ĐỒNG THÁP, VIỆT NAM – Almost one year after the Hồ Chí Minh City-Cần Thơ highway was launched, 70-year-old farmer Võ Văn Cựu still finds it hard to reach his rice field.

“We don’t have a local road to access our fields,” the farmer from Châu Thành district lamented.

“For the past two years, every farming season, I’ve had to borrow water from the neighbors. Without a local road, we had to build trails that go past people’s houses to reach the other side. It’s a hassle,” Cựu explained.

Highway construction has disrupted irrigation canals and affected tens of hectares of farmland, farmers in An Khánh commune in Châu Thành district say.

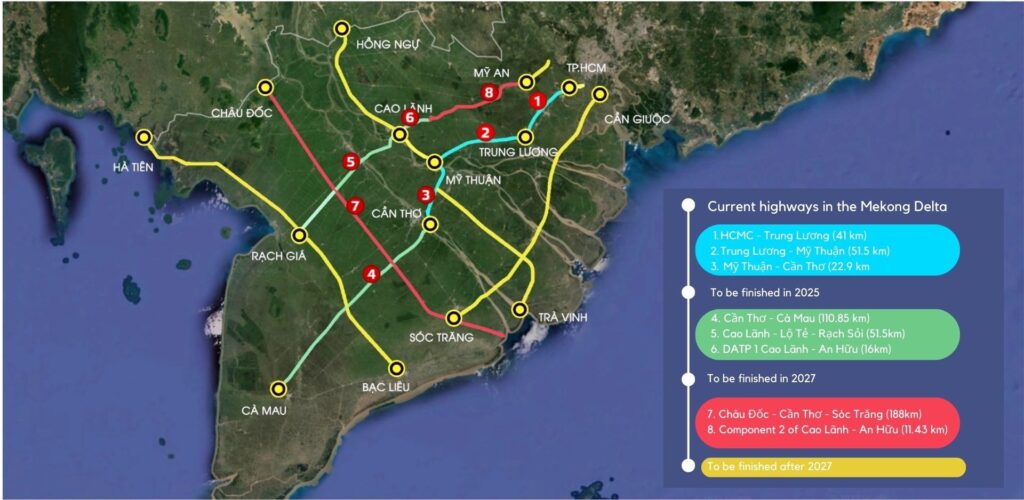

In the Mekong Delta, more than 406 kilometers of highways are under construction, with 207km set to be finished by 2025. Viet Nam is aiming to expand its high-speed road system by 1.5 times before 2025, and 2.5 times before 2030 – reaching a total length of 5,000km.

About one fifth of this target will be built in the delta.

The plan aims to ease long-standing bottlenecks in the delta’s transportation infrastructure. Rapid development, however, runs the risk of disrupting lives and livelihoods in a region already highly vulnerable to climate change.

According to Trần Văn Lý, An Khánh commune’s land and agriculture official, by the end of 2024 – one year after the highway opened – up to 22 households are still waiting for compensation for damage to their homes.

To construct 188km of the Châu Đốc-Cần Thơ-Sóc Trăng highway and 111km of the Cần Thơ-Cà Mau section of the north-south highway, nearly 1,915 hectares of land belonging to about 9,600 households was confiscated, according to data from the Ministry of Transport.

“We can’t pump water from the canals in the dry season and drain it in the rainy season,” said Lê Văn Hai, a resident of Vị Thủy district in Hậu Giang province, who has been struggling to irrigate his 26 hectares of rice.

At the end of 2024, to prevent citizen complaints and disputes, Hậu Giang province directed departments and local authorities to temporarily channel water into farmlands affected by the development.

A representative from the two expressways’ project investor, Mỹ Thuận, told this reporter they were still waiting for additional funding for supplementary access roads and irrigation canals. Hậu Giang province alone, they estimated, needed about 22km of temporary canals.

Potholes and sinkage

Unlike other regions, highways constructed in the delta are at much higher risk of sinkage.

Many sections of existing highways such as the Lộ Tẻ-Rạch Sỏi (Cần Thơ-Kiên Giang highway), Quản Lộ-Phụng Hiệp (Hậu Giang-Cà Mau highway) and the National Highway 61C (Cần Thơ-Vị Thanh highway), have all sunk significantly after a period of use.

Even the newly opened Mỹ Thuận-Cần Thơ road has already shown signs of sinkage around bridges and abutments, with some parts slightly undulating.

Phạm Đức Trình, the project director of the Mỹ Thuận-Cần Thơ and Cần Thơ-Hậu Giang expressways, said the agency was aware of the subsidence and regularly instructed contractors to make repairs, as the project is still under a two-year warranty.

“Subsidence in the Mekong Delta is nearly unavoidable, as the entire project runs through weak soil,” Trình explained. “Over its lifespan, the roads could sink by up to 30cm, the most significant sinkage occurring in the first two years.”

According to the Ministry of Transport, highway construction costs in the Mekong Delta are significantly higher than in other regions due to weak soil. While the average cost to build one kilometer of a four-lane expressway in Vietnam is about 186 billion VND (US$7.2 million), in the Mekong Delta, this figure can be 1.3 to 1.5 times higher.

Take the two key highways now under construction, the Cần Thơ-Cà Mau and Châu Đốc-Cần Thơ-Sóc Trăng road, for example. Each kilometer of these highways costs more than 248 billion VND ($9.7 million) and 238 billion VND ($9.3 million), respectively – up to 1.33 and 1.28 times the national average.

