KOH KONG, CAMBODIA – Despite undergoing a review process, the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project continues to threaten Indigenous livelihoods with land restrictions and arrests, leaving land disputes unresolved and highlighting broader flaws in global carbon credit markets.

Sitting beside her recently jailed husband and their seven-year-old son in their stilt house near Koh Kong’s protected forests, Chey Nov fought back tears.

Since her husband’s arrest last summer for allegedly encroaching on land his family had rotationally farmed for decades, their money had dried up and their children’s health had worsened.

On June 27 last year, 39-year-old Nov said she was cultivating a family plot recognized by Thmar Dounpov commune authorities with her husband, Pork Nget, and their children.

Deep in Koh Kong’s Thmar Baing district, their farmland lies less than three kilometers away and is surrounded by the demarcated boundaries of a carbon credit project that covers more than one-third of the province.

While they weeded, forest rangers arrived. Nov, who, along with her family is part of the indigenous Chorng community, said they were from the Environment Ministry and Wildlife Alliance (WA), a US-headquartered nonprofit that runs the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project (SCRP).

The rangers claimed that the plot lay on protected forest land under the SCRP, whose issuance of new carbon credits had been halted at the time amid allegations of human rights abuses.

Rangers from the ministry arrested Nget and handed him over to the provincial court, where he was charged with encroachment. He was accused of cutting down protected trees to clear land for rice farming and of lacking proper ownership titles for his family’s land.

He received a five-year prison sentence, later suspended, although the charges remained.

“I do not dare enter the farm now because the organization [Wildlife Alliance] does not allow it. If I go back, I fear they [forest rangers] will arrest me again,” said Nget.

His arrest came during the project’s nominal review phase from June 2023 to September 2024, before it was reinstated shortly after.

During the review process, SCRP partners were supposedly addressing past grievances and ensuring that their methods for protecting the Southern Cardamoms balanced environmental conservation with the rights and livelihoods of the area’s generational communities.

However, investigations and remediation efforts appeared to have largely come from the very groups accused of wrongdoing or those with deep conflicts of interest.

Indigenous communities near or within the project zone say little has changed, with efforts leading only to tokenistic investments in the community. Ancestral lands remain restricted, arrests and intimidation persist, and transparency is still lacking.

More than five months after its reinstatement following a damning 118-page report from Human Rights Watch (HRW) detailing abuses, the SCRP’s promised restitution looks to many to be more like damage control.

Conflicted interests and skirting compliance

The 465,000-hectare (1.15-million-acre) SCRP in the dense rainforest in southwest Cambodia receives its carbon credit certification from Verra, a certifier of voluntary carbon offsets for 97 REDD+ projects across the world.

After Verra suspended the project in June 2023 for an “impartial” review of the grievances raised, it turned to several Validation/Verification Bodies (VVBs) – including SCS Global Services, Aster Global and Aenor – which had previously provided verification services for SCRP.

They were tasked with reviewing the project’s earlier work in light of the allegations.

Notably, every party Verra engaged to review HRW’s allegations stood to face financial or reputational fallout if the allegations were confirmed.

No Verra staff traveled to Cambodia for a fact-finding mission, instead relying on self-audits and progress reports filed by WA or the VVBs, according to a report from conservation news outlet Mongabay, as well as a carbon pricing watchdog.

A Verra spokesperson also confirmed that the organization’s project reviews are entirely desk-based.

“As a certification body, Verra does not conduct on-site investigations or directly validate projects,” they said.

After being presented with details of Nget’s arrest and his testimony, the organization said it was unaware of the incident which took place during the review period.

But despite these many conflicts of interest, Verra relied on its grievance mechanisms and reinstated the SCRP, which experts in the carbon credit market say does not meet professional standards.

Verra is approved by the Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), an independent governance body that helps maintain a global standard for high integrity in the voluntary carbon market.

“Verra’s review of HRW’s allegations of indigenous Chorng rights abuses tied to SCRP wasn’t impartial – violating ICVCM’s Core Carbon Principles,” said Lindsay Otis, a global carbon markets expert at Carbon Market Watch. Otis, who filed a complaint to ICVCM, said Verra failed to meet the framework’s grievance mechanism rules.

“Verra did not employ an impartial third party – such as an external auditor not involved in any of the prior validation or verifications,” she said. “This situation creates an inherent conflict of interestsince it’s in their reputational and financial interest to ‘overlook’ any problems.”

Otis questioned whether Verra would face consequences for skirting ICVCM rules or if it would keep its approval and carry on as usual.

