The report was produced with support from the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN) and Internews’ Earth Journalism Network as part of the “Ground Truths” collaborative reporting project on soils.

ATTAPEU, LAOS — The new high-speed railway has enabled faster fruit exports from Laos to China, attracting more investment in large-scale plantations. However, this growth has come at the cost of deforestation.

Bananas and the “king of tropical fruit” – durians – are very popular in China, but they typically ripen within a few days of harvesting.

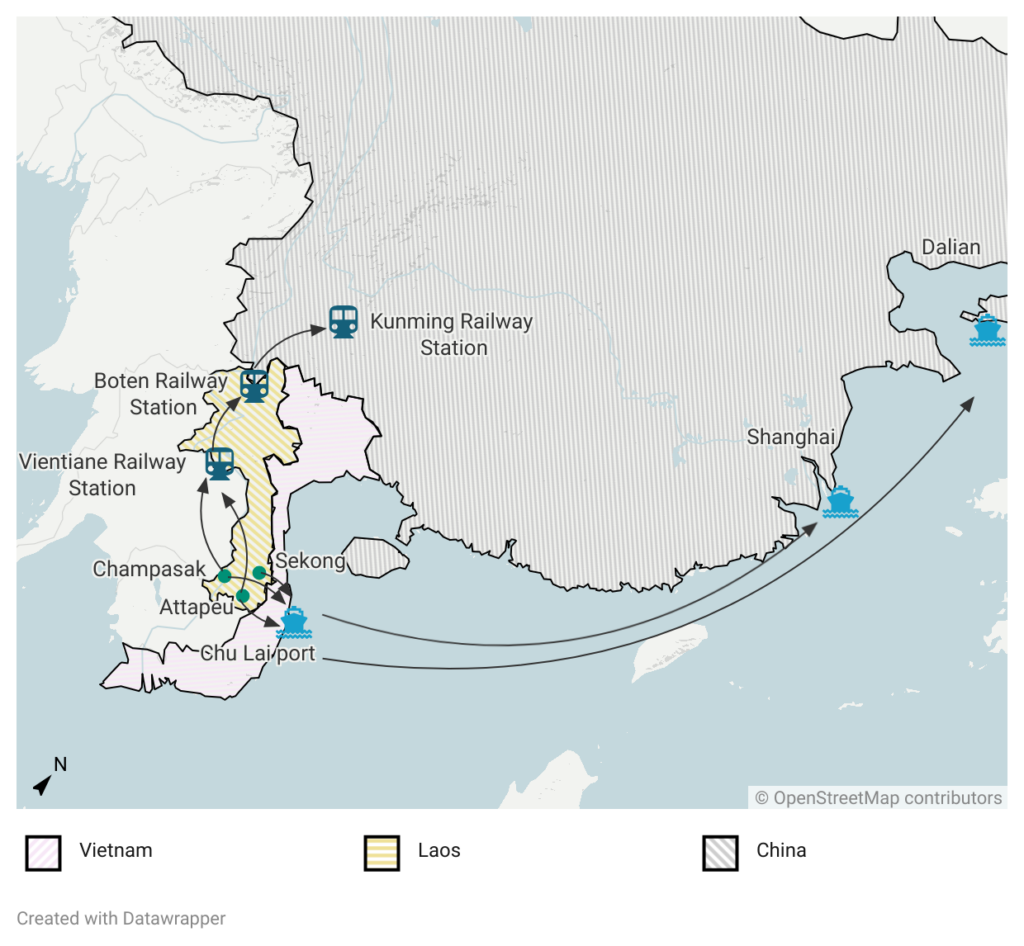

However, that problem was resolved with the launch of the Laos-China Railway in 2021, which has enabled landlocked Laos to deliver its fruit quickly to China’s 1.4 billion consumers.

Operating at speeds of up to 120 kilometers per hour, the high-speed train allows fast-ripening fruit like bananas to travel from Laos’ capital, Vientiane, to China’s southern Yunnan province in just about one day, retaining their “bright appearance and excellent taste.”

