The Yangtze River courses from the Himalayan Plateau in Tibet down into southwestern China’s Yunnan province, carving a path through a breathtaking landscape where steep ridges are covered in Yunnan pine. Closer to the river and the road that runs beside it, aspen and birch leaves shimmer in the wind. Clumps of pink rhododendron form natural fences along the terraces of corn, tobacco, and other crops that thrive in the rich soil created by millennia of flooding.

But this once-wild region is increasingly being tamed, and these days it echoes as much with the sounds of heavy machinery as it does with the rush of the river itself. A concrete and steel buttress to support a high-speed rail line from nearby Lijiang to the 11,000-foot mountain grasslands of Shangri-La slices across the sheer mountain slopes that ring the valley. A thousand feet below, an interstate highway is being built into these forested bluffs to speed tourists to Shangri-la and beyond. Far below on the valley floor, tunnels are being dug through the belly of the mountain and trenches plowed for pipes to divert the river’s sediment-laden waters to Honghe County, just south of the water-needy capital of Kunming.

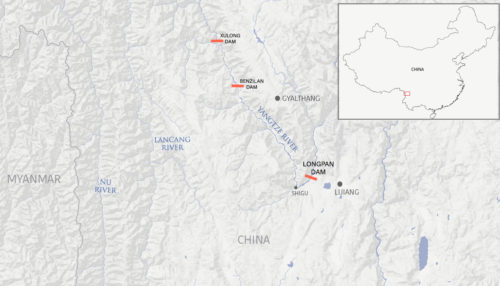

It is here, between where the Yangtze River turns abruptly at the town of Shigu and then roars through the World Heritage Site of Tiger Leaping Gorge, 30 miles to the north, that a controversial project that was declared dead a decade ago may now be coming back to life. And the expected revival of this major hydropower project is a symbol of just how much President Xi Jinping has tamed China’s once-robust environmental movement.

Fifteen years ago, local communities banded together with environmental activists to block construction of a dam — known as Tiger Leaping Gorge — that would have flooded villages along the Yangtze for 200 miles upstream. The campaign was one of the biggest success stories in China’s emerging environmental movement, preserving biodiversity in the valley and blocking the relocation of more than 100,000 people, including many Naxi and Tibetan minorities, whose homes would have been inundated. A documentary film, Waking the Green Tiger, followed campaigners who fought against the Tiger Leaping Gorge project, showing their elation upon hearing that then-Premier Wen Jiabao personally intervened to block the dam. The domestic and international media intensely covered the issue, some even encouraged by members of the central government.

The quiet re-emergence of the Longpan dam has not sparked the opposition it did 15 years ago.

That victory, which helped launch a wider environmental awakening in China, seems a lifetime away now. Today, a somewhat scaled-down version of the hydropower project — rebranded as Longpan, the town near where it is expected to be built — is again back on the table. Although the central government has not given final approval to the project, it appears in major planning documents, and environmental activists say that it is likely to be one of many major infrastructure initiatives being undertaken in western China, in part because Longpan’s reservoir could feed a water-diversion project already under construction in the region. In addition, a dam at Longpan would help reduce flooding downstream, an important consideration for China’s leaders after a summer of devastating floods hit the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze.

The quiet re-emergence of the Longpan dam has not sparked the opposition it did a decade-and-a-half ago. No local leaders have risen up to halt the project. No film crews, throngs of Chinese and foreign journalists, or domestic and international NGOs have descended on the valley to call attention to the dam’s threat to the local population and biodiversity.

That silence — amid the drone of jackhammers, diggers, and cranes busy constructing the valley’s railroad, highway, and water diversion projects — speaks volumes about how different the discussion surrounding the ecological and social impacts of China’s development have become under President Xi’s leadership. With a promise of creating an “ecological civilization,” Xi and the Communist Party have been able to reassert control of the environmental narrative.

