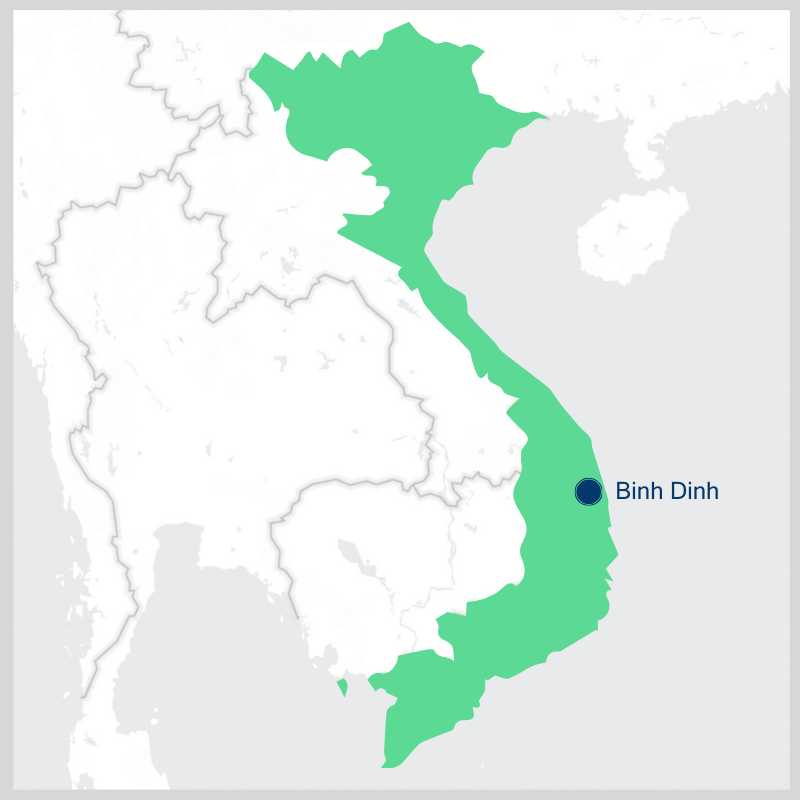

BINH DINH, CENTRAL VIETNAM ― Vietnam has supplied wood pellets to Japan and South Korea in their quest to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions through an increase in biomass energy production. However, the origins of these pellets are questionable, and some are even linked to deforestation.

When the rainy season begins in September, mountains throughout Central Vietnam are covered with an infinite expanse of green. Yet the green is not of natural forests made up of native tree species.

The forests are actually plantations of exotic acacia trees, and they are a sign of massive deforestation.

Hai, a 40-year-old farmer in the country’s central Binh Dinh province, cleared the natural forests a decade ago amid the villagers’ rush to plant acacia ― the raw material used for producing wood pellets currently being marketed as an environmentally friendly and low-cost energy source.

Part of his two-hectare hilly plantation is located in the ‘production forest area,’ the state land distributed to villagers for growing commercial timber trees nearly 20 years ago. He obtained another “very small” part of the plantation through forest clearance.

“Back then, many people here did the same [by clearing natural forest for acacia plantations]” said Hai.

It took five years for his farm to yield fruit. This past summer, he managed to sell 60 tons of acacia wood from the entire plantation to a local trader for VND 1.2 million per ton (or nearly $US 50 per ton).

The ivory-white woods are loaded onto trucks, carried along a mountainside road, and arrive at a wood chip factory called Hung Nguyet Anh, not far from Hai’s plantation.

Fresh logs, the faint fragrance of which still wafts around after being cut, are picked up by a crane and put into a machine where they are chopped into chips ― ready to be used as fuel or raw material for industrial wood pellets.

Hung Nguyet Anh presents itself as a company specializing in wood chip production. In 2021, the government of Van Canh district in Binh Dinh province posted an announcement on its website approving the company’s pellet factory project.

Woody biomass–namely wood pellets and chips, along with non-woody agricultural residue–can be classified as a renewable source of energy when burned.

The logic behind considering them as such is that while fossil fuels require millions of years to be formed before they are combusted, biomass fuels can be regrown after being cut and burned in quick succession.

