STUNG TRENG, CAMBODIA – An economic land concession granted in 2018 has failed to deliver development and prosperity to local communities, who now face an uncertain fate after being ordered by authorities to vacate their houses and leave their land.

Beyond a high barricade, a few dozen workers were seen stripping insulation from the skeletal frame of an abandoned warehouse.

Not far away were dilapidated housing units once used by workers. Their metal walls and roofs corroding, with doors left hanging open.

Guards, who claimed they were hired after the landowner left Cambodia, were keeping watch over the property.

Situated within an economic land concession in Cambodia’s northern Stung Treng province, these remnants of buildings and the surrounding farm were once owned by a Chinese company called Siemon.

A resident who visited the area to purchase used construction materials for his own business said the land was once used to grow and sell watermelons. However, the operation failed after two or three years.

“In the contract, this land was supposed to belong to the company for 45 years,” he said. “After they stopped, they might have returned it to the government.”

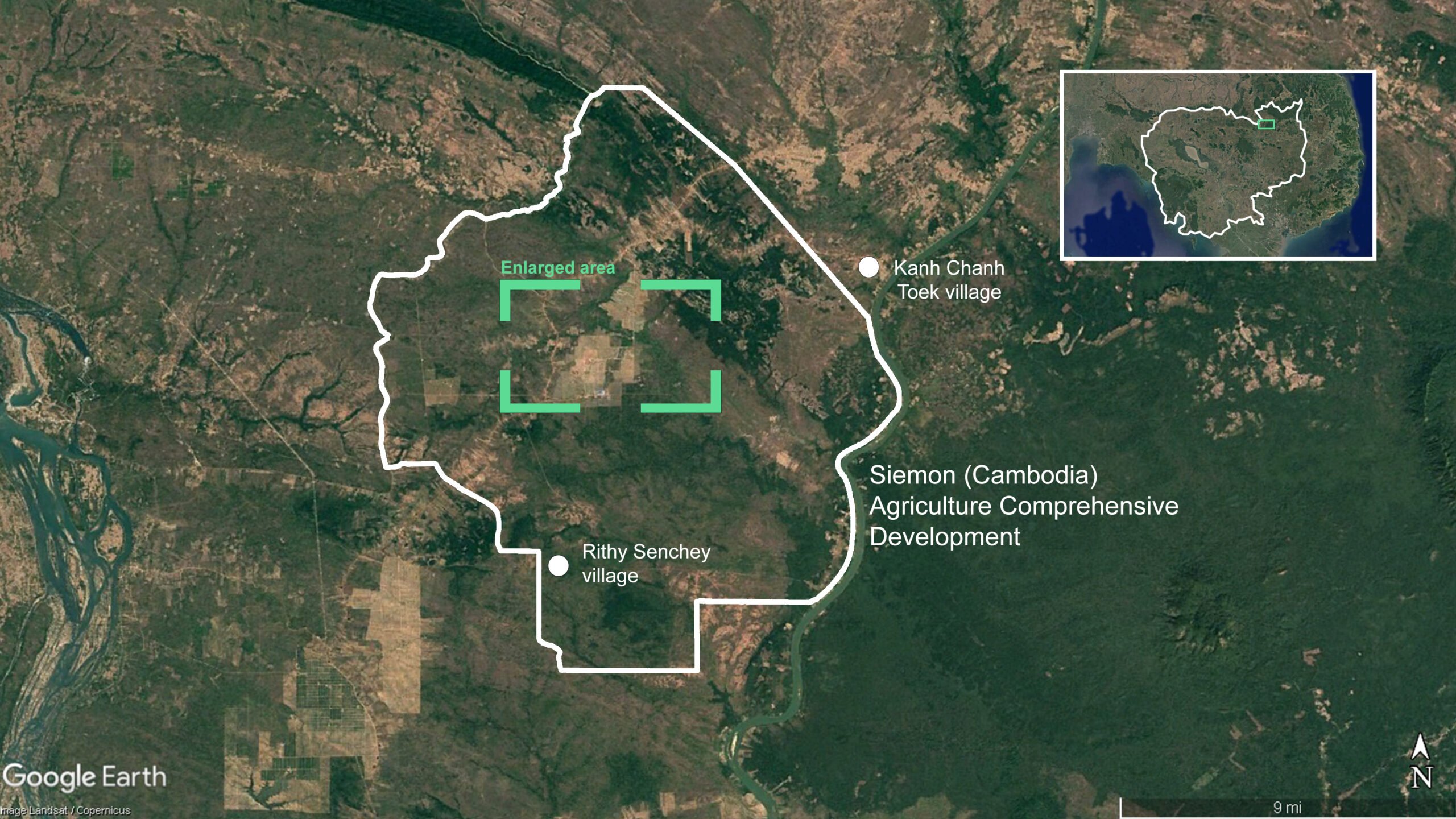

Siemon was originally granted the concession in 2018 as part of a US$200 million project to ‘replant’ approximately 27,000 hectares of degraded forest, which had previously been cleared by Green Sea Agriculture – a company owned by local tycoon Mong Reththy, who is also a former member of the Senate and a close counselor to former Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Local media reported that Siemon planned to plant fast-growing trees like acacia and eucalyptus, raising environmentalists’ concerns about further deforestation to make way for these non-native commercial species.