Road transportation required at least four to five days to get goods to the border.

However, this progress has come at a cost – deforestation and soil contamination driven by the rush to expand fruit plantations, much of it led by Chinese entrepreneurs.

In Sanamxay district in Laos’ southern Attapeu province, a 14-hour drive from Vientiane, heavy trucks bearing Chinese and Lao license plates lumber along muddy, pothole-ridden roads toward a sprawling banana plantation.

The air is thick with the smell of pesticides and fertilizers. Row upon row of banana trees stretch endlessly, nourished by the fertile soil enriched by sediment deposits from the Xekong River floodplain.

At the plantation office, where Lao and Chinese national flags are visible from afar, a sign identifies the farm as being operated by Chinese company Jin Yao (金耀) – one of many reaping the benefits of Laos’ improved connectivity and access to China’s large consumer market.

“Here used to be a forest,” recalled Chai*, a man in his 40s, gesturing to the rows of banana trees weighed down by heavy fruit. “Here it was too. And there.”

In 2023 alone, Laos lost more than 136,500 hectares of primary forest – an area 3.5 times the size of Singapore – placing it among the countries with the highest rates of deforestation worldwide, according to Global Forest Watch.

Attapeu province has emerged as one of the country’s deforestation hotspots, with forest loss steadily increasing between 2021 and 2023.

Satellite images from Planet Labs revealed that the land now occupied by the Jin Yao plantation was a dense forest until mid-2019. Over time, the green patches thinned and the forest cover gradually disappeared.

This transformation started with the construction of access roads, followed by newly cleared land in late 2021.

Soon after came an office building, a warehouse and rows of banana trees. By 2024, the Jin Yao plantation had grown to 1,000 hectares, making it one of the largest banana plantations in Attapeu.

On Douyin, a popular social media platform in China, an account purportedly linked to Jin Yao shared plans in 2022 to expand the farm to 5,000 mu (about 340 hectares) the following year.

A promotional video showed workers harvesting long bunches of green bananas amid traditional Chinese celebratory firecrackers, marking the first fruit of the plantation’s harvest.

Our reporter contacted Jin Yao via email obtained from Tianyancha, a data technology company providing information about Chinese enterprises,, but the message failed to deliver.

Land-to-capital strategy

For Chinese consumers, bananas are seen as a healthy fruit offering beneficial nutrients, while the sweet taste and pungent aroma of the thorny durian make it a high-class gift, often presented during special occasions such as weddings.

The popularity of both fruit has long encouraged Chinese farmers and agricultural corporations to cultivate them domestically. However, large-scale production has faced challenges due to the limited span of the tropics in China.

As a result, imports have become the primary option for consumers eager to try these exotic fruits.

China ranked as the world’s third-largest importer of bananas last year, following the United States and the European Union, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization.

Despite a sluggish economy, China imported 95% of global durian exports in the same period, totaling nearly US$7 billion – a 66% increase from the previous year – making durian the country’s leading imported fruit.

Thailand and Viet Nam are the main suppliers of durian, while Laos is shaping up as a vast orchard catering to the growing demand from Chinese consumers.

Land is one of Laos’ most valuable assets, and the government has leveraged this by offering investors long-term leases and concessions, some lasting up to 50 years, under the so-called “land-to-capital” strategy.

A report published in 2020, based on land transaction data from 2014 to 2017, revealed that deforestation occurred in nearly a quarter of the land deals between Laos and foreign investors.

In addition, the government has authorized investors to use more than 110,000 hectares of land within national conservation and protected forest areas, converting them into “production forests” – meaning areas where trees are planted for the purposes of agriculture and logging.

While agriculture accounts for only 10% of this land, experts believe this figure has significantly increased due to the surge in Chinese investment in Lao agriculture in recent years.

In 2018, in response to local communities’ complaints of land grabbing and alarming deforestation rates, the government issued a moratorium on land deals to suspend new concessions for mining, rubber and eucalyptus plantations.

However, new land deals have continued to be approved since then, particularly after Laos faced an economic crisis after the Covid-19 pandemic, which led to high inflation.

