BALI, INDONESIA — Water is abundant and the world’s water crisis can be solved with technologies such as seawater desalination and solar power, claimed Elon Musk at the opening ceremony of the 2024 World Water Forum last week in Bali, Indonesia.

“Desalination, as most people know, has become very inexpensive. The availability of fresh water is simply about [a matter of] energy and transport,” Musk told government leaders, business executives and donors at the invitation-only event broadcast live on May 20.

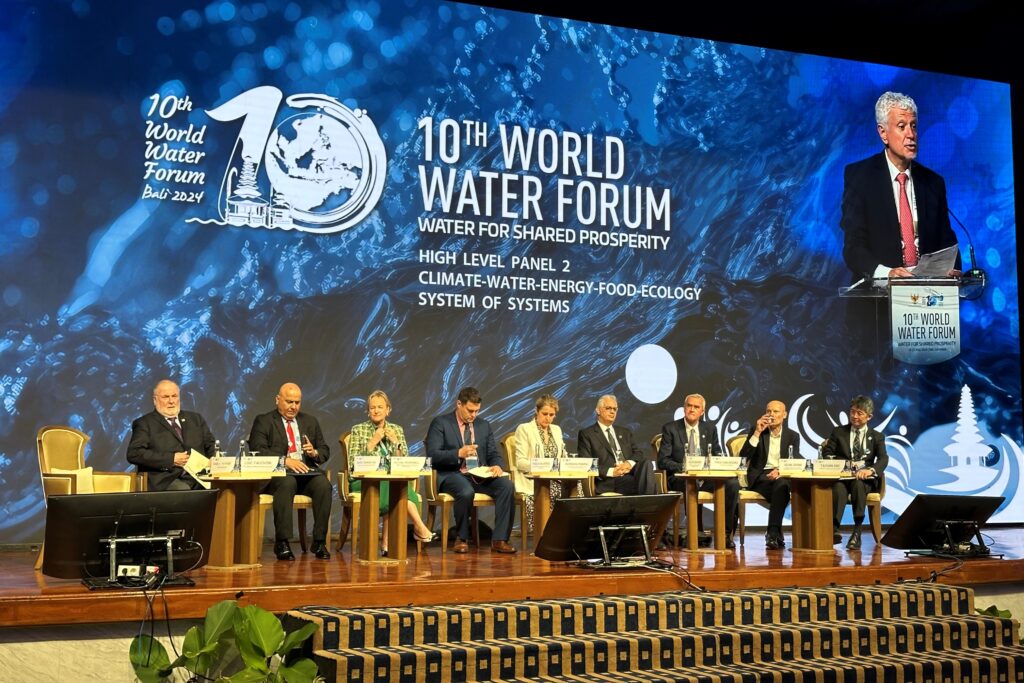

The forum spanned five days with more than 250 sessions discussing water security, management, governance, financing and innovations. Water scarcity, contrary to Musk’s claim, took center stage, yet his spotlight on technology echoed the forum’s overarching messages.

“To achieve this [water sobriety], let us put our trust in engineering and technology, combined with digital innovations,” Loic Fauchon, the President of the forum’s organizer, the World Water Council, told the audience at the opening ceremony.

“Thanks to them, we are ready to intensify ‘unconventional resources’ such as desalination, reuse of wastewater, construction of aquatic reserves, water transfers, careful use of groundwater and many others,” said Fauchon.

The World Water Forum is a gathering hosted every three years since 1997 by the World Water Council (WWC), a non-profit organization based in Marseilles, France.

Its 260 members include the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), UNESCO, UN Habitat, the Nature Conservancy, government bodies, utilities and infrastructure companies, academic and civil society organizations from OECD states and a few other countries like China, Morocco, Indonesia, Brazil and Peru.

This year, the forum boasted 50,000 participants from 160 countries, including those from the Mekong region. Forum sessions, however, were predominantly filled with speakers from WWC member organizations, as well as the forum’s donors such as the World Bank, water, oil and infrastructure corporations.

Technology was pushed as the key solution to the world’s water scarcity, from the forum’s expo floor to high-level panels and presentation sessions.

China and South Korea showcased their latest dam innovations and smart irrigation technologies using big data, artificial intelligence and cloud computing. International institutions like the FAO and World Bank stressed the need for digitalization in water management, such as drought tracking and irrigation monitoring.

Climate-smart, water-saving agriculture technologies were touted as triple wins for mitigation, adaptation and development.

Critics, however, said the focus on technology detracted attention from the actual limits of and competition for water on the ground, as well as the environmental and social implications of such technologies.

Seawater desalination, for example, is a highly energy-intensive process that produces a type of discharge called brine, which contains toxins like chlorin and copper and is saltier than seawater. Brine is often dumped directly into the sea, raising the salt level and depleting the oxygen, therefore harming life in the sea.

Climate-smart agricultural technologies save water and reduce GHG emissions, yet increase farmers’ dependence on organic fertilizers and perpetuate intensive monoculture, which have severely degraded soil across the world over the past decades.

“Efficient irrigation systems actually end up consuming more water,” Caroline Turner, Programme Manager for the FAO’s Asia Pacific Water Scarcity Program, told Mekong Eye on the sidelines of the forum.

“Because it’s a rational decision for farmers – they think if [they] can create more vegetables with less water, [they are] going to create double the amount of vegetables with the water [they] already had,” said Turner.

“It [technology] is not a solution. You can use all the technology in the world, but if you don’t limit the amount of water someone is allowed to use, they are just going to continue to use water,” Turner argued, hailing water allocation as a crucial solution to water scarcity.

Water allocation is a key aspect of transboundary water management, using policies and regulations to determine the economic, social and environmental values of water. Allocation regimes can be either market-based, administered systems or a combination of both.

At various forum sessions, including one high-level panel discussion on the systemic approach to food, water, climate and energy, calls to reassess the economic value of water were repeated.

“There are countries today around the world where energy is subsidized because you want water to remain socially affordable,” the World Bank’s Global Director of Water Saroj Jha told the audience. “It creates a very big fiscal problem for the countries, especially countries which have a low revenue base.

“Even the most sophisticated models that exist today have not been able to bring the fiscal and economic side of the system of systems, because it’s very complex modeling,” added Jha.

Activists from the global water justice movements, however, were deeply concerned about the privatization of water, corporate capture and the implications of market-based policies on marginalized communities.

“The accumulated evidence, however, overwhelmingly demonstrates that the market-based restructuring of the water sector exacerbates many of the pressing problems we are told it seeks to address,” read a statement from the People’s Water Forum, a parallel gathering to the Bali water forum organized by water activists over the past 20 years.

At the forum, marginalized voices were largely absent from most sessions, while events that bought together such voices were organized in silos without the presence of corporate and government leaders. Critics said that moving forward, inclusion was imperative to any water solution.

“It’s about humans, and it’s about the marginalized people that are getting left behind.” said Zahra Bolouri, Knowledge and Learning Manager of Water for Women at one of the forum’s synthesis sessions.

“It’s about the people who those pipes will go through their lands,” she added.

This story was supported by Supporting Media Engagement on Water-Climate Issues in Lower Mekong led by Internews’ Earth Journalism network.