AN GIANG, VIET NAM – “Profits as thin as rice leaves” is a common lament among local farmers like Trần Hữu Lượng, a 55-year-old rice farmer from Thoại Sơn District, An Giang Province.

After 40 years of rice farming, Lượng’s life remains deeply tied to his fields, but all he has is a bare, 100-square-meter house with no valuables.

“There are years when the revenues from rice cultivation barely cover the costs of fertilizers and pesticides; while some years yield modest profits, others result in severe losses,” Lượng, a thin man with a tan, recounted.

What Lượng describes stands in sharp contrast to media reports highlighting high rice yields from An Giang, a province located within two primary rice-growing areas in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta (VMD). While yields can reach an impressive 5-6 tons per hectare, with some areas exceeding 7 tons per hectare—nearly double that of India and Thailand, the world’s top two rice exporters—beneath these numbers lies a different story.

Lượng relies heavily on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, which account for almost half of his production costs. Lượng earns only 1,000 VND (approximately US$ 0.04) per kilogram of rice, despite his contribution to some of the highest rice yields globally. Looking at the entire rice production value chain, farmers endure the most hardship but receive the smallest share of value. They obtain only 4 to 17% of the price paid by consumers, depending on the rice quality and market conditions.

Data: An Giang Department of Finance, 2021. Graphic: Thu Quỳnh

Lượng also relies on loans from supply agents to buy seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides, which he repays after each harvest before acquiring new loans. Even in seasons of abundant harvests and favorable prices, farmers like Lượng only earn 15-20 million VND (US$611 – 815) per hectare for a 100-day crop cycle after deducting input costs.

Lượng explains that this amount is not profit but rather the equivalent of wages for labor in the paddy field.

Working from dawn to dusk, both Lượng and his wife earn a miserably low income of just 150,000-200,000 VND per day (US$ 7-9)—barely enough to stay above the poverty line. The situation is worse for families renting land, as rental costs further increase production costs, pushing household incomes below the poverty threshold.

Lượng’s situation is common across the VMD. Despite being part of a billion-dollar rice commodity chain, farmers operate on fragmented plots averaging less than 1.5 hectares per household and receive minimal profits.