In a bid to generate quick revenue to repay its debts, with China being the primary creditor, the government has increasingly sought investment in land.

“The government once tried to regulate and control projects, but facing the pressure of an economic crisis, they had to quickly attract investment and overlooked environmental standards,” said a Lao expert, who requested anonymity for safety reasons.

Agro-development under China’s BRI

Located 30 kilometers from Jin Yao’s banana plantation, the once-verdant expanse of forest has been replaced by endless rows of banana plants and durian saplings. Since 2020, at least three plantations, covering a total of 650 hectares, have been established in this area.

Residents reported that part of the old-growth forest was cleared for roads and plantations by private companies.

During a site visit, our reporter found remnants of ancient trees scattered near the farms.

One of these farms belongs to the owner of Guangxi Jianda Jinniu Agricultural Technology Co, Ltd (建大), based in China’s Sichuan province, known for its award-winning banana brand called “Jianda Golden Cow.”

Residents stated that parts of the land were once cassava fields operated by locals, who are now accused of encroaching on the forest.

“The authorities and the [Chinese] companies use the fact that cassava fields were once forested to seize land from the locals. If you disagree, they will still take it, uproot your cassava, and bring in bananas and durian,” said Jay*, a member of the Indigenous Laven community in Attapeu.

She claimed that 12 hectares of land her family cleared four years ago were recently reclaimed by the government and handed over to a newly arrived foreign fruit company.

Our reporter was unable to reach Jianda as there is limited public information about the company’s contacts.

“There’s a significant lack of law enforcement in this country. Environmental protection regulations exist only on paper,” said Denis Smirnov, an independent environmental investigator who monitors infrastructure projects in Laos.

After reviewing satellite images of forests based on coordinates provided by our reporter, he could not help but remark: “All this is sad news.” Forests in areas he visited years ago for his research are now being destroyed at a breakneck pace.

The Laos-China Railway plays a significant role in the supply chain, as our reporter observed cardboard boxes full of bananas bearing the Jianda logo being loaded onto trucks and transported to Vientiane, the railway’s starting point.

The railway is a key component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, known as BRI, which aims to promote a “community with a shared future for mankind” in Southeast Asia.

The initiative highlights agro-industry as one of its key areas and includes a project titled “Forest Restoration and Full-Scale Eco-Agricultural Development,” with durian identified as the principal crop along with the emphasis on forest restoration and green agriculture.

Driven by this project, the Sichuan-based agricultural technology company Jiarun (嘉润) arrived in Laos after the Covid-19 pandemic with a $152 million investment and has quickly become one of the largest agricultural investors in the country.

The company’s bright yellow headquarters, located in Sanamxay district, stands out with a large signboard at the front, surrounded by forest and cassava fields. Nearby, durian trees planted nearly two years ago have now spread rapidly, thriving like weeds.

Here Laos has leased 5,000 hectares of land to Jiarun for 50 years, with the hope of boosting the district’s economy. The company plans to dedicate 3,000 hectares to creating the world’s largest durian plantation, with 200 varieties of the fruit.

Jiarun will cooperate with the Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, under the administration of China’s Ministry of Agriculture, to develop the farm and advance forest restoration efforts.

Additionally, the company has pledged to share agricultural technology, create more than 5,000 local jobs and fund 20 schools and 20 clinics or health centers for local communities over the next five years.

Jiarun’s verified account on Douyin shared a video clip of a backhoe falling a large tree in the middle of cleared land, likely for planting durian.

Though the post’s caption does not mention the location, the account’s bio says the company was granted a land lease in southern Laos. Our reporter contacted Jiarun via its website and received no response at the time of publication.

According to an environmental impact assessment for Attapeu province, the farm is within the Xe Khampho-Bang Wilai national production forest area, which remains rich in natural resources and wildlife.

Viet Nam’s wealthiest cash in on fruit harvest

Before Chinese companies entered southern Laos in large numbers, Vietnamese banana plantations had already been established in the country for more than a decade.