“If Verra is not held accountable for its actions in this regard, it can set a troubling precedent that VCM actors do not need to follow these rules because accountability and enforcement is lacking,” she said.

This could lead to weakened safeguards for indigenous peoples and local communities, erode trust in the system and drag down credit quality, Otis warned.

WA, close with Environment Ministry, defends role

When asked for comment on its policy revisions for implementing the SCRP since being reinstated and the alleged injustices that occurred during the review period, WA – long criticized for taking aggressive conservation methods – pushed back on three points.

It stressed that WA had no law enforcement authority, claimed communities “overwhelmingly” support SCRP, and insisted the project had significantly improved local livelihoods. WA put it in bold during email correspondence.

The conservation group also insists it has addressed all accusations in full – both in a nearly 10,000-word open letter to stakeholders in Dec. 2023 and in a public statement after Verra lifted its hold on the project.

The Environment Ministry and its bureau in Koh Kongdid not immediately confirm, but WA’s claim that it had no law enforcement authority is blurred by its frequent presence at arrests.

Like the patrol team present during Nget’s arrest, his brother Pork Chuon was also caught up in an enforcement action that allegedly included WA staff members.

Chuon said he broke his leg while fleeing military police and WA members near the disputed farmland in Thmar Dounpov commune in June 2024, only weeks before Nget’s arrest.

Chuon claimed a “foreigner” WA staff member and military police chased him while he was fishing. As he tried to escape by jumping across a stream, he fell, hitting his knee on a rock and fracturing his patella. He added that military police fired a shot into the air to intimidate him.

On the way back from meeting the Chorng community, reporters stopped at an Environment Ministry bureau, about 53km from Thmar Dounpov commune, to seek an interview with WA staff reportedly operating out of the government building.

Rangers and military police questioned the reporter team before allowing a brief exchange with a foreign WA staff member, who declined to comment and referred them to WA’s Phnom Penh office.

Chhi, Chuon’s wife, claimed forest rangers and WA staff destroyed their rice storehouse after chasing her husband. She showed reporters the ruins.

But WA denied the claim, saying they were unaware of any property destruction or confiscation in Chhay Areng district, where the family lives.

WA said it was only aware of Nget’s arrest during the project’s review period and had not received any request from the family to help with psychological or financial challenges. However, it said Nget’s family sought its support in court proceedings.

“As we do in all such cases, project staff contacted the family to offer access to pro bono legal representation,” WA said.

At the heart of these contested enforcement actions is Cambodia’s precarious land tenure system, mired in bureaucratic red tape – particularly for indigenous communities – and the country’s struggle with one of the highest deforestation rates in the world.

WA, meanwhile, argued that many farmers in the project area, where more than one third of the population relies on agriculture, whose land cultivation has been brought into question, were not practicing sustainable shifting cultivation, but ecologically damaging slash-and-burn farming in protected areas.

“Nget has done nothing wrong,” said Hoeug Pov, president of the Chorng community, when asked about his farming practices.

“He was simply practicing traditional farming, as our people have always done.”

