How Myanmar’s gold rush threatens international rivers

By Kannikar Petchkaew

Published on April 28, 2025

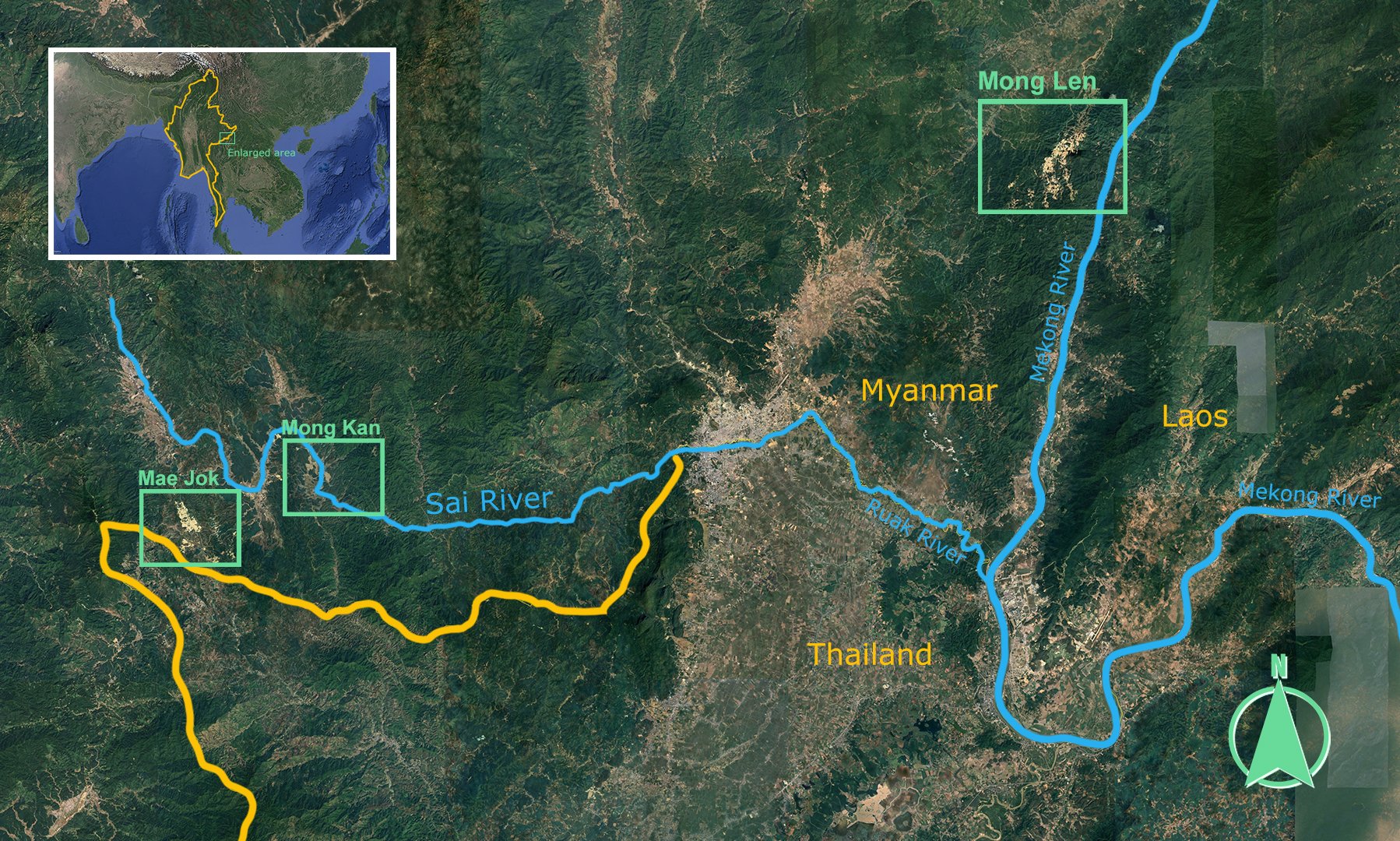

SHAN STATE, MYANMAR – Unregulated gold mining in eastern Shan State raises concerns about the risk of cyanide contamination in key transboundary rivers near the Thai–Myanmar border, including the Mekong.

When Sai U, a 35-year-old farmer from a quiet village in Mong Len, Tachilek township, near the Thai border, watched his cattle approach a local pond for a drink, he never expected what would happen next.

