A major blackout in Phnom Penh and 24 provinces across the country on the night of November 26, 2015 became front-page headline news in Cambodia.

Tag: Environment

Harnessing Sesan River (Part 3): Living a new life in resettlement areas

For many of the 500 families in Srekor villages and six other villages in Stung Treng province of Cambodia, life will never be the same when they are moved to resettlement areas following the completion of the Sesan II dam.

Harnessing Sesan River (Part 2): Voices from another village facing evacuation to make way for a dam

Srekor village in Stung Treng province of Cambodia is another village destined to be evacuated to pave way for the construction of the lower Sesan II dam which is now 50 percent complete.

Harnessing Sesan River (Part 1): the choice between fish or electricity

“I can’t say whether fish and electricity can substitute each other…” so said Sana, a 25-year old fisherman of the Sesan river in Stung Treng province of Cambodia when asked by a Thai PBS reporter about the lower Sesan Dam II.

Harnessing the Sesan River: An In-depth look at the Lower Sesan 2 Dam

A comprehensive investigation into the myriad of social, economic and environmental challenges facing communities along one of the Mekong’s most biologically and socially vibrant tributaries due to the Cambodian government’s determination to erect a major hydroelectric dam.

Harnessing Sesan river (Part 6): Dam and fish in Samse river basin

The image of fishermen casting fish nets from their small wooden boats while others throwing bits of catfish meat into the river before using small baskets made of bamboo to catch small fish has been a commonplace in Jalai islet in mid Mekong river in Satung Treng province.

Jalai islet is about 25 kms from the lower Sesan II dam. This is the passageway of fish species that swim upstream from Tonle Sap and the lower Mekong river for spawning in the upper Mekong river and its tributaries which include Sekong, Seprok and Sesan which altogether form the Samse river basin.

Mekong dam a threat to rare dolphins – and villagers too

THE DON SAHONG hydroelectric dam threatens the last 80 Irrawaddy dolphins in the Mekong River – as well as the livelihoods of the people downstream in Cambodia, who depend heavily on the river’s resources.

The people in Preah Romkel village of Stung Treng province claim their way of life is in danger. The eco-tourism that boosts the local economy will be destroyed if the endangered Irrawaddy dolphins are driven into extinction by the impact of the new Don Sahong Dam on the Laos-Cambodian border.

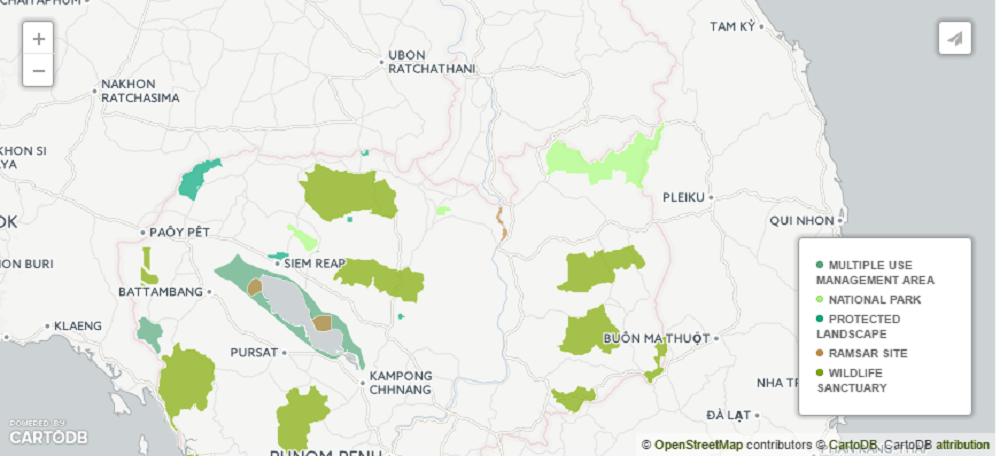

Government Will Start Chipping Away at Protected Areas

Between 2009 and 2012, the Ministry of Environment went on nationwide leasing spree, signing over vast swaths of the country’s nominally protected areas to private companies for rubber plantations and other agribusiness ventures.

In the name of jobs and development, the companies have cleared tens of thousands of hectares of forest in and around their economic land concessions (ELCs), giving Cambodia one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world. As a show of his efforts to rein in the more wayward ELCs, Prime Minister Hun Sen announced in February that the government had taken back nearly 1 million hectares, a little less than half of the area leased out nationwide.

Let there be light: The Challenge of powering Myanmar

Myanmar aims to achieve national electricity coverage by 2030, but there are big questions about whether that goal can be achieved and what impact it could have on the environment and communities.

Vietnam’s New Environmental Politics: A Fish out of Water?

The cross-country demonstrations currently taking place in Vietnam to protest massive fish die-offs along the central Vietnamese coast are truly remarkable. Not only were demonstrations at this scale unheard of even five years ago, but they beg the question of why thousands of demonstrators as far off as Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City are subjecting themselves to the threat of beating and arrest over dead fish in Central Vietnam.

Has a new environmental sensibility suddenly taken hold of the nation? Is it a rude awakening to the costs of decades of rapid industrialization and economic growth? Or is it simply a convenient expression of developmental malaise projected onto a foreign scapegoat, namely the Taiwanese Formosa Ha Tinh steel factory ,whose 1.8 km underground waste pipe is widely suspected as the principal cause of the die-off? Even as such sensibilities may be taking shape, they hardly explain the scale or intensity of the current confrontation.