The near-total control of the Party over discourse in the past few years, whether through social media or state-run media, coupled with increased restrictions on NGOs, has enabled the state to define what constitutes sustainable development. Now, environmental activism outside President Xi’s party lines can be hazardous to the health of NGOs and their leadership. In late September, in northwestern China, authorities arrested three environmental activists for allegedly using “violence, threats, insults, and intimidation to carry out illegal and criminal acts” as the men sought to protect gazelle habitat from the construction of wind energy projects.

If built, the Longpan dam is likely to be half the size of the original project, say environmentalists and former activists who spoke to Yale Environment 360 — on the condition of anonymity — during a recent trip there.

Yet even at half the size, the dam would have major impacts on aquatic populations already decimated by the 10 other existing dams on the Yangtze, as well as by dredging, pollution, and overfishing. As of 2019, another four dams were also under construction and at least 15 more — including the Longpan project — are in various states of planning. A 10-year commercial fishing ban was placed on the Yangtze at the start of 2020 due to the already dire situation.

Existing dams on the Yangtze have drastically altered the natural flows of the river and interfered with the migration and spawning of various species. Spawning grounds for Chinese hillstream loach, a fish endemic to the Yangtze that needs fast-moving water and gravelly river bottoms to thrive, has been severely impacted by the construction of the Liyuan hydropower project downstream from Tiger Leaping Gorge. Three other spawning grounds have been discovered in the area behind the proposed Longpan dam, including one directly at Longpan, according to earlier studies. Dams along the Yangtze also cause sedimentation and eutrophication within the reservoirs. And the power lines, roads, and other infrastructure associated with the dams fragment and degrade terrestrial habitats in the valleys.

Despite these cumulative impacts, Longpan recently appeared in a National Development and Reform Commission list of “green industry” projects approved and authorized for construction. “If the central government decides to invest heavily in infrastructure to rebuild the economy, then this project will be the first choice for Yunnan,” said a well-known conservationist during an interview last month.

Xi and the Party have embraced a theory of sustainable development known as the “Two Mountains” principle, based on the catchphrase, “Green waters and green mountains are gold mountains and silver mountains.” The slogan means, in effect, that China’s natural areas are to be protected since they are rich in natural resources, but could be exploited if needed. This guiding principle has as much to do with continued exploitation of resources as it does protecting them. The key is that the Party decides — not grassroots environmental activists, and not villagers who are in the way of economic development projects.

The catchphrase has successfully co-opted grassroots environmental campaigns like the ones that stopped Tiger Leaping Gorge dam and dams on the nearby Nu River, the last free-flowing river in China. Many environmental NGOs are being sidelined due to policies that require them to be sponsored by government institutions. And international NGOs, which were helpful in magnifying the work of those domestic organizations, have been effectively silenced under the country’s Foreign NGO Law. Enacted in 2017, the law requires international organizations to register with provincial or national security bureaus and to be affiliated with a domestic institution.

As for the reborn Longpan dam, there is little public discussion about when the project will commence or where exactly it will be built. No one refers to it as Tiger Leaping Gorge dam anymore, and even mention of the Longpan dam in the media is generally curtailed. “There are still people in those villages who want to fight, but they lack leadership and no one wants to become the leader,” a former well-known Chinese NGO head told me.

“There’s not much we as environmentalists can do now — you’ll get yourself into trouble if you try.”

One conservationist, who ran a Chinese NGO that was recently shut down, said the dam is expected to flood villages as far upstream as 100 miles. One former village activist in the town of Jinjiang, which would likely be inundated, said he expects the hydropower project will move forward because powerful economic and political forces will swamp the scattered opposition from villagers and environmental activists. “There are so many companies and interest groups that possess the necessary resources and massive support from various parties,” said the conservationist, who asked not to be identified. “Environmental NGOs and community activists appear helpless in the face of these interest groups.”

The activists all said that the elevation of Xi’s “Two Mountains” slogan and the narrowing of open discussion mean there is little room for grassroots efforts. “There’s not much we as environmentalists can do now,” the Jinjiang activist said. “You’ll get yourself into trouble if you try.”