“They drank the water, took a few steps, and just collapsed,” he said, recalling the moment with disbelief.

The pond had been fed by Nam Kham – the “Golden River” – a stream that flows from Loi Kham, or “Golden Mountain”, named for the flecks of gold said to sparkle in its soil.

To villagers like Sai U, the mountain is more than a mineral deposit – it is sacred ground.

“We were told there was gold in the mountain, which is why it’s called that,” he said. “But we never searched for it. For us, the mountain is spiritual – our ancestors live there.”

But that reverence was not shared by outsiders. In 2007, the first four Chinese miners arrived with an official concession. They carved into the mountain’s slopes, removing its crest and leaving behind a lunar landscape.

“They first arrived without modern technology, so they simply blasted the whole mountain. Only recently did they acquire a mineral vein detector to drill specific areas,” said Sai U, who watched the mountain being destroyed with his fellow villagers.

As the excavations recently expanded to more than 20 mines – covering nearly 1,780 hectares, or five times the size of New York’s Central Park – Nam Kham turned dark and foul-smelling.

During heavy rain, the runoff from the mine surged downhill, flooding rice fields and homes, and contaminating the pond where the cattle drank.

It was then that Sai U first heard of cyanide – a hazardous chemical widely used in gold extraction.

Satellite imagery acquired by Mekong Eye and Dialogue Earth shows that none of the gold mining sites in Loi Kham or along the mountain ridge and rivers in eastern Shan State are equipped with proper cyanide storage or treatment facilities.

The images also reveal the risk of water leakage into several unnamed streams that flow three kilometers downhill into the transboundary Mekong River, as well as other international rivers.

The findings raise alarm over how unregulated mining in Myanmar’s uplands may be contaminating water sources far beyond its borders.

Deadly chemical

Since Myanmar’s 2021 military coup, unregulated gold mining has spread across the country – from Indawgyi Lake, a designated UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in the north, to the rivers inside the Tanintharyi Nature Reserve in the south – even encroaching on homes and farmlands of people displaced by the escalating civil war.

Gold miners usually use cyanide compounds as the primary chemical to extract gold from ore. This process, known as gold cyanidation, involves dissolving gold into a cyanide solution, leaving less valuable minerals behind.

Although there are several alternative compounds, such as thiosulphate, which is less toxic—cyanide solution remains widely used in gold mining due to its relatively low cost in extracting gold from ore. This makes it especially popular in unregulated and illegal mining operations.

In many low-grade gold mines, the cyanide solution is sprayed over heaps of ore, and the gold-laden liquid is collected in leaching ponds — often seen as rectangular marks on satellite images, such as those in eastern Shan State.

This process produces large volumes of cyanide-contaminated waste rock and liquid, which should be sent to tailings ponds for treatment. These ponds typically appear as large and deep, water-filled basins, covering at least one-third of the mining site.

However, in eastern Shan State, such tailings ponds are not visible on satellite images, raising a question about how the toxic waste is being managed.

A 2019 study conducted by academics from Taunggyi and Kyaing Tong Universities in Shan State tested soil samples from Mong Lin, a village only six kilometers from the Loi Kham mining area.

The results showed gold concentrations ranging from 0.12 to 1.89 parts per million (ppm) – meaning that only a fraction of a gram to nearly two grams of gold can be extracted from each ton of ore. This also means vast amounts of rock contaminated with cyanide are left behind.

Even at low concentrations, cyanide can interfere with cellular respiration, leading to rapid and potentially fatal effects.

While cyanide can break down in certain environments, it can remain hazardous for weeks to months without treatment, posing long-term risks to both ecosystems and human health.

Without proper containment measures – such as lined waste ponds or chemical treatment facilities – these toxic compounds can easily leak into the surrounding environment, contaminating soil, waterways and the food chain.

The risk is especially high during floods, which can carry toxic waste from mining sites into nearby villages—as experienced by residents of Na Hai Long village, located downhill from Loi Kham, during a major flood in 2022.

Gold mines in eastern Shan State are located in areas under the control of the United Wa State Army (UWSA), Asia’s most powerful non-state armed group, and two Lahu militias—both of which have been operating as border guard forces for the Myanmar military for more than two decades

The area remains largely inaccessible to journalists and independent researchers, making it nearly impossible to verify contamination through laboratory testing. Satellite imagery has become a key tool for identifying this toxic threat.

