Published on December 2, 2024

Larb Ngua Dip, a meal of raw beef drenched in blood, lime, chili and herbs, is not for the faint of heart, but it is a fresh and tangy delight for its fans in rural Laos.

Locals never expected that this popular dish could leave them with uncontrollable vomiting and black skin lesions, as experienced by some residents in Champasak and Salavan, provinces bordering Thailand and Vietnam.

The symptoms were first reported in a few patients admitted to hospitals in March, with cases surging to 121 by April, according to a local news report.

The beef they consumed was contaminated with Bacillus anthracis, the germ that causes anthrax, locally known as Payad Kai Lued Dam (black fever). The bacterium is known to spread from cattle to humans through contact with its spores in the soil, or through the consumption of infected meat.

The exact source of the infected cattle remains unclear, but the outbreak prompted Thai, Lao and Vietnamese authorities to heighten surveillance on transboundary cattle movement and disease control.

Laos’ Department of Communicable Diseases advised the public to be cautious with raw beef consumption, while restaurants were hesitant to serve such dishes.

Although anthrax has been largely contained in the Mekong region over the past two decades through vaccinations, it continues to be reported in some countryside villages near the border.

Severe cattle diseases like lumpy skin disease, which was never detected in the region before October 2020, have also emerged and affected more than 1.75 million cattle in a year, posing a serious risk to food security.

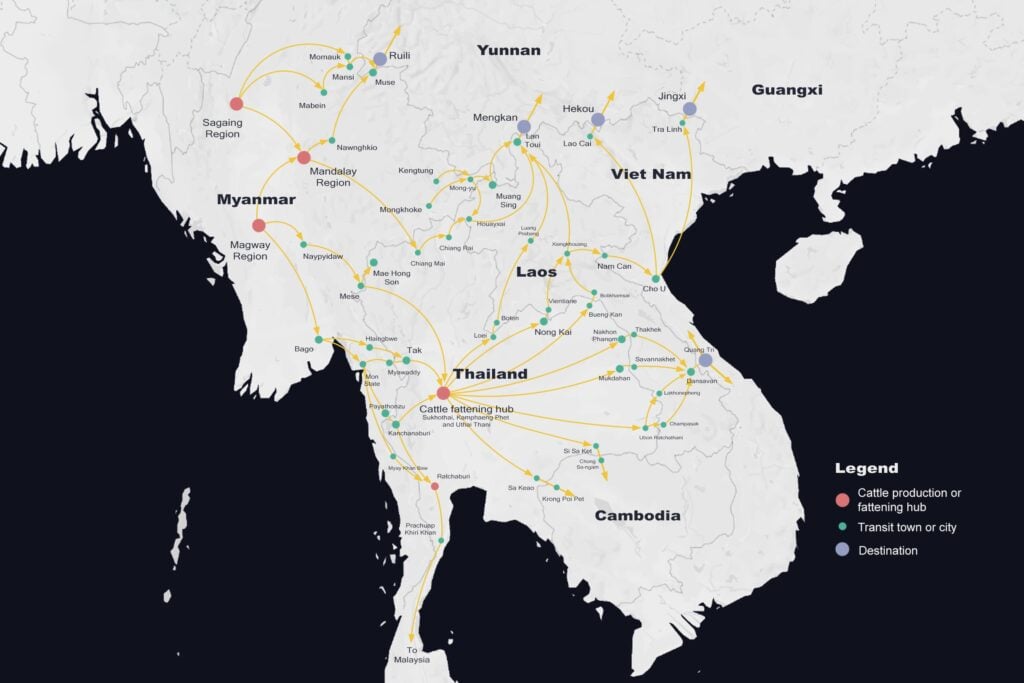

Such outbreaks are likely to continue and rise as the decades-old illegal cattle trade expands to meet the growing demand for beef in China’s southern Yunnan and Guangxi provinces as well as in Viet Nam.

Beef holds a special place in the local cuisines of the Mekong region countries. Residents in China’s Yunnan province enjoy niu pahu, an aromatic braised beef and intestines soup. Rural Thais and Laos savor soi ju, raw beef and offal dipped in a spicy sauce, while the Vietnamese love their comfort food phở bò for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

On top of traditional dishes, all-you-can-eat beef hotpots at affordable prices have been trending among the region’s middle-class urbanites.

China is the world’s second-largest beef consumer by total volume after the United States, with around 10.5 million tons consumed in 2023.

The 2024 agriculture outlook, published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), projects China’s beef consumption per capita to rise by 10% by 2031 after having risen 50% in the last decade.

Viet Nam consumes less than 10% of China’s total volume, yet its consumption per capita was estimated at 8.5 kilograms per year in 2022, double that of China and six times higher than Thailand.

Despite rising consumption, Viet Nam’s cattle herds only meet less than half of domestic demand, while China’s beef production has stagnated due to urbanization, forage degradation and rising labor costs.