This maintains carbon in trees and soil in theory, and prevents far fewer harmful greenhouse gas emissions from entering the atmosphere.

Both United Nations and EU policies that consider woody biomass as carbon neutral, encourage countries to convert their coal-fired power plants to instead burn biomass.

The solution is very appealing to many countries because it’s less expensive than installing wind and solar power plants but still allows them to meet their greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets.

Woody biomass energy is therefore marketed as a “net-zero” solution with a bargain price tag, although it occasionally receives bad press and criticism from scientists.

The global system for accounting for emissions since the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and countries’ national climate policies do “not count CO2 emitted from tailpipes and smokestacks when bioenergy is being used.” As a result, wood burning is rising worldwide, and in Asia, Japan and South Korea are leading the way.

According to Vietnamese customs data obtained through a business information service, Hung Nguyet Anh exported wood pellets to Japan-based Mitsui & Co, one of the country’s largest trading companies under the Mitsui Group.

The company’s 2023 report states that it generates 27% of its profit from energy with plans to increase renewables in its business portfolio to over 30% by 2030. Currently, it operates a biomass energy plant in Tomakomai City, Hokkaido.

The report does not identify the sources of materials used in the plant. However, it signals that demand for Vietnamese wood pellets exists in Japan, and this is not limited to one company or one country.

From 2013 to 2022, the export volume of Vietnamese pellets went up 28 times, and the export value skyrocketed 34 times. The material brought the country nearly US$790 million in export turnover in 2022.

It’s expected that the wood pellet industry will have an export turnover of over US$1 billion in the future, especially when European nations ― the potential export market for Vietnam ― begin to count wood products and other biomass as carbon neutral. Several other countries are also weighing up the future of biomass fuels as a renewable energy source.

However, the production of wood pellets is not as clean as importers claim. The farmer Hai witnesses the deforestation of natural areas in his village, and none of the traders ask him or other farmers about the origin of acacia trees.

“If I sell them less than 100 tons at a time, I don’t have to show any documents. When I buy acacia, I don’t ask them [farmers] if the land where they grow the trees is recognized as production forest by the state or not,” said So, a farmer and a trader in Binh Dinh.

Hung Nguyet Anh only asked for an acacia land certificate if he brought a quantity of several hundred tons of wood.

“We are all poor farmers, if those matters are questioned, no one can sell acacia wood.”

Appetite for wood-burning

Wood pellet products receive certain privileges from the Vietnamese government, which relaxes supervision of production and export processes. The Deputy Director General of the General Department of Forestry admitted in a conference last year that “the origin of [pellets’] raw materials has not been controlled.”

By assuming that pellets are processed from small wood waste and residues like branches and chips in the agricultural and wood industries, export businesses are not required to declare the type of wood being sourced. Export taxes are also exempted for these products.

Last year, the Vietnam Timber and Forest Products Association (Viforest) and the Vietnam General Department of Forestry opposed the government tax consulting agency’s proposal to apply this tax on such products.

As a result, Vietnamese pellets become even more attractive, especially to Asian markets that are not strict about the provenance of imported raw materials. Viforest did not respond to the reporter’s request for comment.

Japan and South Korea account for nearly 100% of the total volume and value of Vietnam’s pellet exports from 2019 to the present date.

Both countries have pledged to accelerate renewable energy and reach ‘net-zero’ targets by 2050, and they are looking at biomass as an indispensable component of the energy transition despite limited sources of domestic wood.

The drive for long-term energy security has been fierce in Japan in the wake of the 2011 tsunami and subsequent Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima nuclear accident.

Meanwhile, the appetite for woody-burning has grown exponentially in Japan and South Korea in the past decade due to heavy subsidies for wood sourcing and a biomass feed-in-tariff that have lured in more investors to the sector.

“The boom in building biomass power plants in Japan was primarily driven by the feed-in tariff, which, at its peak in the period 2016-2019, was the highest incentive for wood biomass in the world at ¥24 (then US$0.20) per kilowatt-hour”, said Roger Smith, Japan Director at Mighty Earth, whose work focuses on supporting Japan’s clean energy transition and helping companies achieve deforestation-free supply chains.