A threat to international rivers

Mining operations in eastern Shan State have been active along four international rivers — the Sai, Kok, Ruak, and Mekong Rivers — with many gold mines located just next to the Sai and the Mekong,

The Sai rivers are shared by Myanmar and Thailand, while the Mekong River feeds 70 million people in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam.

In Mong Len, more than 10 gold mines sit above unnamed streams that feed into the Mekong River.

Further southwest, the largest concentration of mines is found in Mong Kan village of Mong Ton township, where operations stretch along both banks of the Sai River for more than five kilometers.

Satellite imagery analyzed by Mekong Eye and Dialogue Earth revealed dozens of solution ponds scattered along the riverbanks, some less than 10 meters from the Sai River.

In Mae Jok village of Mong Hsat township — just five kilometers west of Mong Kan — one 24-hectare gold mine positioned less than 150 meters from Thailand’s border. It is operated over an unknown stream that is a tributary to the Sai.

The images were reviewed by two Thai mining and engineering experts, who spoke on condition of anonymity. They noted that the layout—particularly the altered landscape and the alignment of leaching ponds—is consistent with gold-processing operations. This was confirmed by accounts from villagers, who acknowledged the presence of the gold mine and the lack of proper tailings ponds.

Although the experts couldn’t confirm the exact extraction method, they stressed that gold cyanidation must be carried out on-site due to the dangers of transporting cyanide. “It’s too hazardous,” one expert explained. “A spill wouldn’t just release toxic chemicals—it could destroy the entire business.”

Downstream, Thai communities have begun to feel the impact. Villages in Mae Sai district, along the Sai River, reported murky water flooding their communities in September 2024.

Thailand’s Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency reviewed satellite images after the flood and identified mining in eastern Shan State as one of the causes, along with land use changes from deforestation and intensive agriculture.

Chaiyon Srisamut, 49, the mayor of Mae Sai Municipality, recalled how a historic flood nearly destroyed the northern Thai town. Residents had never witnessed such devastation – the river overflowed, carrying thick mud and debris.

“Officials on the Myanmar side consistently claim these areas are beyond their control, so they can’t intervene,” said Chaiyon, referring to the fact that mining areas were under the control of ethnic armed groups allied with the military.

The mayor cited water tests by local authorities, which later revealed traces of mining-related chemicals, including cyanide—though concentrations remained below official safety thresholds.

“I almost wish the levels had exceeded the limit,” he said, frustration evident in his voice. “Maybe then someone would be forced to take real action.”

As a local politician caught in a cross-border environmental crisis, Chaiyon says he feels powerless. Mae Sai must allocate a growing portion of its municipal budget to water treatment each year. The mayor has publicly urged residents not to swim or bathe in the Sai River.

“This is the best we can do,” he said.

Passive actions

The Responsible Gold Mining Principles call for the safe storage, treatment, and disposal of cyanide waste to minimize environmental harm.

For example, the well-known Thai-Australian Chatree gold mine at the border between Thailand’s Phichit and Phetchabun provinces spans nearly 600 hectares, with a tailings pond covering nearly one-third of the site.

According to the company, the tailings pond is designed to reduce cyanide concentrations in wastewater from 130 ppm to below 20 ppm – levels considered safe for environmental discharge.

Despite these mitigation measures, the Chatree mine faced repeated allegations of chemical leakage into surrounding communities, leading to court cases and a government-ordered shutdown that lasted six years.

At least four countries – Germany, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Costa Rica – have banned the use of cyanide leaching in gold mining altogether, citing the high risk of environmental contamination.

Since 2000, the global mining industry has adhered to the International Cyanide Management Code, a voluntary initiative designed to promote the safe and responsible handling of cyanide in gold mining.

Multiple requests to interview Nyi Rang, a spokesperson for the UWSA, about whether the code is implemented in territories under their control went unanswered.

Thanapon Piman, a senior research fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute, believes the international community should not wait for chemical concentrations to reach crisis levels before taking action.

“Detecting rising chemical levels could prompt downstream countries to respond,” he said. “These increases are evidence of what’s happening to the rivers.”

While the public often views cyanide pollution as less urgent than flash floods or mudslides, Thanapon warned that the two issues are deeply interconnected.

“When floods occur, river levels rise across the system – including areas near mines where leaching ponds sit along the banks,” he explained. “You can imagine what toxic substances those floodwaters might carry downstream.”

