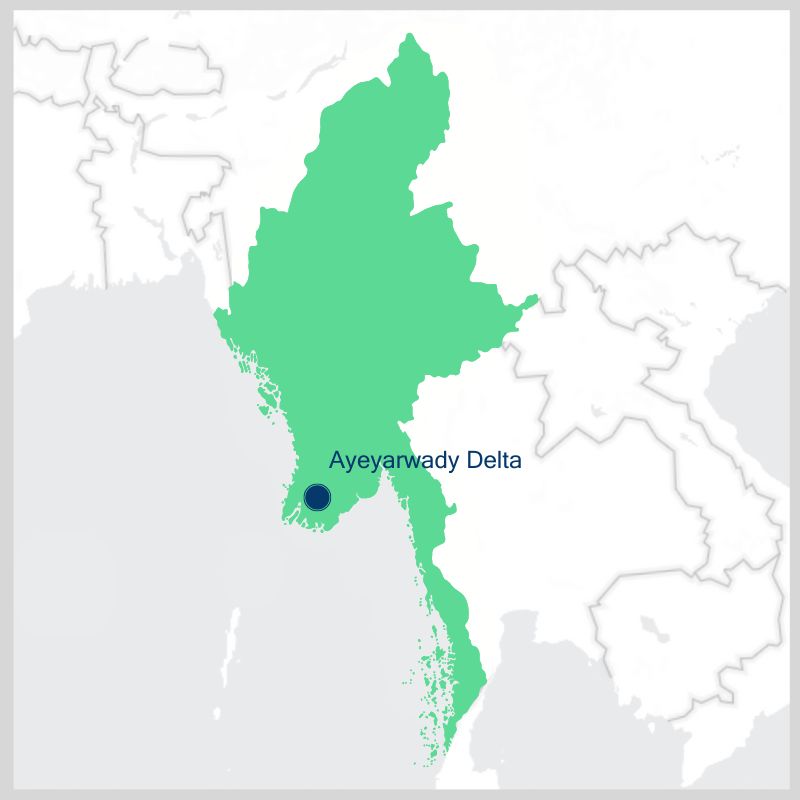

AYEYARWADY, MYANMAR – A coastal village in Myanmar’s Ayeyarwady Delta has seen its groundwater sources diminish drastically in the past decade, largely due to erosion caused by rising sea levels.

Win Htay, 45, looked at what was once an old water spring, now submerged under the sea beside Gawdu village in Myanmar’s Ayeyarwady Delta. It once provided her family with fresh water every day.

Within one decade, most of the springs and groundwater wells in her village have been either inundated by the sea or contaminated by saline water.

“We can’t find fresh water here anymore. We once had to walk a long way from the village center to the shore. The sea is right next to our houses now,” said Win Htay, who has lived in the village her whole life.

Gawdu sits at the southern tip of the low-lying Ayeyarwady Delta in Pyapon Township, with an elevation of 2.4 meters above the level of the Andaman Sea.

The residents settled in the area 80 years ago, starting with a few houses that eventually grew to 200. The village is now home to about 1,000 people, who mainly rely on fishing.

As the coast eroded, one-third of the 0.5-square-kilometer village became inundated permanently or seasonally, and there is a risk that more land will be lost to the sea in the coming years.

About 10 households, along with a monastery complex and school in the western part of the village, have been relocated to a nearby forest area, forcing them to cut down trees to make way for the new buildings.

Those lacking the resources to move out have been forced to seek temporary shelter elsewhere when the water rises, which happens at least three times a year, according to residents.

Apart from losing land and homes, finding fresh water has become a serious daily challenge for residents. As the amount of groundwater is shrinking, residents must wait for rainwater or buy water from other villages.

“In years with less rainfall, we suffer even more,” said 38-year-old resident Myo Min Hlaing.

Many are concerned that their village may become unliveable in the foreseeable future if no assistance arrives to help them cope with the water shortage.

Less groundwater

The World Wild Fund for Nature (WWF) released a report in 2017 on Myanmar’s climate risk estimates, which said the entire coast of Myanmar would experience between five and 13 centimeters of sea level rise from 2020 to 2029.

Sea levels may rise further from 20 to 41 centimeters from 2050 to 2059, according to the report. A sea level rise of only 0.5 meters would cause the coastlines of low-lying areas in Myanmar to recede by 10 kilometers.

The report highlighted that some parts of the country’s coastal areas may become permanently inundated or experience frequent flooding and erosion. This was evidenced during Cyclone Nargis in 2008 when many coastal settlements experienced devastating flooding and land loss to the sea.

Sea level rises, along with other climate impacts, including higher temperatures, have threatened groundwater in the Ayeyarwady Delta, according to a 2019 study by Myanmar’s groundwater expert.

Higher temperatures – as evident in the first half of this year when chronic drought, water shortages and heatwaves hit Myanmar and Southeast Asia – reduce the amount of groundwater being recharged, and results in more seawater intrusions in coastal areas.

The study suggested that less groundwater would be found in the coastal communities of the Ayeyarwady Delta, where 60-80% of households rely on groundwater for daily consumption.

To find fresh water, Gawdu residents must now travel half an hour by boat to nearby villages where they can buy fresh water.

They used to pay about 2,000 kyat (US$0.6) for a 300-liter bucket of water – the average amount used by a family in a day.

However, this price has doubled over the last three years due to rising fuel costs for water transportation. The cost of buying water now accounts for one-third of a household’s monthly income.

“Two boat operators are charging villagers to carry fresh water to their homes. If you order water in the morning, you will receive it around midday. But even with them, there is still not enough water for the whole village,” said Myo Min Hlaing.

That burden is usually placed on women’s shoulders, as they are the ones responsible for ensuring their families have water and food. Men, on the other hand, spend their time fishing in the ocean.

Aid rarely arrives

In a bid to solve the fresh water shortage, residents dug four wells in Gawdu, but only found salty water or very little fresh water that could be used.

“The water [from the wells] is slightly salty. It is not guaranteed that water will be sufficient and clean,” said Myo Min Hlaing. “I don’t think digging more wells will work anymore as it’s very costly and the results have been fruitless.”

Even purchased water from other villagers often turns salty, especially during the summer, as their groundwater sources are also infiltrated by seawater.

Independent researcher Kyaw Oo suggested the need for strategies from Myanmar authorities to improve residents’ capacities and resources to monitor and manage groundwater, so they can plan their water usage more effectively.

There is also a need to mitigate saline intrusion by relocating groundwater extraction sites to higher areas away from the sea and constructing coastal reservoirs that prevent saltwater infiltration, said the researcher.

The Ayeyarwaddy region is under the control of Myanmar’s military and there has been little presence of armed ethnic groups, making it relatively peaceful despite war breaking out across the country since the 2021 military coup.

However, the villagers rarely get any aid from authorities or external donors to help improve their quality of life.

“We received some water tanks from donations after the Nargis Cyclone more than 15 years ago. They were used to store rainwater,” said Myo Min Hlaing.

“But they are now delipidated as the water seeps through the tanks. Our financial situation doesn’t allow us to undertake the repairs ourselves. Only five families in the village can afford to buy new ones.”

Daw Ma Win Htay said she has always wanted Gawdu to have abundant fresh water.

“I haven’t been able to use the water much in my whole life. I wish I had more of it,” she said.

“Even if you do have money here, you can’t purchase water because it’s very scarce. We’re always struggling with water. It has created stress for the household.”

This story was produced with support from the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the Australian Water Partnership. It was first published in Burmese on DVB.