In South Korea, according to the Seoul-based non-profit organization Solution For Our Climate (SFOC), biomass is the most heavily incentivized form of renewable energy in the country, receiving policy subsidies greater than those for solar.

Much like South Korea, Japan does not have enough domestic material to feed all its power plants. Cedar trees have been harvested but logging activities cannot be carried out year-round, as it takes decades for the trees to attain a size suitable for biofuel. Moreover, cutting trees during snowy winters is unfeasible due to safety concerns, especially in high-elevation mountainous regions.

This has made Vietnamese wood pellets attractive for biomass expansion due to their economical price, as well as geographic proximity and close economic ties between Vietnam and the two East Asian nations.

As reported in the South Korean Forestry Department‘s 2021 wood use survey, 78.5% of wood pellets distributed in South Korea were imported. Of these, 62.6% were from Vietnam.

Japan’s trade statistics show that around 30% of fuel input for biomass power generation is currently supplied by imported wood pellets and chips. Vietnam is the country’s second-largest supplier of wood pellets, while Japan is the second-largest customer of Vietnamese wood chips after China.

Vietnam even has the potential to surpass the world’s major wood pellets exporter Canada. A study by the Central Electricity Industry Research Institute and Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology indicated that using pellets produced in Vietnam is more economical than those produced in the Northern American country because of the competitive price.

Unknown origin

The US-based non-profit organization Forest Trend reported that domestically grown acacia accounted for 70% of the proportion of wood species used as the raw material for pellets 2021.

Acacia also dominates Vietnam’s wood-pelleted production sector. But of the total 2.35 million hectares of acacia Vietnam planted by 2020, only 15% have achieved Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification ― which signifies that the material has been sourced from responsibly managed forests.

Only a few Japanese importers require pellets from Vietnam to have FSC certificates. Not a single South Korean firm does.

Additionally, only a restricted number of plantation areas are certified by both national and international certifiers. This is the case with the VSFC/PEFC certification scheme, which is a collaboration between the Vietnam Sustainable Forest Certificate (VSFC) and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC).

Based on data from September 2022, the same report points out that there were several pellet factories in Central Vietnam that used materials originating from natural forests.

In other provinces, most traders, truck drivers, and farmers interviewed said that factories do not question them about the origin of the acacia wood they deliver.

“What the factory cares about is whether the acacia trees reach five years of maturity, whether the diameter is over six centimeters, and whether the tree trunk is dry. No one asks where they are grown,” said Tu, a farmer and acacia trader in Dak Lak of Vietnam’s Central Highlands.

Tu often sells acacia wood to a factory named Nam Van Phong in Ninh Thuan province.

In a phone interview, the Deputy Director of the company, Vu Ngoc Su, stated, “the forests that the company purchases are all FSC certified.”

According to Vietnam Customs data obtained through a business information service, Nam Van Phong’s customer is ITOCHU, a corporation that supplies wood pellets to many biomass energy plants in Japan, including Hyuga Biomass Power in Osaka and Tahara Green Biomass in Tokyo.

ITOCHU announced in its 2023 annual report that it had completely withdrawn from thermal coal interests during its current mid-term management plan period.

The company imports about 500,000 tons of pellets from Vietnam every year, of which 300,000 tons are from Binh Dinh. It also revealed a plan to plant a timber forest and build a wood pellet production factory in Central Vietnam.

The Vietnamese customs data also reveal that one of ITOCHU’s pellet suppliers in Vietnam is Asia’s biggest wood pellet producer An Viet Phat Energy, which was blocked by FSC last year for deliberately making false claims about a large volume of wood pellets sold in 2020.

The company created purchase documents with all the materials used in products bearing the FSC label, although it also used wood harvested in non-FSC forests. The Forest Stewardship Council confirmed via email that it has not yet unblocked An Viet Phat.

An Viet Phat Energy is also one of the four largest pellet suppliers to South Korea. A 2022 report by Advocates for Public Interest Law says the company’s clients include SGC Energy, Emerging Global, Hyundai Rivat, GS Global, and Samsung C&T ― some of which directly operate biomass power plants.