In January 2025, following a distinguished diplomatic career, Busadee Santipitaks was appointed Chief Executive Officer of the Mekong River Commission (MRC) Secretariat – the intergovernmental body tasked with managing the Mekong’s transboundary water resources.

Upon taking up that role, she emphasized that strengthening river monitoring would be one of her top priorities to better understand the region’s increasingly complex water dynamics.

When asked about the risk of cyanide contamination from gold mining operations in the Mekong Basin, the MRC Secretariat responded through a communications officer’s email that “we have no comment on the specific details of your findings.”

That reply came as no surprise to researchers at the Shan Human Rights Foundation, who have been documenting the harmful effects of gold mining in eastern Shan State for nearly a decade.

“We’ve raised this issue in several workshops attended by MRC representatives since our initial findings,” said a foundation spokesperson, who requested anonymity due to security concerns. “They had no response then, and they have no response now.”

Silence by fear

Mekong Eye and Dialogue Earth found it extremely difficult to persuade residents to speak about the mining’s impacts on their lives due to safety concerns.

In Sai U’s village, residents have been protesting against the mining operations since they started rapidly expanding two decades ago. However, the resistance was crushed in 2015 when a protester was shot dead, silencing the community through fear.

In Mong Kan, the fear of opposing the gold mining industry escalated after the UWSA arrived in 2001, forcibly displacing villagers to clear the way for mining operations.

“When we were forced to leave, our village headman tried to negotiate. He was detained, tortured and killed,” recalled Sai Som, 55, whose village now lies abandoned, with most of its residents scattered in displacement camps.

The lack of accountability surrounding extractive industries, including mining, has drawn international criticism.

In February 2024, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), a global coalition of 140 governments, companies and civil society organizations, delisted Myanmar, citing the country’s inability to uphold essential governance practices such as multi-stakeholder involvement and data transparency.

In the vacuum left by weak regulations and the ongoing conflict, Chinese miners have carved out a dominant presence in Myanmar’s gold-rich war zones, particularly along the porous border with China.

Their role is visible not only in the operation of mines, but also in the shadowy networks that move gold across borders. In one case, a Chinese national was arrested by Thai authorities after attempting to smuggle ten kilograms of gold bars – sourced from mines in Shan State – into Thailand without paying taxes.

China, the world’s largest gold producer with a 2023 output of nearly 380 metric tons, has long viewed foreign gold mining as a strategic asset – both to secure its domestic supply and to leverage geopolitical influence through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In 2024, metals and mining investments under the BRI reached a record US$21.4 billion, according to a report from the Griffith Asia Institute.

Countries such as Myanmar, Laos, Zimbabwe, Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo have become key destinations for Chinese mining investment.

China’s State Council Information Office (SCIO) released an article – citing multiple sources, including the China Gold Association – highlighting that outbound gold mining investments were key to increasing prosperity and boosting demand for gold and China’s gold trade with countries participating in the BRI.

However, multiple news reports indicate that these investments are often bundled in with infrastructure projects, debt agreements, and long-term trade arrangements.

While China’s gold reserves are extensive, the same SCIO report noted that the ore grade is “relatively low” and “some resources are not easily accessible.” This makes overseas ventures, where gold is richer and environmental regulations are lagging, an appealing alternative.

While Chinese mining operations are subject to strict regulations at home, Chinese-owned gold mines in countries as far away as Africa or as close as Indonesia – Southeast Asia’s largest gold producer – have faced legal consequences.

In contrast, no legal action has been taken against Chinese mining operations in Myanmar since the military coup of 2021.

The UWSA controls large stretches of gold-rich territory. The group functions as both a political buffer and an economic partner to Beijing.

Any disruption to mining operations under UWSA control risks drawing China further into the conflict—an outcome neither the Myanmar military nor the country’s patchwork of rebel groups is eager to provoke.

With limited international responses and continued silence within Myanmar, villagers like Sai U live in painful awareness of the destruction happening to their sacred mountain and golden river.

Meanwhile, those downstream remain largely unaware of the chemical “time bomb” slowly making its way toward them.

Note: All measurements of mines in Eastern Shan State were conducted using satellite imagery. For safety reasons, all names of individuals and locations in Eastern Shan State have been changed.

This story was supported by Earth Journalism Network, with Mekong Eye initiating and leading the investigation in collaboration with Dialogue Earth, Prachatai and Shan Herald Agency for News as co-publishers.

Read the story in Thai, Shan and Burmese.

Illustration by Paritta Wangkiat.