He and others said that once-strong and vocal support among youth in opposition to hydropower dams and other projects has also eroded in the region. “There are changing views among the younger generation,” he said. “Most younger people do care about the [Longpan] dam, but they are not as attached to the land as we are, since most of them now work in cities far away. And older die-hard opponents of the project are dying away.”

The transformation of Yunnan province by major infrastructure projects is part of a Communist Party effort to reduce poverty and establish large energy bases in the western part of the country. The latter would combine hydropower with nearby solar and wind projects to help counter intermittent energy generation. Other projects include pumped storage of water to power hydroelectric turbines and the diversion of water to areas where it is needed.

For example, the Dianzhong Water Diversion Project — 400 miles of pipes, mostly tunneled through the mountains — will use a series of pumping stations to divert waters from Shigu southeastward to Dali and eventually terminating near Kunming. That project is now under construction and, once completed, would create the need for a reservoir at a certain height to sustain water flow through the system. That will likely be an important rationale for Longpan dam, NGO officials said.

The most recent sign that planners could be gearing up to build Longpan was the purchase earlier this year of a 23 percent share of the company owning the rights to build the dam by China Yangtze Power, the main subsidiary of the company that operates the massive Three Gorges Dam.

Farther north and upstream from the potential Longpan site, two other dams are in various states of approval — Xulong, which has reportedly completed an environmental impact assessment, and Benzilan, near Shangri-la, which could get approval next. Along with Longpan, these could form a cascade of dams in that section of the Yangtze to regulate water and divert it to Dali and Kunming.

While the planned dams may now appear unneeded, China’s leadership believes they will be viable in the near future.

All of these projects run close to UNESCO World Heritage sites and buffer zones.

These designations were made to protect the biodiversity of the Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage Site, which includes the upper reaches of the Yangtze, Nu [Salween]. and Lancang [Mekong] rivers, encompassing an area larger than Yellowstone National Park. Yet in practice, the boundaries of the protected areas, created in 2003, were only for the heights above the rivers and not habitats within their valleys, leaving the waterways and the communities along them exposed to development. Last year, UNESCO warned of “major changes of aquatic systems” if more hydropower projects are constructed along the rivers.

Because it would reflect poorly on China’s efforts to preserve biodiversity, it is unlikely that the government would announce anything regarding the construction of Longpan before the United Nations Biodiversity Summit, which was supposed to be held in Kunming in October 2020 but has been postponed to May of next year.

While hydropower generated in Southwest China is often wasted, government officials hope that with better connections among electricity grids, excess power will be transmitted to more populous areas in eastern China, as well as to Southeast Asia. So while the Longpan, Xulong, and Benzilian dams may appear unneeded at the moment, China’s leadership believes they will be viable in the near future. Still, experts say that with the rise of wind and solar generation in China, the country’s embrace of hydropower will inevitably fade.

“It seems increasingly likely these dams will be among the last, as China loosens its decade-long fixation on hydro,” said Gabriel Lafitte, an author and development consultant long focused on environmental issues in the Tibetan areas of southwestern China.

That vision is not likely to comfort those older villagers living along the upper Yangtze who may eventually have to relocate.

According to the former activist in Jinjiang, the most recent calculation for compensation for flooded land and relocation would be a maximum of 200,000 yuan per person, or nearly $30,000. Previous calculations a decade before were only 40,000 yuan per household, or around $6,000. Those larger payouts may eventually split families by appealing to youth, many of whom have already gone to work in urban areas.

Said one activist, “That amount won’t buy the hearts of the [older] villagers, because of inflation and our attachment to the land.”

This story was originally published on Yale Environment 360 on 5 October 2020. It was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

This story was originally published on Yale Environment 360. It was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

Michael Standaert is a freelance journalist based in South China and primarily covering environment, energy and climate change policy for Bloomberg Environment. He also contributes to other publications such as The Guardian, Al Jazeera, and MIT Technology Review. He has resided in China since 2007.