The high cost is a key reason why expressway development in the Mekong Delta has lagged behind other regions for years. Attracting private investment remains challenging, and many projects had to be built in phases, even if it meant a lack of key features like emergency lanes.

For example, without weak soil adaptation, the 51.5km Lộ Tẻ-Rạch Sỏi highway cost 6,355 billion VND (nearly $250 million) to build. After only two years of use, potholes started to appear.

When its warranty expired in June 2024, the Ministry of Transport had to allocate another 750 billion VND ($29.3 million) for upgrades for this road to qualify as a highway.

Sand shortage

A severe shortage of construction materials like sand and gravel posed another challenge to the government’s ambition of connecting the country’s rice bowl.

Of the 1,542km of expressways under construction nationwide, more than 406km are in the Mekong Delta, with 207km expected to be completed by 2025.

The Ministry of Transport estimated that nearly 54.5 million cubic meters of sand was needed to complete the highways under construction in the Mekong Delta. This demand is significantly challenging, as the delta’s sediment supply is already critically low, and more mining would only exacerbate erosion.

The shortage explains the daily, monthly and yearly supply quota applied on current highway projects, despite the total amount allocated on paper. Even with the quota, supply regularly falls short, delaying progress, particularly in the crucial loading phase – which is essential for soil settlement before any further construction can begin, and typically takes 10 to 12 months.

For example, the Cần Thơ-Cà Mau highway requires 15 million cubic meters of sand to complete the loading phase by 2024, but by December 2024, it was still short 3.39 million cubic meters.

Phạm Đức Trình, the project director for the Mỹ Thuận-Cần Thơ and Cần Thơ-Hậu Giang highways, likened the Delta soil to a sponge.

“When wick drains are inserted and sand is layered on top, groundwater slowly seeps out, causing the soil to settle and harden over time. This step takes a long time before other construction phases can begin,” he explained.

Due to the sand shortage, contractors have resorted to importing sand from Cambodia at high costs to minimize delays.

They are also racing to make up for lost time – an approach fraught with risks. In October 2024, former Minister of Construction Nguyễn Thanh Nghị (now Deputy Secretary of the HCMC Party Committee) warned at a conference that hasty construction could compromise critical processes like ground loading, weak soil treatment and asphalt paving.

The Mekong Delta is a low-lying region, with key areas submerged from 3 to 4.5 meters during floods. A strict oversight of flood risks and subsidence is needed for construction projects, Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development Lê Minh Hoan said at the same conference.

Elevated expressway – a challenged alternative

Amid severe sand shortages and subsidence risks in the delta, the elevated highway has garnered some support as an alternative.

According to experts, the advantages include minimization of land clearance, less dependence on sand, a high adaptability to low terrain, weak soil and rising sea levels.

Elevated highways also minimize disruption to water flows, flood drainage, the natural ecosystems and local livelihoods.

Trần Bá Việt, a former Deputy Director of the Institute of Construction Science and Technology and Vice-President of the Vietnam Concrete Association, argued that while elevated highways have higher initial costs, their long-term lifecycle expenses are lower than ground roads.

According to his calculations, a 1km ground-level highway costs 232 billion VND ($9 million) initially, but rises to 315 billion VND ($12.3 million) over 50 years due to maintenance and other expenses.

In contrast, a 1km elevated highway using ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) costs 264 billion VND ($10.3 million) upfront, but only 303 billion VND ($11.9 million) over the same period.

Nguyễn Thế Minh, the Deputy Director of the Investment Management Department (Ministry of Transport), acknowledged the technical advantages of elevated highways, especially for challenging terrains and weak soil conditions.

Real-world applications, such as the 13km elevated section on the HCMC-Trung Lương expressway and similar stretches on the Thái Nguyên-Chợ Mới, Diễn Châu-Bãi Vọt and Quy Nhơn-Chí Thạnh routes, have demonstrated their effectiveness.

However, with limited resources, the biggest obstacle remains the high upfront investment costs.

According to the Ministry of Transport, the cost of building elevated highways is 2.62 times higher than embankment roads. With this disparity, adopting elevated highways for expressways in the Mekong Delta could drive the total project investment up by 1.69 times.

If the Cần Thơ–Cà Mau Expressway (two segments), Châu Đốc-Cần Thơ-Sóc Trăng Expressway (four segments) and Cao Lãnh-An Expressway (two segments) were built as elevated highways, the total investment would surge from 79.7 trillion VND ($3.1 billion) to 134.7 trillion VND ($5.3 billion) – a difference of nearly 55 trillion VND ($2.2 billion).

“We in the industry actually prefer elevated highways – they reduce risks, prevent sinking and are easier to manage,” said project director Phạm Đức Trình.

Trình nevertheless acknowledged that the possibility for planned projects to be switched to elevated highways is low, due to limited funding and the complexity of changing project plans.

The current solution instead is to extend bridge sections in areas with particularly weak soil.

While the benefits of these ambitious construction projects are significant, local residents like Cựu and Hai in Hậu Giang are still reeling from the impacts. What they hope for is the timely construction of access roads and irrigation canals – lifelines to keep their livelihoods intact.

This article was written in Vietnamese, translated to English using AI and edited by Mekong Eye. It was originally published on Thanh Nien News on December 30, 2024.