LÂM ĐỒNG, VIỆT NAM – It only takes a glance to see where Bùi Tuấn’s food forest ends and his neighbors’ coffee farms begin. Lush thickets of trees are abruptly cut off by bare ground dotted with neat rows of small coffee trees.

In Viet Nam’s Central Highlands, the dry gusts of wind and searing heat stop at the sanctuary’s borders, marked by towering macadamia and kassod trees. In their shade, coffee and about 100 kinds of fruit trees, herbs and vegetables quietly thrive.

Strolling through the food forest is a visual and gastronomical delight, with dragon fruit vines draping the trail, mulberries flaunting their hues and mint leaves exuding a tangy aroma.

“A food forest mimics the structure of a forest,” 38-year-old Tuấn told Mekong Eye. “It provides food for humans while balancing the ecosystem,” he added. His 2.7-hectare garden feeds and provides livelihoods for his entire family of five, except for things it can’t produce such as spices, rice and seafood.

Former human resource specialist Tuấn is part of a budding community of farmers in Viet Nam who are rethinking their relationship with nature and forging their own paths outside the mainstream food systems discourse. Inspired by permaculture and other agroecological practices, they shift the conventional focus on yield to soil regeneration, from reliance on external synthetic inputs to circularity.

Thousands of Vietnamese farmers, including approximately 58,000 members of the Facebook group Trồng rừng trong vườn (forest gardening), have been inspired by the concept. Tuấn said most food forests he has encountered in Viet Nam are in their early stages. His is in its seventh year.

Gauging the true scale of food forests in Viet Nam is challenging due to a lack of official data. However, agroforestry, a broader concept of integrated tree-crops-animals farming, was estimated to have a modest cover of 900,000 hectares nationwide in 2014, according to the International Centre for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF) in Viet Nam.

Mental and ecological repairs

For 15 years, neat rows of Robusta coffee trees sprayed with pesticides and fertilized with synthetic NPK gave Tuấn’s family a steady annual yield of 6-7 tons.

Tuấn quit his HR job and took over the farm in 2014. Three years in, he realized three casualties of intensive monoculture: soil health, his children’s future and his mental wellbeing.

“If we don’t regenerate the soil, the following generations won’t be able to cultivate anything. Is the land we leave behind wealth or a burden?” he asked.

“It [intensive farming] stressed me out. Imagine pruning or weeding thousands of trees. Of course, people have to resort to chemicals to save time, and in return they degrade the soil,” he said, recalling the old days.

Tuấn’s parents, like the majority of farmers in Viet Nam, embraced intensive monoculture farming following national policies aimed at increasing yields for export and food security after the state subsidy period (Đổi Mới) ended in 1986.

In the past four decades, Viet Nam has become a leading producer of rice and coffee, yet agricultural land has been severely degraded, largely due to industrial, chemical-heavy practices.

Tuấn discovered alternatives. A game changer, he recalled, was reading Masanobu Fukuoka’s One Straw Revolution and Takuji Ishikawa’s Miracle Apples, both of which advocate for chemical-free farming.

“I care deeply about the soil. Why does it gift us flowers and fruit, only for us to mistreat it so?” he pondered, carefully navigating through thick grass, bushes and felled banana tree trunks.

Other food forest farmers Mekong Eye spoke to also credit their bond with nature as the key catalyst for change.

