Health (HUPH) and coordinator of the Vietnam University One Health Network (VOHUN).

One-Health approach

Aside from concerns for human health, scientists are also worried about the disease transmission risks humans have on bats.

In Hữu Lũng, the bat population is already suffering due to illegal poaching and smuggling.

“In Tân Lập, the bat population has declined by about 40% in the past 10 years,” Thống told this reporter.

In Đồng Tháp, although it is not clear whether the drop in population is due to poaching, farmers have also noticed a dramatic drop in the amount of guano collected.

Phúc says there is not yet any risk assessment of disease transmission from the guano collection practice.

“Some parties can take the lead to ease bottlenecks. For example, the Department of Animal Health can help improve the pig farming environment, the Department of Forestry can protect bat populations, while public health and epidemiology experts need to conduct research and assess how pathogens originating from wildlife can affect human health,” he suggested.

Vietnamese scientists have been calling on the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development to develop biosecurity measures to prevent disease transmission between wildlife and humans.

So far, restrictions on the practice are not a feasible solution. Both Thống and Nga say it would affect people’s livelihoods negatively.

While waiting for government regulations, scientists recommend that people participating in guano collection use personal protective equipment such as masks, gloves, boots etc to limit exposure.

In June, the Bat Specialist Group from the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) issued recommendations on hygiene standards for all bat field workers worldwide. Thống said this could be the basis for Vietnam to develop similar guidelines in the future.

At Tân Lập Cave, Thống and his colleagues, under the guidance of the IUCN Bat Specialist Group, have distributed face masks to cave managers and local guano collectors.

At the same time, the scientists have also coordinated with local authorities to install security cameras to detect and record hunting activities. They also called on local authorities to issue strict regulations, laying the groundwork for a permanent ban on bat hunting in Lạng Sơn province.

“We need to identify potential transmission interactions early, so we can be ready to respond. We don’t want to be as surprised as we were when Covid-19 happened,” said Phúc.

This article was originally published in Vietnamese on Tia Sáng magazine on August 12, 2024, translated to English using AI and edited by Mekong Eye.