Disputed land, confusing maps

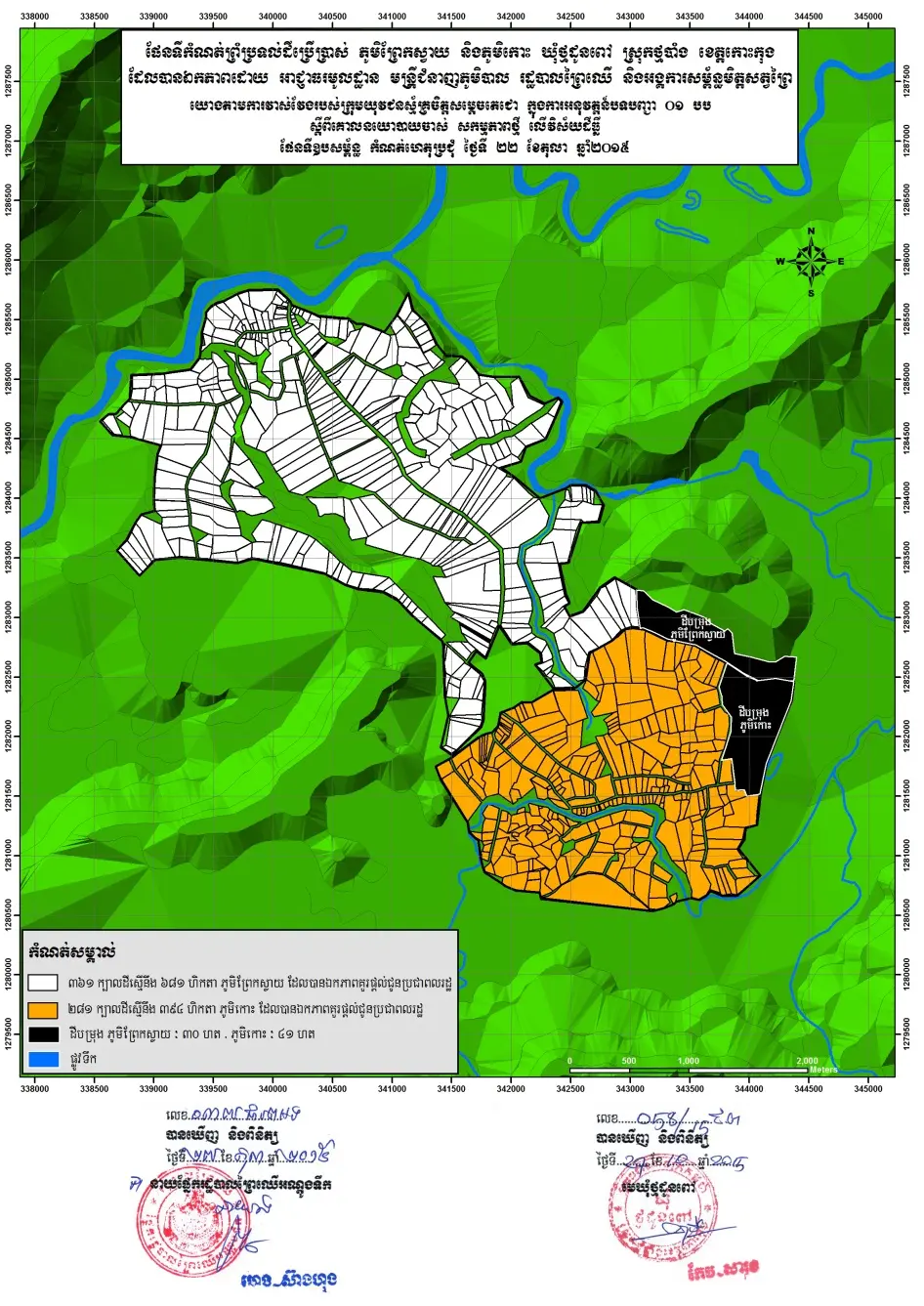

Beyond disputes over their farming methods – which they also say follow a cyclical system with fallow periods – Nov and Nget provided reporters with an “Order 01BB” document, issued under a 2013 national decree that surveyed land and was meant to title it for rural residents, with local commune chiefs determining authorization.

The document recognized the plot where they planned to farm rice in 2024, which had been assigned to Nget’s brother and granted to them for cultivation.

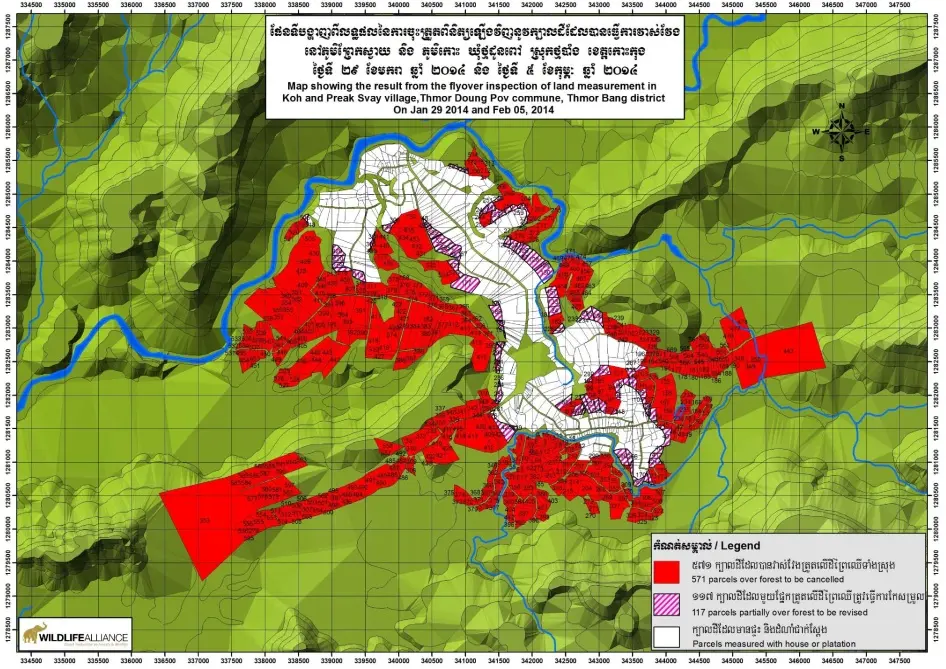

However, a map of Order 01BB surveyed plots in Thmar Dounpov commune, published by HRW, highlights 571 “contested” parcels marked in red, overlapping forested land – including the farmland used by Nov and Nget.

