KAMPOT, CAMBODIA – Increasing cement production in a southern province of Cambodia is threatening karst landscapes, which conservationists seek to protect due to their unique biodiversity.

For the locals in the craggy, mountainous regions of Cambodia’s coastal province of Kampot, cement-making has chipped away at life – and the landscape as they knew it.

The area is home to a range of steep limestone peaks, known as karsts, that rise suddenly from the plains and are honeycombed with intricate cave systems.

These sharp formations are commonly found across Southeast Asia. But the cliff-sided mountains are somewhat unusual in Cambodia, where they make up part of a subgroup known as Mekong Delta karsts that stretch into southern Vietnam.

Renowned for the biodiversity they contain, these mountains are now under threat due to the proliferation of cement factories hungry for limestone, all to feed what the Cambodian government hopes will be a decade of booming infrastructure development.

Although Cambodia imports about 35% of its cement consumption, domestic companies such as Chip Mong Insee Cement – a subsidiary of the major development company Chip Mong Group, which is working in partnership with Thailand’s Siam City Cement Company – are now ramping up local production.

For now, this means blasting karst formations to get at their limestone, using heavy explosives to turn mountains into quarries.

Residents of Prey TaPreth village, in Kampot’s Sdach Kong Khang Lech commune, are neighbors to a major Chip Mong mining and cement factory site at Touk Meas Mountain and Roang Ses Mountain, with the capacity to produce 5,000 tons of cement per day.

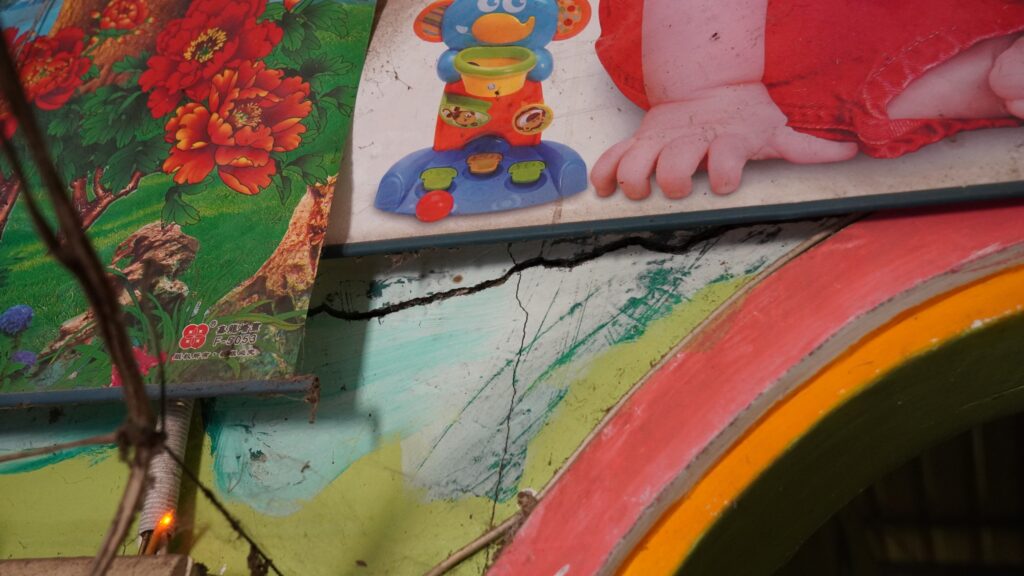

Many have experienced first-hand the knock-on effects of the country’s cement expansion. A woman who asked to go by the name Sopheap lives near the mining operation and said her home has been damaged by the shock waves of the explosive detonations used to extract limestone.

“I have fixed my house many times by myself. There is no compensation from the cement company,” she lamented.

As economic development goals put karsts under pressure for increased mining, local residents are not the only ones suffering.

Cambodia’s conservationists hope to preserve whatever they can of the nation’s karst ecosystems, describing them as a treasure trove of life.