This gap, coupled with the demand for cheaper meat, has led to a reliance on the import of live cattle from other Mekong countries – through both formal and illegal channels, with the latter run by a vast network of farmers, brokers and traders.

Often with the help of border patrols and local authorities, many smugglers purposefully evade measures to control transboundary animal diseases at the cost of public health and the millions of farmers’ livelihoods that depend on the cattle trade.

A presentation by a researcher from the Yunnan Animal Science and Veterinary Institute, published by the World Organisation for Animal Health in April, reveals that 220,000 cattle are smuggled annually across the Yunnan border, which connets to Myanmar, Laos and Viet Nam.

Incentives for smuggling have increased since the Covid-19 pandemic and lumpy skin disease outbreaks in Asia, which peaked between 2020 and 2022, local traders told Mekong Eye.

These twin crises prompted China and the Mekong countries to restrict cross-border animal movement, leading farmers and traders to increase their dependency on smuggling.

Meanwhile Myanmar, the region’s biggest cattle supplier, had a military coup in 2021 that led to escalated conflicts across the country, forcing many traders to rely on smuggling networks that could secure safe passage to the borders.

The resulting civil war after the coup also led to a sharp decline in government support for animal disease control and vaccination programs, as resources were diverted to combat ethnic armed groups and suppress anti-regime movements.

This raised the risk that smuggled cattle could carry diseases into new territories.

“We do not ask the origins of the animals here,” said a Chinese cattle trader at Mangshi, a major livestock market in Yunnan near the Myanmar border. “It’s not necessary to worry about disease. If the cattle are sick, they would not be able to journey that far.”

However, this is far from the truth.

“Cattle may only show signs of disease during transportation,” said Dr Therdsak Yano, a professor at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Thailand’s northern Chiang Mai University, who has studied the cross-border movement of cattle in the Mekong region.

“When they are stressed, exhausted and hungry, their immunity drops. Symptoms appear, and they can spread a virus along the way.”

MYANMAR: Escalating war drives cattle smuggling

A farmer feeds cows in Myanmar’s central Magway region, where cattle serve as a primary source of income and labor for the local community. PHOTO: DVB

Screeching noises broke the calm of a chilly morning at the open livestock market in Mangshi, a town in China’s southern Yunnan province near the Myanmar border. Trucks had arrived, filled with cattle and buffaloes.

The animals were taken off the vehicles and led to an open, dusty ground. More than 100 head of live cattle were there, awaiting inspection by eager buyers.

These animals would soon be taken to other local markets for resale, to cattle fattening farms or sent to slaughterhouses to meet the growing demand for meat from Chinese consumers.

For decades, traders at the Myanmar-China border have seized the opportunity created by the gap between cattle supply and demand.

Adi is one of those. He visits a hotel lobby once a week to use the internet in Myitkyina, the capital city of Myanmar’s northernmost Kachin state.

Since the civil war approached the city’s outskirts in September, his home internet had been cut off for several months. Hotels were one of the few places that still provided internet access.

He sends videos of live cattle to Chinese merchants on the other side of the border via China’s most popular messaging app, WeChat.

After the buyers have inspected the age and health of the animals through the videos, if they decide to buy them, they transfer a deposit to Adi. The remaining payment is made during the handover.

Adi then immediately contacts a logistics company that smuggles live cattle into China, taking advantage of the rugged border terrain.

Walking the cattle across the border for two days is part of the plan, as well as bribing border officials and armed forces to secure safe passage.

Due to the intensifying fighting between Myanmar’s military and ethnic armed groups, Adi has lost his home and farmland and now lives in an internally displaced persons camp.

Acting as a broker in the cattle smuggling trade is his only means of earning a livelihood. Many villagers there opt for the same path for survival.

This lucrative business capitalizes on Myanmar’s large cattle supply and low domestic consumption, influenced by religious practices that encourage abstaining from beef.

According to the country’s National Livestock Baseline Survey 2018, approximately 9.6 million cattle are raised by 2.2 million farmers.

The central dry zone, covering the Mandalay, Sagaing and Magway regions, holds more than half of the national cattle population and has been the major cattle production hub.

A study published by the Torino World Affairs Institute estimated that in 2017, about 4,000 cattle were smuggled across the Myanmar-China border daily, with only 1,000 entering legally. A presentation by a research fellow in works anilam health organization shows 220,000 heads were smuggled at Yunna border alone.

Other research in 2018, conducted by scholars at the University of Queensland, pointed out that about 150,000 Myanmar cattle indirectly enter China through Thailand, Laos and Viet Nam annually.

To curb smuggling and transboundary animal diseases, bilateral trade negotiations between Myanmar and China have been taking place since 2017, leading to the signing of a protocol on cattle quarantine and disease control in January 2020.

The plan was put on hold due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which led to 1,012 days of border closures and left more than 15,000 live cattle stranded at the border.

China also built a 500-kilometer barbed wire fence along the border to prevent the spread of coronavirus from Myanmar, simultaneously blocking the smuggling of migrants related to cyber scam rings.