An investigation by the Korean Center for Investigative Journalism Newstapa showed Samsung C&T provided about 95,000 tons of wood pellets produced by An Viet Phat Energy to four public South Korean power generation companies ― Nambu, Southeast, Western and Korea Midland Power ― from 2019 to 2022.

South Korea has established a legal standard for importing timber products, but this regulation only verifies legality and does not address sustainability or environmental impact. According to SFOC, as long as the products are considered legal in the producer country like in Vietnam, South Korea sees no trouble in importing them.

“The South Korea Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) so far has overlooked the sustainability of woody burning. There’s a lot of lobbying, cartel and dirty businesses happening in Korea, especially around the forestry sector”, said Hansae Song, Bioenergy & Land Use Program Officer of SFOC . “The MOTIE didn’t want to deal with this, but now it is facing mounting pressure in Korea.”

An Viet Phat Energy has been criticized for its level of commitment to ensuring environmental safety in its production activities. One of its factories, located in Phu Tho province, 100 kilometers northwest of Hanoi, has been accused by local people of causing air and water pollution.

In 2021, this factory was fined VND 35 million (about US$1,400) and had its operations suspended due to violations of Vietnamese environmental law. But the factory has continued its operation while the pollution it caused has not been resolved.

Despite the controversy, An Viet Phat Energy continues to operate and will in fact and expand its production scale to a total of 10 pellet factories. One of these received a loan from the state-owned Joint Stock Commercial Bank for Investment and Development of Vietnam.

In a phone interview, CEO Andy Bui affirmed that Japanese and South Korean companies continue to purchase wood pellets produced by the company.

“We possess records validating the origin of raw materials used in wood pellet production. Specifically for the Japanese market, our products hold VFSC/PEFC” said Bui.

Roger Smith from the Mighty Earth believes that other companies are likely engaging in similar practices as An Viet Phat Energy.

“The issue here lies on the Japanese side. They are supposed to demonstrate that the production was conducted legally, but they don’t thoroughly check in any meaningful way”, Smith added.

Ensure traceability

Vietnam-based companies like Nam Van Phong, Hung Nguyen Anh, and Hao Hung are said to hold FSC certification.

For many years, Chinese company Hao Hung has been one of the familiar names among the traders in Vietnam’s Central region, which has turned into an acacia-growing hub.

The company’s main production and business sectors include wood pellets and chips that are exported around the world, according to information provided on its website.

Since this summer, its subsidiary in Quang Nam province, named Hoang Ngan Quang Nam, has changed its material input purchasing strategy to ensure its product quality follows the requirements of its Japanese customers.

“In the past, they bought all types of wood, regardless of sizes, including scrap branches,” said Nham, a 30-year-old acacia supplier to the Chinese company for the past six years.

“But now the selection is stricter, only acacia trunks with a diameter of six centimeters or more are selected, and small branches and crowns are returned.”

Hoang Ngan Quang Nam has required drivers delivering acacia wood to fill out a “Forest Product Declaration Form” that clarifies the full name and phone number of acacia growers, buyers, and transporters, as well as the origin, dimensions, and wood species involved.

Starting from February this year, the completion of the form is required under Vietnam’s Forestry Law when parties buy and sell industrial timber. It’s part of the Vietnamese government’s effort to ensure the management and traceability of forest products.

However, Nham confirmed that the factories will unlikely investigate further if the information provided on the form is falsified.

“If the declared information of the grower is falsified, I guess they [the factory staff] will not know,” he said.

On numerous occasions, he has witnessed the acacia wood he transports to Hoang Ngan Quang Nam’s factory being sourced from natural forests on the mountaintop, where local farmers clear land to scrape by. And in so doing, apparently, answer the call for a clean energy transition.

Note: For personal safety reasons, the farmers, traders, and drivers are referred to by their first names.

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network for the “It’s a Wash” collaborative reporting project and RIN. It’s the first part of a series investigating Vietnam’s wood pellet industry and its impact on the environment. Find the second part here.

Vo Kieu Bao Uyen is a Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN) Fellow.

Thanh Nguyen is a Ho Chi Minh-based photojournalist and photo editor. In the last decade, Thanh has dedicated himself to documenting the profound impact of climate change on people, culture, and the environment throughout Vietnam.