“Karsts promote the evolution of species in those isolated environments in which new species evolve because they are so isolated from other similar environments,” explained Pablo Sinovas, country director of Fauna & Flora International (FFI).

“These species are unique. They are not from anywhere else in the world, they are from Cambodia. Cambodians should be proud of having these really high diversity areas within the country and hopefully spark some interest in their protection.”

Chip Mong Insee Cement has a partnership with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) for a biodiversity survey of a cement plant in Kampot, according to the IUCN’s 2021 annual report. It’s unclear to villagers what that means in practice.

Economic drivers

Kampot province hosts four of the country’s five operational cement factories, which are located on-site at limestone quarries.

Besides the Chip Mong cement plant, the other cement producers are Kampot Cement, Thai Boon Roong Cement and Chakrei Ting, plus Battambang Conch Chak in the western province of Battambang. These factories produced more than 10 million tons of cement in 2023.

A sixth additional cement factory is now under construction in Kampong Speu province, according to the industry group Cambodia Cement Association, to help ramp up domestic production to meet growing demand.

“We expect there will be an increasing amount of local cement usage when the government approves these projects,” said the association’s secretary-general, Puth Chandarit, though he did not provide an estimate of growth.

“We have enough raw material and limestone for the cement production that we can increase [output].”

This tracks with the country’s broader development goals. The semi-annual outlook of the World Bank released in late 2023 said Cambodia’s economic growth was projected to reach 5.8% in 2024 and 6.1% in 2025 due to anticipated infrastructure investments and benefits from regional trade agreements.

This means more cement will be needed locally.

Much of Cambodia’s drive for an infrastructure overhaul is connected to its relationship with China, a massive economic patron that has already invested billions of dollars into public works projects under the umbrella of its global Belt and Road Initiative.

According to Cambodian governance think-tank Future Forum, China is now the kingdom’s largest foreign investor, bilateral donor and source of foreign tourists, as well as its largest trading partner in terms of imports to Cambodia.

As of June 2021, China had built eight bridges and 3,287 kilometers of roads via more than US$3 billion in Chinese concessional loans.

Late last year, Cambodia initiated an ambitious 10-year master plan for public works prioritizing a list of 174 infrastructure projects.

Although the majority of these projects are road-related, the full plan covers a wide range from railways and logistics centers to airports and river transport schemes with the hopes of driving the economy into high-income status.

‘The hill is gone’

While Cambodia’s infrastructure systems are sorely in need of major upgrades, this development will come with environmental costs.

“In mountain areas, some resources can be extracted for use and some are needed to be preserved and protected for the young generation,” said Khvay Atitya, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Environment.

But even though karst mountains provide unique ecological benefits, these landscapes now have little to no protection in Cambodia.

Some sites have been registered as natural heritage sites, which provide little in the way of safeguarding, and none have been officially registered as protected areas.

Neil Furey, a conservation biologist who has worked extensively in Cambodia and elsewhere in the region studying caves, said karst environments are not well understood in the kingdom.

“If you go across the border, go north to Laos, east and north to Vietnam, limestone karsts are among the most important protected areas in those countries,” Furey said.

The opposite is true in Cambodia because until very recently, not one karst in the kingdom was nationally protected for its biodiversity. The destructive effects of mining, he added, are typically irreversible.

“Cement mining in general completely removes the ecosystem, so when the quarry is finished, the hill is gone – there is no hill, the ecosystem is lost and you can’t replace it,” Furey said.

“Anything that depends on that ecosystem or lives in that place is simply gone.”

Local concerns

The loss of craggy karst peaks also stands to impact human neighbors. Many of the remaining mountains attract tourists and religious visitors, all of whom help to generate income for local communities.

In the case of the Chip Mong Cement site, limestone mining has also triggered land-use conflicts with neighboring villagers.

Villagers at Prey TaPreth said plant representatives had promised trickle-down economic benefits if locals sold their land to help the factory build a new road to connect its operations to a nearby national road.