This measure had serious implications for the cattle trade, which now faces increased restrictions. Although the border eventually reopened in January 2023, the trade was then damaged by the war after the military coup two years earlier.

Heavy fighting broke out after the Three Brotherhood Alliance – a coalition of ethnic armed groups including the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army and the Arakan Army – launched Operation 1027 on October 27 last year to seize control of the area from the military along northern Myanmar’s border with China.

Clashes also erupted along the main cattle transportation route to Muse – Myanmar’s export point to China’s Ruili town in Yunnan province. Some trucks were attacked and cattle in transit were reportedly killed.

Transportation now takes longer due to logistical disruptions, while inflation has driven up logistical costs.

Despite the conflict making the cattle trade a riskier business, it has also helped sustain smuggling, as both the military and ethnic armed groups benefit by collecting bribes – or what they call “taxes” or “gate fees” – from traders to guarantee the safe delivery of their animals to the border.

But unlike an official tax system, the profits from these fees are usually unrecorded. It is unclear where the money goes, though it is believed it goes to partially fund the ongoing civil war and other illicit activities.

One broker from the Magway region, one of the major cattle production hubs, explained in anonymity that he typically pays about 3 million kyats (US$1,400) per military checkpoint to move between 100 and 150 heads of cattle from inland Myanmar to the border – an amount that maximizes profits by reducing the number of trips.

Some military checkpoints request fees amounting to about 10% of the total value of the cattle, although sometimes they demand more.

He also has to pay ethnic armed groups – at least three different groups on each route, whether to the China or the Thai border. Thailand is a hub for cattle fattening that helps increase the value of them, and also a market for low-weight cheap cows coming from Myanmar.

Near the Thai border, armed groups request fees in Thai baht, with payments made in lump sums for each trip, ranging from between 10,000 and 20,000 baht ($300 and $600). Close to China, armed groups require fees of about $5 per head of cattle.

Despite the transportation and payment at various gates, Manoj Potapohn, an economist from Chiang Mai University who co-studied the cattle trade in Myanmar, said the nature of the cattle trade was volatile with high risks and high returns.

Even with the transportation costs and gate fees, brokers gain nearly half of the price sold at China’s border – the equivalent of more than a $400 gain per head of cattle. Farmers gain $400 per head from selling to brokers, while the selling price at the border is between $1,100 and $1,400.

Although Myanmar’s cattle disease reports have not been available since the military coup, data from the World Organisation for Animal Health shows that between 2016 and 2020, the country previously reported zoonotic diseases in cattle.

These include nearly 30 cases of deadly anthrax and 116 cases of brucellosis, a bacterial disease caused by Brucella abortus. The bacteria can be transmitted to humans via direct contact or consumption of infected animals and their milk, causing flu-like symptoms

These numbers likely represent only a fraction of cases, as Myanmar’s reporting system was not well developed.

Foot-and-mouth disease is also a major concern, with more than 13,400 cases reported in the same period. Although it rarely affects humans, it has severe economic impacts due to its high contagiousness among livestock.

THAILAND: Cattle laundering

Cows are transported on a truck to a livestock market in Thailand. VIDEO: Nattakit Meesakul

One night in July, five villagers were caught in the jungle after walking 20 cows across the shallow Moei River from Myanmar into Mae Sot town in Thailand’s Tak province.

They hid in the dark, waiting for a truck to pick up the animals. Thai border patrol officers soon discovered and arrested them for illegally importing the cattle.

The villagers claimed they had been hired to transport the cows from a small village in Myanmar’s Karen State, earning about $8 per head of cattle. They did not know who was behind the smuggling operation.

The cattle, looking thin and pale, were believed to be headed towards local livestock markets or fattening farms and may have ended up being exported to Laos and Viet Nam – which are used as transit routes for cattle bound for China.

This detection of smuggled live cattle was only one of at least 23 incidents, involving 1,182 head of cattle seized in Thailand between 2022 and the first half of this year. This figure is based on local news reports and represents only a fraction of the actual total.

Thailand is an important transit country in the Mekong region’s cattle trade, with cattle moving through on their way to China.

Around 150,000 heads was legally imported into Thailand in 2022, according to Thailand’s Livestock Department, with about 1.7 million cattle recorded in the country.

Thailand exported more than 400,000 head of live cattle in the pre-Covid year, targeting Laos and Malaysia. Exports reduced by more than half after the pandemic, with Viet Nam rising as the main trading partner.

Smuggling across the 2,416-kilometer Thailand-Myanmar border mostly happens at night through natural passageways and areas without border patrols. The hotspots are provinces such as Tak, Mae Hong Son, Kanchanaburi, Prachuap Khiri Khan, Chumphon and Ranong.

According to three traders, between 10 and 20 cattle are smuggled each night during the dry season at just one location in Tak province, with many other sites active as well.

To minimize losses in the event of a seizure, traders move the cattle in small groups, which also makes it easier to transport the animals on small trucks.