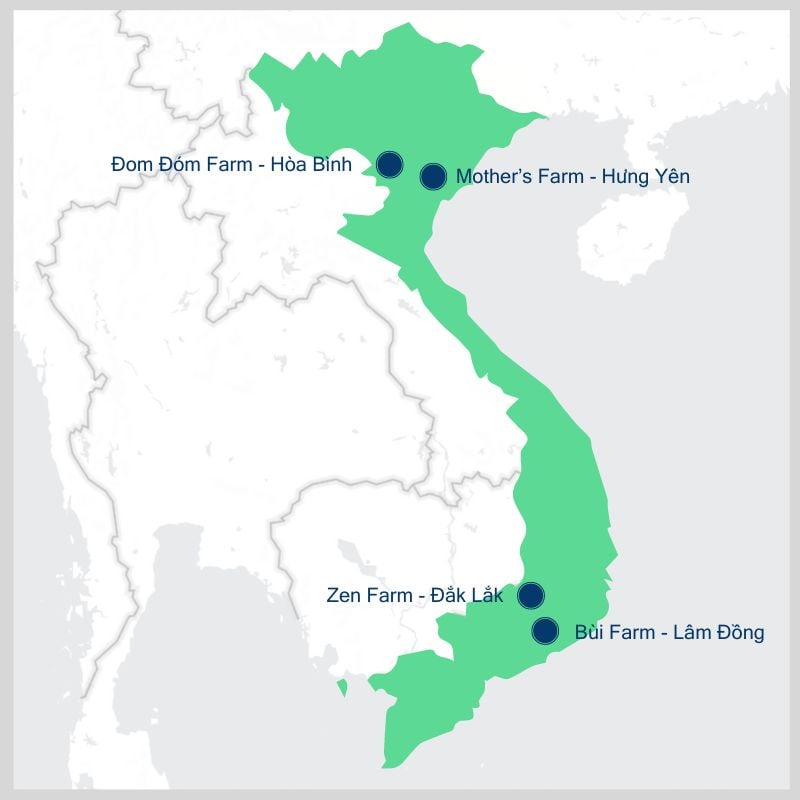

Henry Herbert of Đom Đóm Farm spent years backpacking and living on permaculture farms around the world before starting his own food forest to satisfy his fascination with nature. Nguyễn Tất Hoàng, the owner of Mother’s Farm in Hưng Yên, studied the ecological impacts of chemicals in university and was determined to undo their harm after earning his degree in petrochemical engineering.

Trang, who started the ZeN Farm in Đắk Lắk, thinks of nature as a sanctuary for human wellbeing and in nurturing the soil, she finds solace and healing.

“It’s like a dance. You dance with nature when you farm,” Herbert told Mekong Eye as he walked us through his newly established food forest in Hòa Bình.

It takes careful planning to dance well with nature, however. Food forest farmers draw from a large body of literature, among them permaculture, agroforestry and natural farming. The overarching goal is ubiquitous: mimicking nature to create a diverse, long lasting and self-sufficient ecosystem.

First, a food forest is built to last. Like a forest, the garden consists of mostly, if not all, perennial plants.

Second, it mimics a forest’s structure by having diverse plant layers, each serving an ecological function.

In Tuấn’s garden, Western soapberry, macadamia and kassod trees form the canopy, filtering sunlight and shielding the lower layers from the harsh winds and sun. Their strong root systems retain water and aerate the soil.

The shrub layer contains shade-loving crops like coffee and banana. Grass and herbs such as artichoke, mint and chili populate the ground. Underneath the herbs, root crops like turmeric, arrowroot and ginger prevent topsoil erosion during heavy rain.

Dragon fruit vines scale avocado branches and soon pepper vines will climb Indian trumpet trees. Several individual species, such as river tamarind and perennial peanut, are nitrogen-fixing, meaning they are able to convert nutrients into a form plants can uptake, thereby enriching the soil, improving yields and reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

Third, the food forest emulates the circularity found in nature. A species’ output is another’s input, effectively closing the loop. For example, Tuấn and Trang use cow’s manure to fertilize their coffee trees.

Hoàng makes fertilizer from the water hyacinth he grows in his irrigation canal. Both Tuấn and Herbert fell banana trees and lay the trunks around crop bushes to let them naturally decompose and regulate the soil temperature.

Absolute circularity is difficult to achieve, but food forest farmers try to minimize any reliance on external inputs and prioritize local sourcing whenever possible. Hoàng supplements his homemade fertilizer with fish manure from nearby farms, while Herbert gathers leaf mold from the nearby forest, which is rich in indigenous micro-organisms for his compost and mulch.

These concepts are not entirely novel to Vietnamese farmers. In the 1980s, the government introduced and popularized a form of integrated farming known as VAC (Vườn-Ao-Chuồng), combining gardens, ponds and barns.

Before the Green Revolution reached the country, farmers mainly practiced extensive agriculture, with minimal labor, fertilizers or capital inputs. Hoang has fond memories of how his grandfather intermingled various fruit trees in his orchard without the need for pesticides.