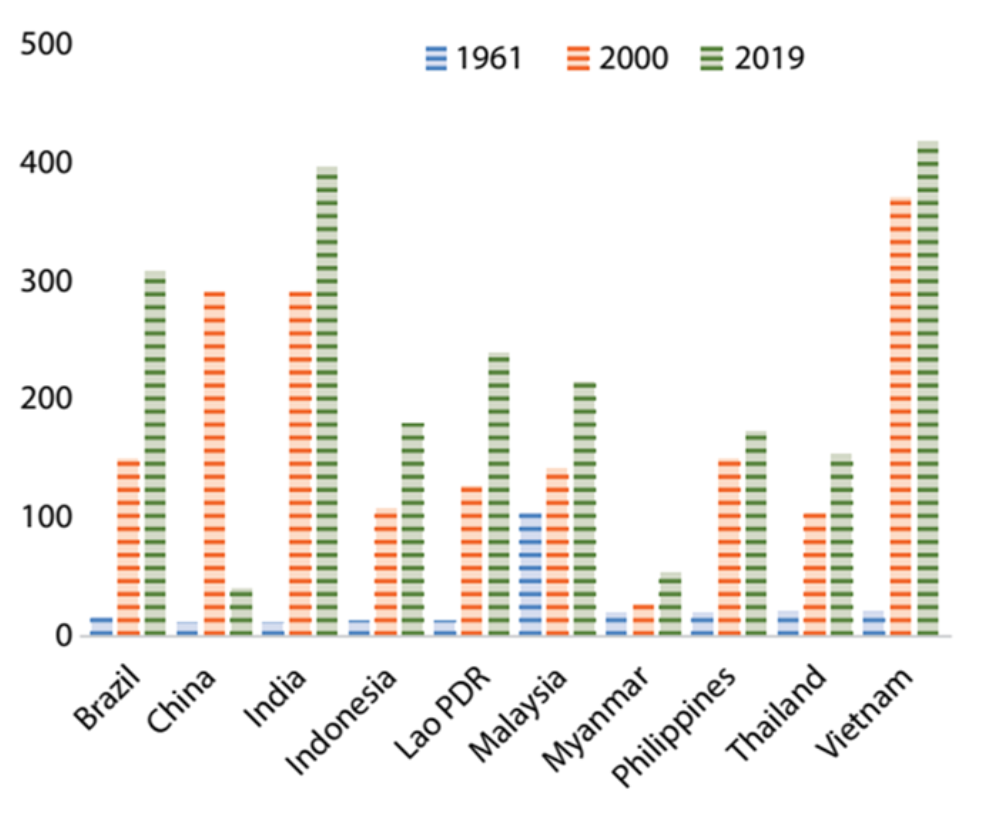

Examining the cost structure of rice production reveals that the majority of profits are made by fertilizer and pesticide manufacturers. Excluding other types of fertilizers, the quantity of macronutrients—nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium (NPK)—alone applied to fields exceeds 400 kg per hectare. When accounting for all types of chemical fertilizers, the total amount used per crop is around 550 kg per hectare. This is twice as many macronutrients as Vietnam’s next-door neighbor in the Mekong Delta, Thailand.

The extensive use of fertilizers and pesticides across three rice crops was not coincidental. For centuries, traditional farming in the region consisted of just one rice crop and one flood season allowing the soil to rest while farmers relied on fishing during the floods.

A legacy of overexploitation

The post-Vietnam War hunger crisis changed the land, and particularly soil, in the delta, compelling farmers to abandon their millennial agricultural practices.

Between the late 1970s and 1980s, both the government and local people undertook efforts to control nature by constructing a system of canals and closed dikes in Long Xuyên Quadrangle and Plain of Reeds. This infrastructure helped wash away acid-sulfate soils, prevent saline water intrusion, reduce dependency on natural conditions and facilitate multiple cropping by diverting floodwaters away from rice cultivation areas.

This phase marked the beginning of the controlling nature era, expanding the rice cultivation area in the VMD to nearly 1.5 million hectares. When accounting for all three crops per year, the total cultivated area reaches nearly 4 million hectares, which is equivalent to the entirety of the VMD.

The achievements of rice breeding research and the “Green Revolution” (the shorthand name for post-WWII agricultural shifts), not only in Vietnam but across the developing world, introduced high-yield, short-duration rice varieties that enabled farmers to shift from cultivating long-duration indigenous varieties (5-6 months per crop) to faster cycles of just three months per crop.

Although initially resistant to increasing the number of crops—some households even boiled rice seeds before sowing them in protest—farmers who were accustomed to the rhythm of one rice crop and one flood season with abundant fish eventually gave in to such varieties, one of which is called Thần nông (the Vietnamese deity who blesses rice farming).

Nguyễn Minh Nhị, the former Chairman of An Giang Province, actively led the land reclamation movement, dug freshwater canals and constructed flood-prevention dikes over ten years, transforming “long-dormant, poor lands” into valuable assets.

Reflecting on this period, he recalled, “I was deeply involved in the movement to reclaim land and increase rice production. Never in my life had I felt so useful.”

Thoại Sơn, where Lượng lives, was one of the first areas to build flood-prevention dikes to increase rice cropping. Similarly, Đồng Tháp province’s authorities in neighboring An Giang also hastily constructed flood-prevention dikes to expand cropping and address wetlands and acid-sulfate soils.

However, the accomplishments of farmers in the VMD, architects of one of the world’s most productive rice-growing regions, lasted only a decade. “Back then, we hardly used fertilizers or pesticides,” Lượng recounted.

The cost of controlling nature

The consequences of dikes and intensive farming are now gradually emerging. The once fertile topsoil, previously enriched by nutrient-rich floodwaters from the Mekong River, has been progressively depleted after 30 to 40 rice harvests. The dikes, originally designed to protect farmland, have inadvertently blocked the sediment that used to nourish the rice paddies.

“This free source of fertilizer meant local farmers could operate highly productive rice cultivation with lower input costs due to lower fertilizer requirements,” explained Alexander D. Chapman from the University of Southampton in the UK, who researches the nutritional value of the floodwaters.