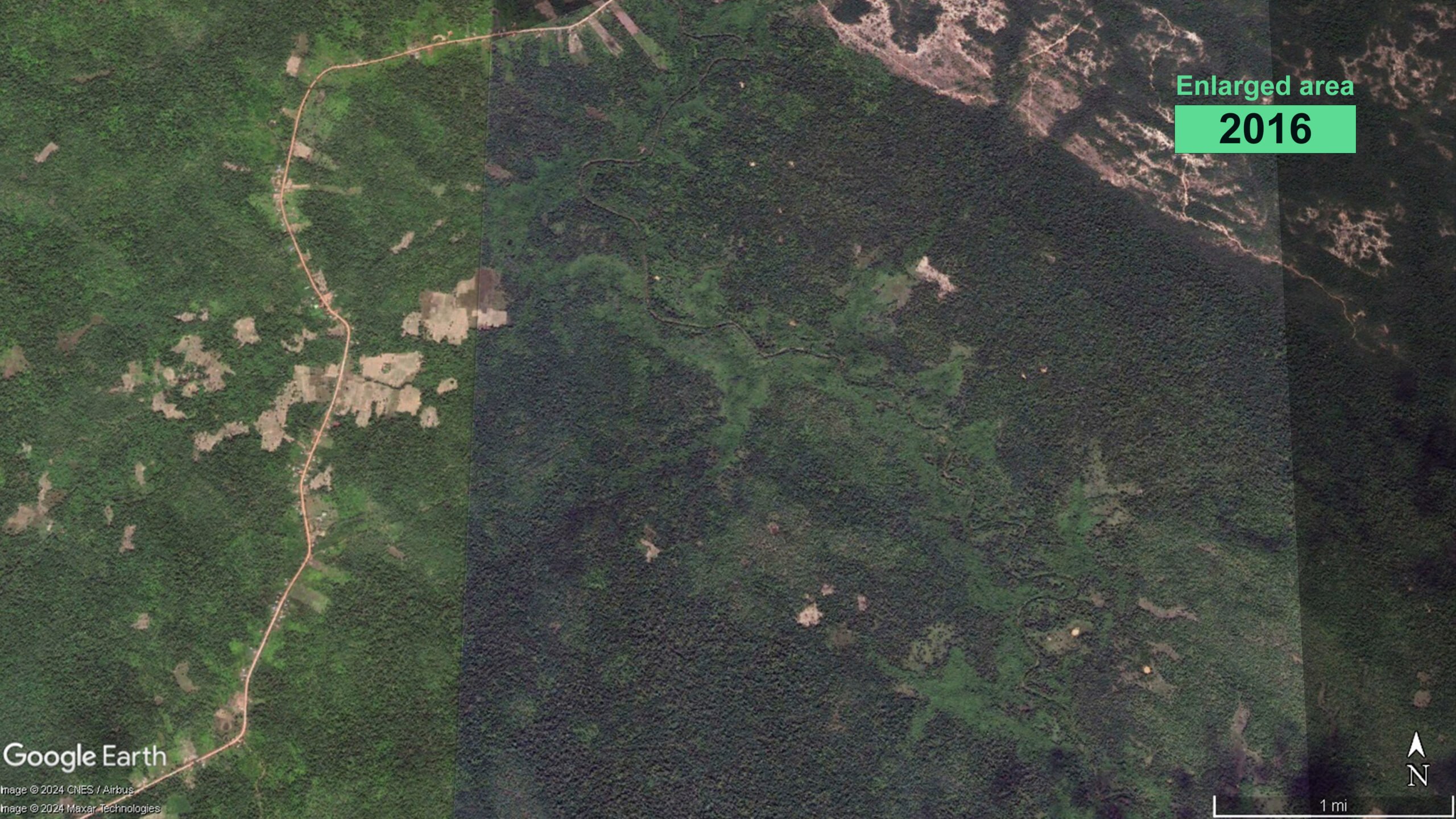

However, recent satellite imagery showed that only 7% of the project area had been developed, with a network of roads forming a chessboard pattern for a plantation. Reporters found no evidence of tree plantations near the warehouse.

While the project’s questionable outcome and the company’s absence remain unresolved, Cambodian authorities are now preparing to evict nearby residents who are allegedly encroaching on company land.

Fail to deliver prosperity

About nine kilometers south of Siemon’s farming area, residents in Rithy Senchey village have received eviction notices marked in red spray paint on their front walls, declaring they must leave by the end of June.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries also issued a letter on June 7, warning that families across Siem Pang and Borei O’Svay districts – including Rithy Senchey village – would need to demolish their homes and vacate the area.