“If you have an umbrella, you can sell coconuts and water to make a living easily along the road,” some of the villagers recalled to a journalist, paraphrasing Chip Mong representatives.

But it wasn’t as simple as that. The villagers now claim the cement maker broke its promise by fencing off its new road, leaving no chance for any businesses to grow, nor allowing any traffic access except for cement factory trucks.

They added that the company even built a gate controlling access to a public road, requiring villagers to ask permission from a security post to cross.

Local villager Sopheap, whose home was damaged by shocks from explosions, said she and her husband had built their house with a bank loan of $10,000 in the expectation the road would be a source of income.

Now, they have to rely on one of their children who migrated to work in South Korea to repay the debt.

Entry to the mountain is now prohibited. Villagers claim the company has never listened to their concerns.

“The factory’s security guards open the fence and allow us across. We have the right to go only north and south. We can’t go east or west. And if we cross their road often, they are not happy about it. They complain that we cross their road too much,” she said.

Chip Mong Insee Cement’s public relations manager Vichea Sopheak Tieng did not respond to requests for comment.

But he told Dialogue Earth back in 2020 that staff regularly meet with community leaders living near their factory to assess the environmental and social impacts. The company also has a rehabilitation plan to be implemented after their concession.

The website of Chip Mong Insee Cement includes a big section on “sustainable development,” which says it has committed to “sustainable development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Environment Ministry spokesman Atitya encouraged villagers affected by the cement plant to file complaints with authorities. But villagers said they’ve already lodged complaints with their local officials – who in turn told a journalist that the issues are already resolved.

Banteay Meas district governor Nou Chanda, who has been in office for more than one year, said he believed the issue at Prey TaPreth village was cleared by his predecessor.

He added that villagers should call or meet him if they still had concerns, but went on to deliver broad praise for Chip Mong, one of the country’s largest companies.

“Among all factories, there is only Chip Mong which helped to develop the country. To be honest, I admire them for their work, for helping to develop many things,” Chanda said.

“They helped to build many kilometers of canal, helped to develop the district and the living standards of people. The company should be encouraged and praised for its commitment to helping our economy and nation.”

But villagers at Prey TaPreth still have issues with the neighboring plant. A woman who asked to be quoted by the name Sreymom, for fear of potential loss of livelihood, said her husband was employed at the cement factory, but added their standard of living had not improved at all.

Despite her husband earning about $400 per month, she claimed the factory had caused many issues since its arrival.

“In the past, we could store rainwater to drink, but because of dust from the cement production, we have to buy bottled water and underground water as rain is no longer safe,” Sreymom said, alleging that dust has also caused respiratory health issues that had not been seen before in the village.

Local health officials drew issue with that, even as they acknowledged the plant does impact the environment.

“I have checked data and reports from health centers in many communes in the area, and there are no increases in respiratory health issues,” said Kampong Trach operational health district director Khaeng Saravuth.

The push for more protection

Among local controversies, the environmental impacts of increased limestone mining still loom in the background. Conservationists such as Furey say the environmental value of karst mountains can still coexist with industry.

“Now is the time that we need data, surveys and evidence to identify which karst areas are important for biodiversity so that some can be allocated to local communities and some can be set aside for cement production,” he said.

“Some hills are already damaged, but others are still in good condition for biodiversity, so we should protect those.”

Sinovas, of FFI, said his organization and others were working toward the same goal of winning official protections for karst landscapes.

In early 2021, a governmental sub-decree listed some karst mountains and a related cave system as natural heritage sites in Kampot province.

An attached photo in the sub-decree showed some parts of a mountain had already been damaged by the Kampot Cement factory, which started its operations in 2008.

“When karsts are not protected and managed appropriately, the threat is that limestone will be quarried unsustainably, which could wipe out species that we haven’t discovered yet,” Sinovas said.

“Humanity might never know about certain species in karsts because they could be extinct before we even find out.”

This story was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.