These tiny particles of sediment, which deposit approximately 2.5 cm of nutrient-rich soil on the fields annually, provided essential nutrients for rice seedlings. According to Chapman’s study, the sediment in An Giang alone was valued at around US$ 15 million per year, and some estimates suggest that it could replace up to 50% of the fertilizers needed by rice plants.

“Farmers are more vulnerable to fluctuations in the market price of fertilizers, which they rely on to replace the natural sediments,” he noted.

By the late 1990s, due to the lack of this free fertilizer, the application of costly NPK fertilizers on rice had risen to 180 kg per hectare, 30-200% higher than the average volume applied in East Asia and the Pacific (almost 150 kg per ha), and throughout the developing world (90 kg per ha).

Consequently, Vietnamese rice farmers and their crops have become increasingly dependent on chemical fertilizers. Despite warnings about the necessity for Vietnam to avoid the historical experience of China, where excessive chemical fertilizer use has resulted in soil degradation and severe water pollution, the country failed to heed such a cautionary tale.

Research conducted by Trần Đức Dũng from Wageningen University in the Netherlands revealed that in terms of profitability in the short term, three-crop rice farming systems initially yielded 57% higher profits than two-crop systems. However, after 15 years, farmers growing three crops earned only 6% more than those growing two crops, despite the significantly increased labor inputs throughout the year.

The higher production costs were mainly due to an increase in the use of fertilizers and pesticides, which were needed to compensate for soil nutrient depletion, the loss of soil ecosystem rest periods and the absence of floodwaters that previously helped mitigate harmful soil pathogens.

By 2005, many farmers in the delta continued to pursue the dream of abnormally high productivity. Minh Nhị began to notice that yields were actually declining before he retired.

“Just a rough calculation showed that fields planted with three crops were experiencing reduced profit,” he recalls.

Nhị is affectionately referred to as Nhị tam nông (translation: Nhị of the three pillars of rural development; agriculture, farmers, and rural areas) due to his innovative and groundbreaking ideas during the Đổi mới era (1986-1990). This period transformed the landscape of agriculture, farmers and rural areas after the legacy of the Vietnam War. Building on his reputation and dedication as a person from a long line of farmers, and having “grown up drinking acid-sulfate water” (referring to the acid-sulfate soils in his region), Nhị wrote a nota bene paper urging a reassessment of rice productivity.

The vicious cycle of fertilizer and pesticide overuse

By the time other farmers also noticed this pattern, it was too late to end the goal of exponential productivity. The dream of achieving billion-dollar rice exports, which brought significant revenue to Vietnam, had set the entire delta in motion. Intensive three-crop rice farming did not just remain where it originated; it spread across other rice-growing provinces in the VMD.

“The drop in productivity was not immediately apparent,” noted Associate Professor Trần Kim Tính from Cần Thơ University’s College of Agriculture.

This observation may explain why officials and farmers in other provinces chose to follow An Giang’s lead. On the surface, the impressive yields and output of the VMD’s third rice crop showed no signs of trouble.

“Soil degradation leads to reduced productivity, but farmers compensate by increasing fertilizer use to maintain yields, resulting in profit losses rather than yield decline,” said Trần Kim Tính.

“We also observed how farmers in An Giang were growing rice to learn from them,” said Vũ Quốc Hiền from Long Phú District, Sóc Trăng.

In the early 2000s, multi-crop agricultural production during the dry season was made possible following the implementation of a salinity prevention project. This included the construction of sea dikes, saltwater intrusion prevention gates and pump stations, which allowed farmers in Long Phú and surrounding areas to experiment with three-crop rice farming.

At that time, Hiền didn’t foresee that Lượng’s plight would soon befall him. It appears that no one realized that exploiting floodplain areas in the Long Xuyên Quadrangle and Plain of Reeds, which used to cover more than half of the total delta area during past wet seasons, would lead to another disaster for rice cultivation.

“Back when we were growing only two crops, the yield was great, a ton per plot [1300 m2], with the lowest yield being at least 800 kg per plot,” Hiền recalled.