The letter labeled the occupants as “criminals” who had taken “anarchic” actions by occupying the land.

Kum Yi, 47, and her husband purchased four hectares of land in Rithy Senchey village for $6,000 about three years ago, and they invested another $8,000 to clear the land for cassava farming.

“We don’t know where to go. We have four children, and we spent everything to grow here,” she said, adding that the eviction notice arrived only one week after they had planted their crop.

Less than two weeks before the planned eviction, Pann Khem Bunthon, the deputy-director of Prime Minister Hun Manet’s cabinet, visited Rithy Senchey and urged residents to remain calm and assured them that officials would find a solution.

The cabinet members returned a few days after the June deadline to inform residents that they could stay for another seven months. Bunthon visited again in mid-August, but still without a solution for the villagers.

This situation has sparked confusion and fear among the villagers, who are not alone in facing eviction and uncertainty after the granting of economic land concessions (ELCs).

ELCs are long-term leases granted by the Cambodian government to local and foreign investors for the development of industrial agriculture, officially aimed at generating significant revenue and creating jobs. Other activities under ELCs include mining, port development and reforestation projects.

Since the program started in 1996, more than 2.2 million hectares of ELCs have been granted to over 300 companies, according to the rights group Licadho.

However, most of these ELCs have failed to deliver prosperity and have instead led to widespread deforestation and land disputes across the nation.

In response to the surge in land-use conflicts and the lack of promised revenue, former Prime Minister Hun Sen signed a moratorium on the granting of new ELCs in 2012. However, the government has continued to issue land leases, often in forested areas and involving powerful tycoons with close ties to the government.

In Siemon’s case, reports suggested that this little-known company was involved in logging before it abandoned the area.

Forest preservation activists uncovered a letter from August 2019 that allowed Siemon to export timber from Siem Pang district, where it held a land lease, through Snuol district in Kratie province to Vietnam. The letter was signed by the deputy director of Stung Treng’s Agriculture and Forestry department.

Satellite data on forest loss from the University of Maryland indicated significant logging activity, particularly between 2016 and 2019, in the same area where Siemon’s warehouse and roads are located.

The trade database Trademo also identified that Siemon exported at least $4.6 million worth of timber, with most of the trade occurring in 2021.

Dispute over land ownership

Stung Treng’s provincial spokesperson, Men Kung, did not clarify the status of the Siemon concession, stating only that the area was state land and the government “may consider granting economic land concessions to other companies.”

He justified the eviction by explaining that some companies take longer to develop their businesses, and therefore residents should not have moved onto the land.

“For some companies’ projects, we can see [development] immediately, some companies’ projects take a long time. I do not mean to encourage people to encroach on state land, and they should show loyalty to the government,” he said.

A resident of Kanh Chan Toek village, which was listed in the eviction notice, disputed the government’s claim that he was occupying land the government would lease.

He pointed out that there was evidence of people living there before any company licenses were granted. He showed a document from 2012, provided by student surveyors asserting his occupation of the land before Siemon’s presence in his area.

Several other residents in Kanh Chan Toek and Rithy Senchey villages held similar documents, proving they had lived on the land for decades.

To bring residents across the country into the land titling system and identify land use, then-Prime Minister Hun Sen had ordered thousands of student volunteers to measure and mark the land.

“There’s no rational reason for them to take our land because I used to grow there and I have a land title [with local officials], so if they are going to take my land, I will be protesting,” he said while asking to remain anonymous out of fear of repercussions.

Phon Thon, the 70-year-old village chief, estimated that about 70 families in Kanh Chan Toek village had land within the eviction site, but it was mostly farmland for rice, cashews and other crops to support the families.

He hadn’t heard if officials would be willing to negotiate compensation for residents’ land, but he said it seemed as if the eviction was not happening immediately in his village.

Villagers refuse to leave

Back in Rithy Senchey village, residents gathered at a drink shop in the balmy June afternoon. They told reporters that the day before, they had met at the same shop to strategize how to protect their land.

Resident Bun Somath, 52, said the long-staying community had been dragged through land disputes before the arrival of Siemon.

The same land was previously granted to Green Sea Agriculture, a company owned by powerful tycoon Mong Reththy.

However, the residents managed to negotiate an agreement with the tycoon, allowing them to stay. Later, Reththy gifted the land to them, creating a village renamed Rithy Senchey.

Reporters found a 2014 sub-decree, which indicated the company cut some 2,400 hectares of land in Siem Pang district and distributed it to 842 families.

When asked if he would be willing to negotiate in the latest eviction notice, Somath said he and others wanted nothing but their land where it is.

“I believe the prime minister won’t make us disappointed, but if anything happens, we won’t agree and we’ll still live there, we won’t leave.”

This story was first published on Kiripost, and edited by the Mekong Eye Team. This story was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.