When the cattle arrive in Thailand, they are mixed with local herds in a process known as “cow laundering.”

Brokers present the cattle to local livestock officers, claiming they are legitimate, but they failed to register them on time. If no suspicious signs are detected, the officers will register the cattle and issue certification.

Once legally certified, the cattle are vaccinated and receive permission to be transported. After being moved to non-border provinces, they can be given ear tags issued by the Livestock Department and can then be moved anywhere.

Other brokers confirmed this same practice occurs in Laos, Viet Nam and on the southern China border.

Myanmar cattle are often medium-sized, weighing about 200 kilograms, and typically sell for $150 to $200 per head at the Thai border livestock market, while local Thai cattle sell for four times that amount.

However, if properly fattened, the value of Myanmar cattle can increase significantly, reaching up to nearly $1,500 a head – a profit margin that drives many to risk smuggling cattle.

“It’s easy to identify smuggled cattle from Myanmar. They are smaller and thinner than locally raised cattle and are sold at much lower prices,” said Srinuan Sunthorn, a cattle farmer from Chai Prakan district in Thailand’s northern Chiang Mai province.

This implies that some officials know where the cattle come from, but turn a blind eye.

Interviews with local farmers and livestock officers revealed references to an "influential group" of individuals, including various political players, who are involved in the illegal cattle trade at the expense of both animal and human health.

“I would say only about 30 people, including those tied to politicians, largely benefit from cattle smuggling. We have called for a crackdown on illegal cattle, but these efforts have been ignored,” said a former livestock officer who worked at the northern Thai border.

This illicit activity has been raised numerous times in the Thai parliament, although no clear solutions have been proposed.

Karit Pannaim, an MP from Tak province and a member of the now-dissolved Move Forward Party, reported to the parliament that registration tags for cattle were being reused multiple times for suspected smuggled cattle in his province. Despite this, the cattle were able to pass through five checkpoints, indicating corruption within the system.

Chalermchai Sri-on, a member of the Democrat Party and a former Minister of Agriculture and Cooperatives, acknowledged the presence of "gray networks" involved in cattle smuggling.

"The influx of cheaper, illegally imported cattle has caused local prices to drop, hurting the livelihoods of Thai farmers," he said, referring to Thai cattle prices that have nearly halved over the past five years.

When contacted by a reporter, Paiboon Jaided, the Vice-President of the Thai Livestock Association, declined to comment, citing threats he received after disclosing information about cross-border cattle smuggling during a public seminar earlier this year.

VIET NAM: Hungry for beef and profits

Beef is an integral part of the local cuisine in the Mekong region. VIDEO: Nattakit Meesakul

Viet Nam faces serious cattle disease outbreaks almost every year, notably the lumpy skin disease outbreak in 2021 which killed nearly 30,000 head. Within the first six months of 2024, a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak infected more than 1,400 cattle across 13 provinces.

Human anthrax cases have been reported almost every year in the past three decades, mainly in the northern and central provinces bordered by Laos and China.

However, these threats to animal and human health are not a concern for local traders, who make handsome profits from smuggling cattle.

Like most traders, Mẫn, a 42-year-old man of Nùng ethnicity, admitted he sold sick cattle to markets, though he refused to disclose which ones.

He has traded live animals in Trà Lĩnh market in northern Cao Bằng province, bordering China, and rarely missed a market in the past six years. Operating five days per month, this market hosts hundreds of thousands of cattle that are sold annually.

As a young man, Mẫn was duped into manual labor across the border, only to return home in debt. He believes cattle smuggling was his way out of destitution.

He and and hundreds of other ethnic Mông, Nùng and Tày in Cao Bằng are part of an intricate transboundary smuggling network that supplies Viet Nam and China with cattle from the Mekong region.

They tap into the immense profits from the unfulfilled demand for beef in southern China as Viet Nam has not been able to formalize cattle exports with Beijing, while the local market is only getting bigger as Viet Nam’s appetite for beef increases.

In 2022, the country’s beef consumption per person was 8.5 kilograms per year, double that of China and six times higher than Thailand, according to the FAO.

Domestic production now only meets about half of the country’s demand. Half of Viet Nam’s beef imports are from Australia, and the rest are from countries like Thailand and the U.S.

It imported more than 220,000 head in 2022, according to UN Comtrade data, which declined from about 740,000 head in pre-Covid times.

The transnational network of cattle smuggling starts from Laos to Viet Nam, with smugglers masking the cattle’s origin by paying local residents at border villages to act as legal cattle owners, while bribing village heads and local authorities to process the paperwork.

It costs 500,000 VND ($20) per head for a certificate of origin and a certificate of quarantine, which can easily be issued by local health authorities without examination.

Then the cattle head directly to major black markets such as Đô Lương or Ú in Nghệ An province, where they are either sold for domestic consumption or continue the arduous journey across the China border.

“Everyone in this village trades cattle,” said Nam, a trader at Ú market with two decades of experience. Many of his relatives are also involved in the illegal transnational trade.