Quitting chemicals

Reversing decades of nutrient depletion and chemical build-up in soil is no easy task. The first three to five years are often the most challenging, farmers say, as the abrupt removal of chemicals inevitably drops yield and invites pests.

Tuấn’s coffee yield nearly halved the first year he quit using chemical fertilizers.

“My parents didn’t say much, but I know they were very sad,” he recalled.

Hoàng battled with pests in the farm’s second year. His mother still remembers plucking worms by hand from their sapodilla trees.

Herbert and his wife, Linh, however, see pests and low yields as a matter of course during the soil recovery period.

“We just realized that this year it is impossible to make the trees produce as much good fruit and perfect fruit as possible, so we accept sharing some with the insects,” said Linh.

Additionally, yields are not an accurate parameter for their garden’s success, Herbert says. Minimal input, a diversification of output and, most importantly, the ecological value of soil regeneration needs to be accounted for.

“We have become almost addicted to the fossil fuel industry and the production of chemical fertilizers, and that has warped our expectations of what we should be getting,” said Herbert.

Trang isn’t worried either. Biodiversity makes coffee less of a target for pests, which affect only about 0.1% of her yield. Pests are also no longer a concern for Tuấn. He focuses on strengthening the health of each tree, so they can defend themselves against pests.

It gets better financially too. While Herbert, Linh and Hoàng are still working towards financial independence, Trang and Tuấn have been able to stand on their own feet. Trang’s Zen farm started generating income from the third year, and she expects to break even in two years. Her ecological coffee now sells at 40% higher than the average price.

Tuấn’s income has steadily risen by about 15% since transitioning in 2017. Instead of selling raw produce, his family opted for processed fruit such as ground coffee and banana chips. In 2023, they made a profit of about 400 million VND (US$15,700), a significant increase from the 30-40 million VND ($1,200-1500) average annual profit made during intensive farming.

His food forest has also proven to be more resilient as the climate harshens. Although he has not seen rain in the past six months and shares his neighbors’ struggle to irrigate their coffee, the farm still earns a regular income from bananas and other produce.

“The more we give back to the land than what we take away, the more resilient the land becomes, and the more sustainable the garden is,” Tuấn said.

“If we take away too much, the garden will degrade, and our job will be much harder in the future,” he added.

Tuấn’s family support has solidified over the years. His parents now find joy in nurturing saplings of every kind, not only coffee.

“Without my family, none of this would be possible,” Tuấn said.

The way forward

Seven years into the transition, coffee farmers in Lâm Đồng province know Tuấn’s food forest coffee sells for a higher price, yet few have decided to change their ways.

“They say they are constrained by many things, like debts to distributors, for example,” Tuấn said. “They are afraid they won’t have an income for several years, and I can’t guarantee that their food forests will come to fruition like mine.”

Tuấn and Herbert now focus solely on farmers who recognize soil degradation as a problem and are eager to find solutions.

ICRAF Viet Nam country coordinator and senior scientist Nguyễn Quang Tân, who has been involved in agroforestry for more than two decades, noted that there are now more farmers and government officials with such awareness than there were in the 1990s.

Yet he says many still face obstacles when transitioning away from intensive farming, and scaling up integrated models like agroforestry will not be easy.

First, the upfront investment for agroforestry is high. Most farmers have limited capital and usually can’t afford to invest in several crops at once.

Second, farmers and agricultural specialists are typically trained with a species-based mindset rather than an integrated, systems-based approach. Introducing integrated farming models like agroforestry therefore requires extensive training to foster a cognitive shift.

Thirdly, scaling up agroforestry requires coordinated planning and infrastructure to facilitate sales of the output. Farmers must be equipped with the business acumen to process raw fruit, for example.

Tân believes that a national strategy is necessary to gradually shift the paradigm toward more integrated farming systems. In the meantime, pioneers such as food forest farmers play a crucial role in initiating change.

“If you want to scale up, you need to support pioneer farmers who are willing to try agroforestry first. After that, you will need a cohort of followers to go beyond the trials,” he noted.

It’s also important to start early. Herbert is helping schools in Hanoi set up their gardens, while educating children about the planet and its limits.

“Growing food and connecting with nature should start from a young age. It should not just be farmers’ concerns,” said Herbert.