The reason for this was a fallow period observed by farmers between November and April of the subsequent year, which allowed the land to rest. During fallow, organic matter from rice straw accumulated, soil microorganisms had time to decompose the resulting organic material and the soil was exposed to natural elements, which helped control diseases.

However, since Hiền started growing the third crop, like all other farmers here, he has had to up his fertilizer use. Based on what other farmers throughout the delta told Tia Sáng, it seems that the fate of small-scale farmers through the delta does not differ much.

The cycle of fertilizer use has become unwieldy in the VMD, driven by multiple factors that have caused rice paddies to lose soil fertility. Scientific research has confirmed this. Experiments conducted in areas with three-crop farming showed that rice yields, which initially reached six tons per hectare, dropped to 4.4 tons per hectare after seven years.

Trần Kim Tính, after surveying thousands of sites, noted nutrient depletion and farmers have only replenished a few components of soil health, primarily NPK, forcing plants to extract essential elements from degraded soil.

Over time, the heavy use of chemical fertilizers harms the earth, making it more acidic (lowering soil pH) and limiting the nutrients available for rice plants. Soil degradation is evident in three-crop farming systems across the rice belt region. One study indicated that in the triple-rice cropping system, the loss of topsoil in rice fields has led to an 85% decrease in organic matter compared to soil that still retains its topsoil. Available nitrogen has dropped by 30%, available phosphorus has decreased by 56% and soil structure stability has diminished by 36%.

As a result, the physical properties of the VMD’s soil are adversely affected, causing it to harden and exhibit less water retention capacity, which prevents the roots of rice plants from penetrating deeply and accessing essential nutrients.

“When the root system fails to develop properly, fertilizer efficiency drops significantly, leading farmers to continuously increase their application,” Tính noted.

The consequences of relying on chemical fertilizers, often referred to as “fast food” for crops, extend beyond mere nutrient depletion. According to Đỗ Thị Xuân from Cần Thơ University, a researcher specializing in soil microbiology in the VMD, this practice also disrupts the balance of the soil microbial community.

Microorganisms, particularly nitrogen-fixing bacteria and fungi, play a vital role in nutrient synthesis, such as making phosphorus soluble or fulfilling nearly 40% of the nutritional needs of crops during periods of nutrient deficiency. However, rice paddy monocultures and excessive chemical use have reduced these beneficial microbial groups, leaving behind “opportunistic” microorganisms that cannot effectively synthesize or decompose essential nutrients. Consequently, rice plants become increasingly dependent on chemical fertilizers in this negative feedback loop.

Farmers like Hiền and Lượng may not fully understand the specific mechanisms of soil degradation, but they have observed that intensive and prolonged monoculture rice farming exacerbates pest outbreaks. In reality, pests persist in the soil for years, while only a few microbial groups can utilize available nutrients, including potential pathogens like fungi and bacteria.

This situation has, in turn, led to another serious problem in the VMD: pesticide overuse.

The extent of pesticide overuse is evident from data showing a dramatic increase in the average amount of pesticides used by rice farmers in the VMD from 1980 to the present. A report from International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) and An Giang University indicates that pesticide use has risen nearly eight to nine times since 1981. Specifically, in intensive-yield rice fields in An Giang, the average use of active ingredients is almost three times higher than the global average.

By around 2000, surveys estimated that rice farmers were using up to 64 separate pesticide chemicals. Until recently, despite Vietnam’s efforts to implement integrated pest management programs, broad surveys still reveal that approximately 95% of farmers in the VMD overuse pesticides in both rice and fruit farming systems.

Farmers don’t dare neglect even a single pesticide application, as profit margins are exceedingly narrow and any risk to the rice crop could lead to significant losses.

“Regardless of how costly the pesticide may be, we still have to buy it,” Lượng said as he explained numerous threats to a successful crop from snails, spiders, brown planthoppers (Fulgoromorpha insects), weeds (including “weedy” or “red” rice), as well as plant diseases such as leaf blight, sheath blight and grain sterility. These issues can result in price deductions by traders for even very minor imperfections.