Sold cattle are then loaded onto small trucks that head 600 kilometers north. At night, they rest at fattening farms, which cost smugglers 50,000 VND per cow per night ($2).

At Trà Lĩnh market along the China border, also known as one of the final rest stops, the cattle go through another selection. The fit cattle continue on to cross the border, while the weaker ones are sold domestically.

Smugglers drive the selected cattle to a border post at dawn, passing by border stations with an approximate bribe of 300,000VND per cow ($12).

Mẫn told our reporter that at the foothills where the border can be crossed on foot. Each resident herds a female-male duo across the rugged terrain, before handing the cattle over to Chinese smugglers.

Health checkpoints are far and few. If quarantine and checkups are carried out, they can only detect symptomatic cows, ignoring those in the incubation period.

The entire journey – in which the cattle live in trucks and walk long distances – can take as little as three to four days.

According to Mẫn, many of the cattle end up being too weak to traverse the rocky hills, forcing smugglers to return them and sell them to domestic markets at a loss of at least 5 million VND ($200) per head.

In 2023, Mẫn lost nearly 600 million VND ($23,600) when nine of his cattle were confiscated on the other side of the border. But Mẫn is not bothered by the occasional loss. He recalled transporting up to 30 cattle a day last year, making a profit of 800,000 VND per head ($31).

“Some months I earn several hundred million, so losing 600 million [VND] occasionally is quite normal. In business, you have to accept the risks,” Mẫn said.

“Once the foreign cattle were unloaded, many traders immediately herded our local cattle in. The movement of cattle from one region to another has led to the spread of diseases,” said Phùng Thế Hải, the Vice-Chairman of the Association and Director of the National Livestock Breeding Center.

Additionally, he noted that many people use the same vehicles to move cattle as they do to transport their feed, which accelerates the spread of disease even further.

The Vietnamese government has mulled banning cattle from Laos, Thailand and Cambodia if disease control does not improve.

Disease burden on transit countries

Amethods for infected cattle carcasses at a government-affiliated veterinary center in Champasak Province, Laos. PHOTO: Chris Trinh

The appeal of cattle smuggling isn't only the high profit margins, but also the significant cost savings from not complying with measures for controlling transboundary animal diseases.

Through smuggling channels, the cattle bypass the need for vaccinations and quarantine, which can take up to 30 days at the Thailand-Myanmar border and up to 82 days at the border of Myanmar or Laos and China.

These include 45 days of quarantine at local farms and 30 at the center near the export country border. Animals must be kept in a confined area and killed within seven days after entering China’s border.

During this period, traders are required to pay for the cattle’s upkeep, which can cost $2 to $3 per day per head to maintain their weight before they can enter the Chinese markets.

These expenses push many traders to rely on smuggling, where they only need to pay smugglers a few dollars per head and avoid the costly waiting period. Avoiding the measures for controlling transboundary animal diseases comes with public health costs.

"About 70% of diseases that infect humans are transmitted from animals or have animals as carriers," said Dr Therdsak Yano, a veterinarian from Chiang Mai University, who has studied the cross-border movement of cattle in the Mekong region.

These diseases are zoonotic, meaning they can infect humans through direct contact, consumption of animal products or via vectors like ticks and mosquitoes.

The zoonoses transmissible from cattle to humans is limited to a smaller proportion of infections, mainly bovine TB, brucellosis, anthrax, cryptosporidiosis, rabies or salmonellosis.

Such contact can occur in various situations, including when smugglers rest cattle or buffaloes in community areas, or when traders bring infected animals to local markets.

These markets are often crowded with animals, increasing the chances of disease transmission from one animal to another, or to humans.

While anthrax has been contained in the Mekong region, some human cases have re-emerged in Laos and Myanmar, with Viet Nam reporting annual cases since the late 2000s, particularly in northern provinces near Laos.

Brucellosis, a zoonotic bacterial disease caused by Brucella abortus, is reported annually in the Mekong region. The disease can transmit to humans via animal products – raw milk and cheeses in many cases – and cause flu-like symptoms.

It is one of the most widespread zoonoses and has serious public health consequences, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), although few human cases have been reported in the Mekong region, mainly because there are few studies on this.

The World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS)'s data for 2023 is only available in Thailand, which reported 258 cattle cases.

The WHO has also monitored zoonotic tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium bovis in cattle, with reports of animal cases in Myanmar, Thailand, Viet Nam and China. Limited human cases in the Mekong region likely stem from challenges in identifying infection sources, despite tuberculosis being a major public health concern.

Anti-Microbial-Resistance (AMR) infection in animals is another major concern, which is acknowledged as an emerging infectious disease that is affecting global public health and food safety.

It is caused by the continued use of antibiotics in livestock that evolves antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which can enter the human body through meat consumption and result in illnesses that are difficult or impossible to treat with standard antibiotics.