It wasn’t until October 2015 – the same year the SCRP was being surveyed – that government officials, in partnership with WA, finalized a second map that removed most of the previously contested plots, which many indigenous farmers believed they were entitled to.

Nget asserted that on the day of his arrest, there were no clear signs marking the land as within the SCRP’s boundaries. Photographs from the day of his arrest show no signs prohibiting farming or indicating a protected area.

But in October, reporters found a prohibition sign posted near the parceled area, suggesting it was added after his detention. In an email, WA confirmed that the sign was in fact added after Nget’s arrest.

Since the SCRP implementation, WA claims to have installed 1,349 demarcation posts to distinguish forest and community areas, while acknowledging it has difficulty marking the boundaries of a 450,000-hectare protected area.

Many villagers reporters spoke with – including Chorng and Thmar Dounpov commune chiefs and other community leaders – said the maps WA provided to outline the SCRP’s boundaries were either too low-resolution or too complex for illiterate residents.

That, they said, fueled fears about where they could still practice rotational farming.

These concerns were reportedly raised during Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) meetings over the past year. The sessions, meant to update residents on project policies, addressed HRW allegations and gauged community support for the SCRP, and were a key requirement for project validation.

Nov attended the 2024 FPIC meeting only weeks before her husband’s arrest. She even initially voted in favor of the SCRP, saying WA’s maps were too vague for her to tell if the land she planned to farm that year would fall inside the protected zone.

Community approval and alternative livelihoods

As seen in Nov’s case, the reported outcomes of this meeting appear misleading, if not outright skewed.

In a self-reported progress update filed to Verra in August 2024, WA pointed to improvements in its handling of community concerns, highlighting the expansion of “grievance boxes” across the project zone.

It also emphasized that the FPIC session held that year showed more than 80% support from 15 communities in the carbon credit zone.

For the most impacted indigenous communes – Pralay, Chumneap and Thmar Dounpov – WA reported support levels of between 81% and 88%. The figures came from a binary yes-or-no consent survey, a method HRW has criticized since February 2024, but one that cleared audits by Verra and the VVBs.

But WA’s own documents detailing population surveys, conducted in the communes in 2018, reveal a stark gap between the number of residents attending annual consent consultations and the total commune population.

For example, only 240 Pralay villagers attended the June session – less than one third of the commune’s 763 residents. The figures are similar for the Chumneap and Thmar Dounpov communes as well.

In an email, WA defended this, calling the attendees “household representatives” and claiming the process was verified by “third-party auditors” – the VVBs.

However, in its August progress report, WA does not seem to clarify this point or the data.

In March, WA is expected to submit another progress update, according to Verra.But for many residents, paperwork and progress reports do little to ease the uncertainty.

Farmers like Nget, his family and others who have lived in the Cardamoms for generations, say past run-ins with WA and forest rangers – several of whom had their crops burned – along with ongoing land title hurdles, have cast a long shadow over their rotational farming practices, central to their way of life.

For WA, the solution to their trouble is in “alternative livelihood” programs, which it says the project has invested more than $3 million in between 2023 and 2024 – in addition to water wells, healthcare and education facilities across the communities impacted by the controversial REDD+ project.

“Their project helps us very little,” said Nheok Chhoeun, another Chorng community member. “They provided wells, hospitals, schools and solar energy, but there are still many shortcomings, such as a lack of land for agriculture or building community housing. I wanted them to set aside land, especially for rotational farming, for the people,” she said.

These ongoing shortcomings come as other REDD+ projects make headway in Cambodia, including the neighboring Samkos REDD+ project.

Open questions remain about whether validators and implementers can balance forest conservation with the protection of livelihoods for indigenous communities in Cambodia and across other carbon credit schemes in the global south.

This has become an existential question for the carbon market, whose confidence and value have steadily eroded in recent years.

Credit: This story was first published on March 3, 2025, by CamboJA News