Yet most pesticides aren’t absorbed by the crops themselves—less than 1% are used effectively. The rest of the applications pollute soil, water and air.

The toxic chemicals in pesticides adversely affect soil ecosystems by eliminating beneficial arthropods, earthworms, fungi, bacteria, protozoa and other organisms that contribute to organic matter decomposition, pest control and soil structure. The degradation, in turn, compels farmers to increase their use of chemical fertilizers.

Additionally, the continuous application of pesticides has led to resistance in pest species. For instance, brown planthoppers, the most serious insect pest in the VMD over the past 40 years, have repeatedly caused devastating outbreaks. Pesticide-resistant planthoppers have become a significant concern for farmers, who now need to mix two to three types of pesticides in one application to control them, as recounted by both Lượng and Hiền.

“Pests can reappear within a week,” Hiền said, necessitating further treatments. A test even showed that the current pesticide dosages required for effective control of planthoppers are over a hundred times higher than they once were.

The role of the vanishing floodplains

Given the years of intensive land exploitation, is there hope for soil recovery and reduced production costs for farmers? The answer lies in time and patience.

“It takes 10 to 20 years to restore soil fertility; it cannot be measured in just a few years,” said Trần Kim Tính.

The key is to leach out toxins and replenish soil organic nutrients. “A few years is insignificant; it requires consistent application of organic matter over a span of 20 years,” he added.

To leach out toxins and replenish soil organic nutrients, the challenge of soil restoration reverts to Vietnam’s engineering origins in the delta: floodwaters and dike systems.

Lượng, a farmer who has been cultivating rice for nearly 40 years, and Minh Nhị, the author of dike system and the third rice crop, describe up to 30 years of rice cultivation without seasonal flooding as “lack of floods” or “flood deprivation.” They explain that floods not only bring sediment but also facilitate the removal of residual toxins from the soil. Floodwaters inundate fields for three to four months to kill weeds and pathogens while providing a source of fish and shrimp.

“For many years, locals and scientists have debated the concept of ‘managed flooding’ in various parts of the VMD, aiming to restore sediments and nutrients to the floodplain and clear out pests,” noted Chapman, the British scientist.

Reopening the floodgates to let floods return to rice-growing areas is not only beneficial for regions like the Plain of Reeds and the Long Xuyên Quadrangle, but also has profound implications for downstream areas of the Mekong River—a realization that only emerges after experiencing the consequences of losing these floodplains.

The VMD can be broadly divided into two parts: the inland delta governed by river systems, including the Plain of Reeds and Long Xuyên Quadrangle, and the outer regions heavily influenced by the sea. These floodplains function as natural sponges, regulating floodwaters by absorbing excess water during floods and releasing it back into the main channels during the dry season. Consequently, when these water-absorbing sponges are replaced by irrigated rice fields, it results in more severe water shortages during the dry season and exacerbates flooding and saltwater intrusion during the wet season.

Land use change in the VMD from 2000 to 2020.Source: Vu et al. 2022. Land use change in the VMD from 2000 to 2020.Source: Vu et al. 2022. |  Maximum flood extension in the VMD from 2000 to 2020. Source: Vu et al. 2022. Maximum flood extension in the VMD from 2000 to 2020. Source: Vu et al. 2022. |

Overall, the VMD has lost nearly all of its swamp ecosystems, which once played a crucial role in preventing saltwater intrusion and groundwater recharge during the dry season.

Today, less than 2% of the original 4 million hectares of the VMD currently remains as primary swamp ecosystem according to a 2016 article. Both drought and saltwater intrusion underscore that the critical importance of water for the VMD, where 64% of the land is used for agriculture, with rice farming accounting for 80% of that area.

The challenges faced by farmers in distant regions such as An Giang, where the Mekong River enters Vietnam, and Sóc Trăng, where the river flows into the sea, share a deeper connection. Retaining floodplains in provinces like An Giang can help regulate fresh water during the dry season for coastal provinces. It turns out that intensive three-crop rice farming has not only trapped farmers like Lượng in An Giang, but also unwittingly made Hiền’s situation more challenging as well.

In Sóc Trăng, Hiền, who was unaware of the recent scientific discussions on the role of floodplains areas, knows that triple-cropped rice fields now suffer from increased salinity.