The 2023 annual report of Thailand’s National Animal Health Bureau revealed that one-third of nearly 2,700 meat samples contained excessive antibiotic residues used to combat Salmonella, and nearly half contained those used for killing E. coli. These two bacteria can cause stomach cramps, severe diarrhea and fever.

After H5N1 bird flu was first detected in dairy cows in the United States this March, local authorities through Asia are closely monitoring cattle health.

Transboundary animal diseases do not only affect human health, but also impact food security, cause economic loss and affect the livelihoods of millions of farmers who benefit from the trade.

This impact was manifested during the Mekong region’s first outbreak of the highly contagious Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD) between 2020 and 2022, with Thailand and Viet Nam being the hardest hit.

Although it is not transmitted to humans, the disease causes severe loss of production as infected animals fall ill, with symptoms like fever and enlarged lymph nodes, and produce less milk.

Nearly 150,000 cattle in the Mekong region were infected during the peak of the outbreak in 2021, according to the data extracted from WAHIS. Around 2.6 million are considered susceptible cases, meaning there at risk of infection because of not being immunized.

One study in Thailand revealed that the total economic losses were $2,461 per affected farm, primarily due to the cost of treating infected cattle and the decline in milk production.

World Organization for Animal Health's phylogenetic analysis suggested that the LSD virus strains responsible for outbreaks in Viet Nam were similar to those found in China and Russia, while strains in Myanmar resembled those in Bangladesh and India.

This pattern indicated that the spread of the disease was strongly linked to illegal animal movement, which also explains why Thailand shut down the border to suspend formal cattle trade with Myanmar.

This trade had not resumed as of November 2024, which is one of the factors that fueled cattle smuggling to serve the demand for beef.

In addition, foot-and-mouth disease is a major concern in the Mekong region. The disease causes symptoms from fever to weight loss and a drop in milk production and often leads to the suspension of border trade whenever the outbreak occurs.

Underfunded animal health

A seller arranges medicine and vaccines for cattle at a livestock market in northern Thailand. VIDEO: Nattakit Meesakul

In the Bago region of central Myanmar, one of the major cattle suppliers, veterinarian Ko Zaw has observed a decline in animal health programs since the 2021 military coup.

The government used to provide funds to local authorities and veterinarians to raise awareness about animal diseases among farmers, deliver vaccines to farms and monitor disease outbreaks.

“The previous government’s livestock department regularly administered vaccines as part of the animal health program in our area. We could prevent cattle from diseases and treat them,” he recalled.

“Purchasing vaccines is more difficult in the current situation due to logistic disruptions. The funds are not always available.”

During the 15th meeting of the Upper Mekong Working Group on Foot and Mouth Disease Zoning and Animal Movement Management in February, Dr Toe Min Tun, the Deputy Director-General of Myanmar's livestock department, reported that his unit could provide 300,000 doses of vaccine against the disease annually.

This amount can support only a small fraction of the nearly 10 million cattle raised in the country.

He added that the government planned to produce one million doses this year through a new vaccine manufacturing facility supported by a Japanese fund. However, this project has not progressed as planned due to the ongoing conflict.

With the suspension of international donors’ support, Myanmar finds itself struggling to deal with animal diseases.

The budget allocation for the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation declined from 4% of the annual government budget in 2019 to about 0.4% and 1.3% in 2023 and 2024, respectively.

A similar trend has been observed in Laos, where the livestock sector received about 1% of the government budget this year, largely due to economic challenges driven by high inflation. Viet Nam’s agriculture and livestock sector sees less than 1% of the contribution.

Shrinking the budget led officials to save costs by minimizing animal disease surveillance and control programs.

“The responsibility now falls on the farm owners to manage the diseases themselves,” said a government veterinarian in Laos, who requested anonymity.

Another veterinarian in the country’s northeastern Xiangkhouang province expressed concern about the impact of inflation on surging prices of animal medications and vaccines, mainly imported from Thailand.

This resulted in higher costs to keep animals healthy and forced many farmers to deduct the cost by resorting to smuggling.

Thailand has been able to maintain its budget allocation for the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, which oversees the livestock sector, with a contribution of about 3% from the government’s annual budget.

With this steady flow of funds, the livestock department has been able to produce more than 100 million doses of free vaccines for animals across the country and distribute them to farmers at no cost.

These vaccines include 40 million doses for foot-and-mouth disease, targeting nine million cattle, each of which requires two doses per year. Thailand has a surplus, which is exported to Myanmar and Laos, while Vietnam has established a vaccine manufacturing hub that also exports to neighboring countries.

Despite this progress, Dr Therdsak from Chiang Mai University believes there is still room for improvement.

Thailand’s public health system has been recognized as one of the best globally, with the introduction of the Universal Coverage Scheme in 2002 and continued investment in health infrastructure from the provincial to sub-district level.

However, the investment gap remains in the area of animal health despite its importance to human health, said Dr Therdsak.

One area of under-investment is personnel, with Thailand’s district livestock departments typically having only four to five staff members, often with only one person authorized to manage outbreaks or declare epidemic zones.