Viet Nam has leveraged land capital in Laos to produce bananas for export to China, with Vietnamese-exported bananas accounting for nearly half of China’s banana imports.

Expanding durian cultivation in Laos is part of Vietnamese agro-companies’ strategy to compete with Thailand and Malaysia, the region’s major durian exporters.

With its closer proximity to China, Viet Nam can lower fruit prices by shortening transportation distances, helping make China’s vision of “durian freedom” – enjoying the fruit without concerns about high prices – a reality.

Hoang Anh Gia Lai Joint Stock Company (HAGL) is one of the leading players in Laos’ durian industry, and has obtained 1,500-hectare plantation in southern Champasak province, according to a local report.

In 2007, the company secured a 35-year lease on 10,000 hectares of land in the Phouvong and Saysettha districts of Attapeu province for timber harvesting and rubber cultivation.

Later, HAGL’s chairman, Doan Nguyen Duc – formerly one of Viet Nam’s top 50 wealthiest men – announced a shift toward banana and durian cultivation to capitalize on changing market opportunities.

He revealed during the company’s shareholder meeting last year that the Chinese market accounted for between 60% and 65% of the company’s production in both Laos and Viet Nam.

Satellite imagery from late 2020 to early 2021 shows that banana trees have replaced cleared forest areas adjacent to the company’s plantation in Saysettha district.

A study by Miles Kenney-Lazar, a scholar at the University of Melbourne who studies plantations in Southeast Asia, revealed that the Lao government had bypassed land surveys, as well as environmental and social impact assessments, in the concession areas, increasing the risk of further deforestation.

“When I saw the forests of my homeland being cut down, my heart ached,” said Vong*, a member of the Laos Communist Party in Attapeu, referring to HAGL’s arrival in his hometown.

“But I don’t blame the company because they built roads and hospitals for our province. I just blame the government for giving them so much forest.”

The NGO Global Witness published a report in 2013 that accused HAGL of evicting communities in Laos’ and Cambodia’s forested land to make way for rubber plantations. Duc denied this in a Reuters’ report, saying the accusations were “fabrication and vilification.”

Our reporter contacted the company via email, but did not receive a response by the time this report went to press.

In 2021, HAGL’s banana farm in Phouvong district was transferred to Tran Ba Duong, the chairman of Thaco Group and one of Viet Nam’s five wealthiest businessmen listed by Forbes this year.

From the satellite image, the rim of the farm is less than 50 to 100 meters from the Nam Kong River, which provides water to local farmers. Such a narrow strip of buffer may result in contaminated water if agrochemicals are applied without protection measures.

This was followed by the Lao government recently permitting Thaco to establish a 27,000-hectare agricultural complex, which will plant bananas and durians across Attapeu and its neighboring Sekong province.

Bananas from HAGL and Thaco are first exported to Viet Nam before being shipped to major Chinese ports such as Dalian and Shanghai.

Forest loss accelerated by corruption

Siri*, an expert on Laos’ development who prefers a pseudonym for fear of state percussions, said land leases for banana and durian plantations have brought better economic value when compared to casinos – most of which are in the country’s north.

According to a report by the Vientiane Times, Laos earned $1.4 billion from agricultural exports to China in 2023, a 20% increase from the previous year, with bananas among the top export commodities.

Durian was also expected to generate more revenue soon, as China and Laos agree on the fruit exports quota.

Stuart Ling, an expert working in Laos for more than two decades, raised concerns about the government’s ability to monitor the projects in concession areas.

While land concessions are often granted near natural forest areas, he said there is no guarantee that investors won’t encroach on them. Some locals also take advantage of new roads, built by foreign companies, to claim forest areas for cash crop plantations.

Plantations have been launched without the requirement for Environmental and Social Impact Assessments or resettlement plans, he said, reflecting the close ties between the Lao government and investors.

A leaked 2015 report revealed that large-scale illegal logging commonly occurred outside designated concession areas and was often facilitated by corruption.