In 2016, when he boldly rented a large parcel for large-scale rice cultivation, he expected a profit. However, he faced severe losses due to unprecedented salinity levels, which rendered even drinking water scarce and contributed to what was described as the worst drought and salinity crisis in Vietnam for in a century.

“With 80 hectares, we only harvested six bags of rice, losing over 100 million VND (US$4,000). The fear remains vivid in our minds,” his wife recounted despondently.

This loss was part of the 245,000 hectares of rice fields (the size of a large city) that were wiped out in the VMD, accounting for one fifth of the rice cultivation area in the winter-spring period of 2015-16, and more than one third of the rice cultivation area for the winter-spring crop of the coastal provinces of the region. This destruction accounted for 90% of the agricultural damage and prompted Vietnam to seek international humanitarian aid that year.

Recently, the governments of the VMD provinces hope to return to a more “nature-friendly” approach by reintroducing seasonal flooding, initially by allowing fields to rest one season after three years of cultivation, or alternatively, for one season after two years of cultivation. This strategy is intended as a measure to address some of the prevailing issues.

Dilemma of the delta and the farmer

”Ultimately, we still can’t release the floods. For 30 years, we haven’t been able to,” said Lượng.

In the Long Xuyên Quadrangle and Plain of Reeds, there are not only rice farmers but also those growing vegetables and fruit trees. It is impossible to release floodwaters while balancing the interests of two groups whose cropping patterns and water demands differ so greatly.

Seven years ago, when the authorities in Thoại Sơn advocated for flood releases, rice farmers agreed to the idea due to the depressed rice prices. Conversely, cucumber and watermelon growers resisted the initiative.

Two years later, when the authorities attempted to advocate for flood releases again, rice farmers rejected, as rice prices had risen and growing rice seemed more profitable than in previous years. Despite the fact that fragmented rice farming barely provides subsistence, it still offers a modest income.

“It’s a challenging endeavor, but what alternative do we have?” Lượng said, gazing at his newly sown fields.

In Sóc Trăng, Hiền and other local farmers have yet to abandon the third crop even after a historic salinity crisis, despite being acutely aware of the risks associated with cultivating a third rice crop.

This year, salinity affected the newly sown paddies, which were only 20 days old, necessitating reseeding by Hiền and farmers in Long Phú. “We keep monitoring and pumping water when fresh water from An Giang arrives,” Hiền said.

Just like Lượng, Hiền and his family, including his two school-age children, depend solely on this paddy.

“The economic and environmental advantages of managed flooding are not enough to persuade farmers to abandon a rice crop. Without rice, what alternative livelihoods can sustain them during months of scarcity?” Trần Đức Dũng noted after assessing solutions to the impacts of flood protection and third rice crops in both the Plain of Reeds and the Long Xuyên Quadrangle.

It turns out that the construction of flood protection systems and the intensive cultivation of two to three rice crops per year have fundamentally restructured the roughly 7,000-year-old delta, transforming farmers’ behaviors in ways that make returning to past practices impossible.

Even now, Minh Nhị, the architect of flood protection and a third rice crop in An Giang, failed to foresee one critical issue – “flooding without benefiting from floods.”

Nguyễn Văn Tắc, head of the Vĩnh Bình Cooperative in Châu Thành, An Giang, reported that the once-abundant floods no longer arrive. The floods now only reach one third of their previous depth, bringing only water without sediment or fish.

He and other local farmers understand that upstream hydropower dams have blocked sediment and fish, with scientific estimates showing that Mekong River sediment has decreased by 74%, and future projections suggest almost no sediment will flow to the delta.

The macro decisions made upstream have left downstream farmers in a state of desperation as they and local authorities struggle to tackle the consequences of past decisions.

After 40 years of Vietnam’s Đổi mới, the Green Revolution in the rice fields of the VMD has essentially produced a trade-off, in which soil and water resources are sacrificed for productivity. With impoverished soil and exhausted farmers, the pressing question remains: Is there any way to alter the fate of the farmers and their soils?