A livestock officer from a district along the Thai-Myanmar border, who spoke anonymously for safety concerns, mentioned that his team of seven was responsible for monitoring transboundary animal diseases along a border stretch of more than 30 kilometers.

"What we can do is vaccinate the animals and conduct disease tests when we receive reports of cattle crossing the border illegally. But if no one informs us, there's little we can do," he explained.

With little resources, the livestock officers will randomly inspect local cattle markets, where smuggled cattle from Myanmar are present for resale to traders. If the markets are found lacking in disease control measures, they will be shut down until those measures are implemented.

LAOS: Dilemma of cattle trade formalization

Cows roam the streets of Pak Chong town in Laos's southern Champasak Province. PHOTO: Konlaphat Siri

UN Comtrade data shows that China’s cattle imports reached a value of $804 million in 2022, more than tripling over the past decade. Nearly 650,000 head of live animals legally enter the country – primarily from Australia, New Zealand and South America.

Laos has witnessed a dramatic 1,000-fold increase from 2012 to 2021 in its cattle trade value, largely serving as a transit country for livestock shipments from Thailand and Myanmar en route to China and Viet Nam.

The trade data is not available for Cambodia, but it is known by traders as a transit country.

This increase in trade has prompted China and the governments of Myanmar, Laos and Thailand to pursue cattle trade formalization in recent years.

China’s General Administration of Customs lists all these countries as foot-and-mouth disease epidemic areas, meaning the import and export of live animals are completely prohibited except for a few areas that agreed to comply with China’s animal health protocol.

While Myanmar suffered a military coup in June 2021, Laos announced its target to send 500,000 head of cattle to China per year. The deal had been discussed before the Covid-19 pandemic, in parallel with China and Myanmar's sluggish process to legalize the cattle trade.

Chinese customs provided a list of recommendations for Laos, which included implementing effective animal health inspections and a quarantine system for cattle exported to China.

A major requirement, which Laos has complied with, was to establish a foot-and-mouth disease-free zone in its northern border town, Muang Sing, in Luang Namtha province. This is the official border point where animals depart from the country bound for China.

Exported animals must be quarantined on farms for 45 days and in a quarantine center near the border and within the disease-free zone for an additional 30 days. During this period, traders must feed the cattle and maintain the animals' weight at their own expense.

A similar requirement was imposed on Myanmar’s Kutkai town, which is designated as a disease-free zone and is only a two-hour drive from the export port in northern Muse town.

Despite this progress, and despite Laos having more than one million cattle in the country, only about 3,000 live cattle were legally exported to China from April 2020 to 2021, and only 600 have been exported since then until August this year.

This is mainly due to strict animal health requirements that prevent farmers from jumping on this bandwagon. The low quality of Lao cattle is another major barrier.

Thongpath Vongmany, the Deputy Minister of Agriculture and Forestry, stated last year in a press conference that to meet the Chinese export quota, new hybrid breeds of cattle weighing at least 350 kilograms would be needed to pass China’s checklist, as native Lao cattle typically weigh less than 200 kilograms.

“The strict and highly-demanding checklists prevent us from accessing China’s market. We can only supply cattle through Chinese middlemen, who smuggle the animals across the border," said Chai, who owns a family-run cattle farm in Luang Namtha.

Many Lao farmers secure larger cattle from Thailand and Myanmar, which enter Laos either on foot through the mountainous border or by boat across the Mekong River through the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone in northern Bokeo province.

The area is known for illicit activities such as gambling and the drug and wildlife trade.

Cattle farm owner Ja said that most of the cattle brought from Thailand to her farm are illegal, mainly smuggled by boat or simply walked across the river during low tide at night.

Some traders said they had rerouted their cattle transportation to Phongsaly, Laos’ northern province adjacent to Luang Namtha. They claimed the disease control regulations in Phongsaly are “loose” as cattle exports are managed by a Chinese company rather than by authorities.

In addition to cattle quality, Laos’ effort to formalize the cattle trade is obstructed by its limited capacity for control, surveillance and reporting of animal disease.

In July 2021, China suspended the import of cattle and related products from Laos to prevent the cross-border spread of zoonotic bovine tuberculosis. A lumpy skin disease outbreak was also reported the same year.

As Laos is dealing with all these challenges, some Thai farmers have begun to capitalize on Laos’ insufficient capacity to meet China’s quota.

“Our farms can raise cattle and formally sell them to Laos so that the country can meet China’s quota of 500,000 head per year," said Amnat Srisombat, the Managing Director of the Agricultural Center (Thailand) Co, Ltd. He stated that his company and network could fulfill this quota within three years.

This year, a group of cattle farmers in Thailand's northern Phayao province succeeded in securing a deal to sell cattle to Lao conglomerate Khamphay Sana Group, which received a quota from its government to export 3,000 cattle to China.

Seeing the trade opportunity, the Thai government recently launched negotiations with China to formalize the cattle trade, claiming its livestock industry is advancing in the Mekong region in the aspects of animal health and cattle breeds.

