BALI, INDONESIA – At the World Water Forum in Bali last week, the Mekong region was highlighted as a model of successful transboundary water cooperation. However, local communities emphasized that achieving meaningful cooperation on all levels remains an ongoing challenge.

Anoulak Kittikhoun, the Chief Executive Officer of the Mekong River Commission (MRC) secretariat, was seen actively participating in various panel discussions at the 10th World Water Forum to share lessons learned from his region.

“The Mekong is classified as the great world river, so many interested parties from all over the world are interested in what we are doing in the Mekong and how the MRC supports member countries for cooperation,” Anoulak told the forum.

“We shared lessons learned in different panels, not only from the MRC secretariat, but also from the MRC country representatives, like stakeholder engagement, river monitoring technology, forecasting, cooperation in data sharing and implementation of procedures.”

Held every three years, the World Water Forum 2024 was spearheaded by the World Water Council and the Indonesian government, which brought together 50,000 participants from more than 160 countries.

For more than a week, thematic panel discussions and open and closed-door meetings on water challenges and solutions were organized at many levels by ministers, governmental officials, donors, academics and the private sector, although the small presence of civil society groups and communities was due to the pricey entrance fee.

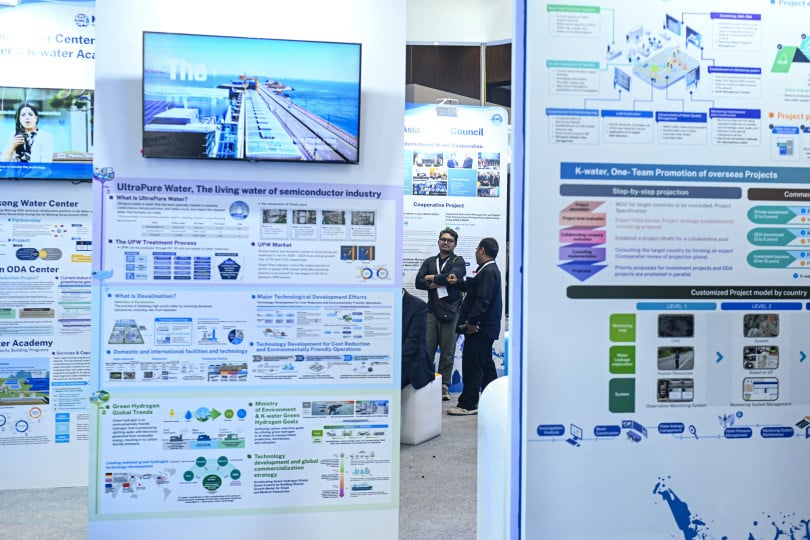

Technology and water solutions were showcased at the expo with gray infrastructure, traditionally engineered structures like dams and canals were heavily presented, along with other technology like smart agriculture, a digital twin for water management, and early warning systems.

Although criticized for being corporate-driven, with SpaceX CEO Elon Musk giving an opening speech while more than 110 water project deals were agreed or discussed, the forum lived up to its commitment to address the many critical water and climate issues.

Among these was transboundary water governance, which was highlighted in many panel discussions joined by MRC representatives and governmental officials from Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam.

Cooperation lagging behind

Ensuring transboundary water cooperation was one of the Sustainable Development Goals to be achieved by 2030.

This cooperation can take the form of a joint body to manage shared water resources, regular and formal communication, and data sharing among riparian countries, as well as the implementation of joint or coordinated management plans.

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe reported that, as of 2023, transboundary water cooperation was still lagging globally.

Only 43 of more than 120 countries have operational arrangements in place for 90% or more of their waters, prompting Secretary of the Water Convention Sonja Koeppel to call for global acceleration in this area during the Bali meeting.

For Asia, 25 of 30 countries share transboundary rivers, lakes and aquifers. Only six countries – including Cambodia, Laos and Thailand – have operational arrangements in place.

The Mekong region stands out in this area as it achieved the signing of the 1995 Mekong Agreement and co-established the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation deal with China in 2016.

Both multilateral mechanisms facilitate collaboration and dialogue among six countries sharing the 4,900-kilometer Mekong River, known as Lancang in China.

The Mekong Agreement followed the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes in 1992, known as the Water Convention.

“It was very complicated and took us almost 10 years to discuss [the agreement,]” said Keomany Luanglith, Laos’ Director of the Governance and Cooperation Division, during a side event.

“If we don’t have a cooperation mechanism, we will face water scarcity soon.”