The future of rice, soil and farming

Looking at the input factors for rice production, half of the costs are related to soil. The more paddy soils degrade, the higher the price is paid. Thus, optimizing rice production depends on soil quality.

In response, the Vietnamese government has initiated the “One Million Hectares of High-Quality Rice” program, aimed at reducing input costs, reducing farmers’ difficulties and protecting the soil.

The expectation is that this macro-level change across the entire VMD will begin with micro-level adjustments at the smallest and most vulnerable links in the commodity chain: in rice paddies and with farmers.

These farmers are now required to reduce their use of fertilizers and pesticides by approximately a quarter and cut input costs by 10-15%. This is in line with the recommendations of scientists such as Trần Kim Tính and Đỗ Thị Xuân, who emphasize the need for organic fertilizers and the adoption of regenerative farming techniques.

This transformation will require several technical steps, such as using alternate wetting and drying irrigation to promote deeper root growth and stronger plants, applying fertilizers below the soil surface to prevent runoff and reducing seeding density.

Each of these steps must be implemented carefully. For example, water management in wetting and drying irrigation requires that “farmers must not drain the fields by removing water, as this can be extremely harmful and can rapidly acidify the soil,” explains Tính. According to Tính, farmers should therefore carefully estimate the amount of water and the amount of irrigation to ensure their fields dry out at the appropriate time.

The cooperative model could be a solution for transformation in the VMD as well, which has the capacity to become a beacon for spreading such production models into “large fields,” thereby overcoming staggered production that leads to high input costs while demonstrating the effectiveness of new farming techniques. These are factors that could help minimize risks for rice farmers.

Given the new technical demands in organization, this transformation is being piloted at key cooperatives like the Vĩnh Bình Cooperative, which has stood out for its 10 years of experience.

As Vĩnh Bình’s leader, Tắc, a knowledgeable and experienced figure, has been particularly recognized as a progressive farmer. He has actively participated in various training programs that cover both production techniques and cooperative management under a business model. Tắc indicates that Vĩnh Bình is currently transforming 15 hectares as a part of the “One Million Hectares” program, with plans to expand to 50 hectares in the future.

However, large-scale field models and cooperative production remain key bottlenecks to innovation in rice cultivation and, as a result, in the restoration of soil health.

Despite policies and high expectations, the area of rice cultivated under this model currently accounts for only 6.6% of the total rice area in the country. Moreover, cooperatives, which are the core units for linking farmers to large-scale production, lack the capacity to manage the risks associated with the entire rice commodity chain.

The leaders of these large-scale production models must be trained and capable of running a real business—a significant challenge given that 90% of agricultural farmers in Vietnam have not undergone formal training. As a result, effective cooperatives like Vĩnh Bình are rare. These cooperatives help members by reducing agricultural input costs by up to 20%, providing new technical guidance and stabilizing rice purchasing prices.

Having observed the failures of other cooperatives that have come close to bankrupt due to large-scale production without proper risk management, Tắc remains reluctant to organize joint production activities or sign exclusive product purchase agreements with any single business.

Instead, he operates the cooperative on a “zero-fund” basis-simply connecting cooperative members to buy agricultural inputs together and sell rice collectively to gain bargaining power with agricultural supply companies and traders, avoiding being squeezed on price. Despite this, the demand of networking keeps him constantly busy with building relationships and negotiating with 112 farming households and agricultural input businesses.

Meanwhile, vulnerability of smallholder farmers requires careful consideration, said both Chapman and Dũng. With minimal profit margins and no savings, even one wrong decision resulting in a failed crop can leave farmers in debt for a long time, prompting them to overuse fertilizers and pesticides to accelerate higher yields.

Faced with a new rice farming project that requires significant reductions in inputs, smallholders like Lượng and Hiền hesitate to make the change.

“Increasing inputs hasn’t even been effective, let alone in reducing them,” Lượng said.

Both of them are waiting to see successful real-world examples. “If I try [to reduce fertilizer and pesticide use] and it goes wrong, I’ll have to leave home and work as a laborer in Bình Dương [an industrial province],” Lượng explained.

This story was lightly edited for length and clarity. The original story can be found here in Vietnamese and here in English.