In August, Attapeu authorities uncovered eight companies and two individuals who had illegally seized more than 5,800 hectares of protected forest in Sanamxay, though their names have not been disclosed.

The root of the problem may lie in investors not receiving clear boundary data from the government, according to some experts, as forest zones are often poorly defined and inadequately monitored.

In many cases, encroachment is deliberate – driven by investors’ desire for land or extra profits from illegal logging in forest areas.

“They often don’t care about the boundaries between natural forests and production forests. And because there are no consequences for violating land use maps, they have even less respect for them,” said Siri.

“The laws in Laos are applied irregularly and subject to political interference so that companies who are willing to pay have normal approval processes overlooked.”

The US International Trade Administration has highlighted corruption as a major obstacle in the Lao market, where bribery and payments are ingrained in the business culture.

Companies from countries lacking legal or ethical frameworks to combat corruption have exploited the situation, obtaining approvals and concessions from the Lao government.

Our reporter sent an email to the address provided on the website of Laos’ Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, but it failed to deliver. A message was also sent via a contact channel on the National Assembly Office’s website, without any response.

Ian Baird, a political ecologist at the Department of Geography, University of Wisconsin–Madison, said inflation and economic pressure have deepened corruption in Laos.

Local officials, earning meager salaries, are often compelled to take on side jobs with investors to make ends meet.

“They can arrange for investors to acquire the land, and the investors pay them. This is very common in Laos,” he said.

Political ties drive farm expansion

The partnership between the Lao government and Vietnamese and Chinese investors signifies more than just a market-driven collaboration.

Beneath the surface lies the influence of geopolitical dynamics, with major investors receiving support from their home governments, as well as Laos, to consolidate influence.

For Beijing, Laos is a crucial link in its bid to extend its sway across Southeast Asia. Investments in the country are seen as integral to President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative.

For Hanoi, Laos remains the top destination for its outbound investments. According to Nguyen Khac Giang, a visiting fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Viet Nam’s vigorous investment in Laos serves multiple strategic objectives.

“While officially framed as strengthening traditional friendship and mutual prosperity, it’s also clearly about securing Viet Nam’s strategic interests. Hanoi wants to maintain its strategic influence in Laos at a time when China’s economic and political presence in the region continues to grow,” said Giang.

In addition to investment flows, Vientiane has received a steady stream of aid packages and concessional loans from both governments.

With close ties to businessmen, Laos’ high-ranking officials have occasionally shown gratitude to investors from neighboring countries.

Somsavat Lengsavad, Laos’ former Standing Deputy Prime Minister, once stated: “The government and people of Attapeu will always remember the generous, unconditional assistance of the Hoang Anh Gia Lai Group,” acknowledging the company’s significant investment in local infrastructure, job creation and revenue generation.

Lao central government officials have also visited the plantations of HAGL and Thaco in Laos and their headquarters in Viet Nam.

Similarly, the Vice-President of the Lao National Assembly has praised Chinese company Jiarun as an exemplary model of agricultural collaboration between the two nations.

The company’s chairman has personally visited top Lao officials, openly expressing his gratitude to the Deputy Prime Minister for his “trust and support.”

Such strong support leads experts to argue that it is unlikely penalties will be imposed on those violating environmental regulations.

“They [local authorities] simply can’t act beyond their power,” said Ling. “The companies undertaking deforestation have usually been approved by the higher levels of government, which makes it difficult for them [local authorities] to act.”

Back in Attapeu, Chai has watched helplessly as trees were felled after the arrival of a Chinese large-scale fruit farm.

“The authorities said they would build roads, but I haven’t seen anything since they arrived,” he said.

*Pseudonyms are used for the safety of interviewees.

**The scrolling map used in this story was created by the Rainforest Investigations Network using satellite imagery provided by Planet Labs.

This story is the first of two investigative reports exploring the impact of large-scale agriculture on deforestation and soil quality in Laos, using satellite imagery from Planet Labs to identify deforested areas.

The report was produced with support from the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN) and Internews’ Earth Journalism Network as part of the “Ground Truths” collaborative reporting project on soils.