Healthy animals, better human health and trade

A group of cows wander across the grassland of a legal farm in Thailand. VIDEO: Nattakit Meesakul

“If farmers want to engage in formal trade, they are not competitive. The cost of the animal combined with the cost of quarantine nullifies any benefit,” said Srinivasan Ancha, Principal Climate Change Specialist of the Climate Change, Resilience, and Environment Cluster of the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

“They need better-quality animals to get a better price and to afford the cost of quarantine. Only when these three factors – better quality, larger size and lower costs – are achieved, will formal trade truly take off. If it happens in a desirable way, illegal trade will go down.”

The ADB has been active in the Mekong region since 1992, expanding its program from focusing on economic cooperation to agriculture and livestock.

The bank, in partnership with other financial institutions, planned a budget of $270 million for projects to improve livestock value chains in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar – the region’s three weakest countries in transboundary animal disease control – to help smallholder farmers improve livestock health.

This will lead to establishing disease control zones in certain provinces, spanning about a 100-kilometer radius each, with the first cattle breeding centers set up in Cambodia and Laos and the first veterinary vaccines center in Cambodia.

Some other outcomes include an initiative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through better breeding, feed and manure management, and the engagement of the private sector in improving the value chain.

While the project continues until 2031, said Ancha, the ADB hopes to expand efforts if successful, although full control may take decades.

On the other hand, Mekong countries are part of Asia and the Pacific regional steering committee on transboundary animal diseases initiated by the FAO and WOAH. This body focuses on strengthening the coordination of disease responses and monitoring.

However, Ancha said some countries still lack a proactive preventative approach, and sometimes take a “defensive attitude” when a disease breaks out.

“This hesitation is also present within government set-ups, as officials may be reluctant to acknowledge outbreaks due to trade concerns."

To tackle this challenge, the network of veterinarians, scientists, public health officers, livestock officers, farmers and communities have worked together to improve bottom-up disease prevention systems.

In 2014, a mobile app, Participatory One Health Digital Disease Detection (PODD), was launched in Thailand’s northern Chiang Mai province to help community members report unusual disease events in their areas.

Initially, the app was tested and developed in collaboration with 400 local administrative organizations, covering 19,000 farmers, and successfully detected and contained foot-and-mouth disease before it could spread on five occasions – resulting in an estimated loss prevention of five million baht ($144,000).

App usage is expanding to five provinces in Laos – Khammuan, Savannakhet, Champasak, Bolikhamsai and Vientiane – with the developing team planning to extend further to Cambodia and Myanmar when the political situation is more stable.

“Countries can no longer trade by focusing on selling cattle at the lowest prices. If we want to be the kitchen of the world, we need to emphasize food safety practices, including hygiene and disease-free products,” said Manoj Potapohn, an economist from Chiang Mai University who studies the cattle trade.

In Ruili, a Chinese town on the border with Myanmar, the Penghe Cattle Slaughterhouse found itself stranded in the failed attempt to formalize the cattle trade.

The slaughterhouse opened in 2018 when the Chinese and Myanmar governments piloted formal cattle trade with all necessary disease control measures in place. Local residents recall trucks filled with Myanmar’s cattle arriving daily, creating an endless supply of beef for consumers.

However, this profitable business was severely damaged by the Covid-19 pandemic and Myanmar’s civil war.

When operations could not continue, the slaughterhouse’s parent company, Shanghai Pengxin Group, was forced to delist it from the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, marking the group’s first delisted stock.

The company did not announce the reason behind this decision. But some staff have remained in the village near the slaughterhouse, waiting for it to return to operation. Win is one of those.

One sunny day, he looked across the border to the mountain range in Namkham, a town in Myanmar’s Shan State.

The town had been seized by an ethnic armed force after intense fighting with the military, prompting Chinese authorities to shut down the border trade in Ruili, as part of its strategy to pressure the armed groups to implement a ceasefire.

Any formal cattle trade is impossible in this setting. Smuggling is the only option.

“Small businesses like ours are like small ships. We can overturn if the storm is too strong,” said Win, recalling the past vibrant border trade.

Credit and partners

Supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, this collaborative report brings together seven journalists and photojournalists from six media outlets in Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, and Viet Nam to investigate the health and economic impacts of illegal cattle trade in the Mekong region.

Journalists: Kannikar Petchkaew, Gebu, Konlaphat Siri, Aung Myo Htut and Vũ Thanh

Photojournalists: Nattakit Meesakul and Chris Trinh

Editors and contributors: Paritta Wangkiat, Trang Bui, Alan Parkhouse, Tan Hui Yee and Jayalakshmi Shreedhar

Data visualization: Michael Salzwedel

Web development: Rosmy Sophia

The Straits Times

By Kannikar Petchkaew and Gebu

Prachatai

By Kannikar Petchkaew

Prachatai

By Kannikar Petchkaew

Prachatai

By Kannikar Petchkaew

Prachatai

By Kannikar Petchkaew