Yumiko Yasuda, a transboundary water cooperation specialist at Global Water Partnership, emphasized in a panel discussion that more dialogue was needed to identify how to start new cooperation in Southeast Asia beyond the Mekong.

But the agreement on transboundary issues should also be translated into action at the local level to ensure its successful implementation, she suggested.

Louder voices

Perfecting transparency and the full participation of multi-stakeholders in the post-Mekong Agreement signing is still an ongoing process.

Riparian communities have long called the MRC to address “meaningful” public participation in development decisions.

They often reflected the gap through the public consultation process that led to the construction of hydropower dams on the mainstream Mekong, which have altered the water flow and affected fisheries and local livelihoods.

Before building the dams, the MRC member countries must implement a Procedures for Notification, Prior Consultation and Agreement, or PNPCA – a multi-stakeholders consultation process on the risks and mitigation plan of the projects.

The consultations were conducted for the commercially launched dams such as Xayaburi and Don Sahong, and planned dams such as Pak Beng, Pak Lay and Luang Prabang. All are located on the mainstream Mekong in Laos, the land-lock country that visions itself as the “battery of Asia.”

Consultations are also going on for the controversial Sanakham dam about two kilometers upstream from the Thai-Lao border. The project has been protested against by Thai riparian communities, which are concerned about the transboundary environmental impact.

“The MRC process involves the dialogues among national committees, focusing on ministers and governmental officials, but lacking the seats for local communities,” said Omboon Tipsuna, the leader of a community network in Thailand’s northeastern seven provinces bordering the Mekong River.

“It provides little space for the decision-makers to hear directly from us.”

She joined the MRC annual regional stakeholder forum in Vientiane last year when selected community representatives struggled to be involved in the conversations during the event, mainly due to language barriers as most panels were in English. There were booths displaying dam technology, with a small presence of the community’s knowledge and innovations.

“I felt like those gaining from the development have louder voices than ours in water management dialogues. The whole process allows them to take advantage of the Mekong River,” said Omboon, adding that she hoped the MRC would find ways to improve community engagement at the next forum on June 12.

The gap in public participation over the Mekong is closely linked to low political and press freedoms, as well as high corruption in the Mekong region. The 2022 report released by U4, an anti-corruption resource center, highlighted the Mekong water infrastructure as an area prone to corruption.

It identified three ‘hydro-corruption domains’ such as infrastructure development (hydropower, irrigation and climate change adaptation), direct exploitation (sand mining and fisheries), and resettlement and land rezoning along a water and land interface.

Infrastructure construction was the most common regional corrupt practice, according to the report.

Data sharing progress

To improve transparency and trust, the MRC has put efforts into improving the participation process and promoting water data sharing – one of the issues the commission brought to the Bali water forum.

MRC chief Anoulak stated that the member countries had agreed to share dam data with the MRC and would sign an agreement next month.

“The member countries have shared a lot of data already. This is an addition to that. They will share the dam data including dam inflow, storage and outflow, on all the mainstream dams and key tributaries for the first phase. If this works well and builds trust, then the next phase will involve more storage dams,” he said.

“Data or information sharing can build trust and transparency. But if they are misused, they can also erode trust, then the withdrawal of data.”

Data sharing with China is a work in progress, he added. At present, China shares hydrological data from two stations – the Jinhong and Ma’an dam, of which data is reported in real-time, daily, and available on the MRC website.

The MRC is hopeful that China will share dam operational data, which Anoulak believes will eventually happen.

On the other hand, Mekong representatives addressed a range of pressing water and climate challenges at the recent water forum.

Laos raised concerns over water scarcity and drought, which have recently disrupted the operation of hydropower dams, reduced crop yields and limited access to clean water.

Cambodia emphasized the impact of changing water levels in the Mekong River on water inflow to the Tonle Sap Lake, which millions of people rely on.

Thailand sought to enhance cooperation with China through a bilateral meeting aimed at discussing a new Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on water management. One of the provisions is China’s knowledge transfer on nature-based solutions.

“Managing water resources can’t be achieved with only either gray or green infrastructure. We need both,” said Surasri Kidtimonton, the Secretary-General of the Office of the National Water Resources and the Thai National Mekong Committee Secretariat, while joining the forum.

Green infrastructure includes natural and semi-natural systems such as wetlands, parks and forests that can enhance water availability and quality.

“We must admit that some specific investments in gray infrastructure may not work anymore because of hydrological change caused by climate change. We must also look toward sustainable solutions that work in the changing climate,” said Surasri.

This story was supported by Supporting Media Engagement on Water-Climate Issues in Lower Mekong led by Internews’ Earth Journalism network.